BY: ANNABELLE LATZ

North Canterbury beef farmers Stu Loe and Andy Gardner are not seeking sympathy, but they do want to highlight the inadequacies around the Mycoplasma bovis testing systems.

Stu farms beef and dairy beef heifers and steers, Andy finishes Friesian bulls, and they have each had two encounters with M bovis on their farms.

They say the timeline around results and methods of slaughtering and remuneration left them frustrated.

Andy received a call in May 2018 from the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) that he had “animals of interest” on his farm that required testing.

A representative from AsureQuality visited the farm and ran blood tests on a sample of 120 of the herd and nasal swabbed 80% of that sample.

Andy was complimentary of the work carried out.

He learned there were a dozen bulls to be slaughtered, which he accepted and received remuneration for, but it was the timeframe and administration around this whole process that caused the frustration.

“The laboratories couldn’t keep up with the testing demand and we had to wait five weeks for a result. In the meantime, the animals were in lockdown.”

After five weeks, Andy learned that one “animal of interest” was to be slaughtered to confirm whether or not his farm had an M bovis case.

He said another area lacking in this whole process was ensuring there was the necessary killing space at the meat works.

“We were participants carrying out this system. It should have been easy, but it wasn’t.”

The weeks went by, the beast remained, and the clarity around whether or not his farm had a case of M bovis was no clearer.

He was told by MPI the reason for the holdup was that there was neither the transport nor the facility available to get the bull slaughtered.

It took three months from receiving notification of slaughter to the bull being slaughtered, and it would have been longer if Andy had not instigated action.

“The human cost of that is immense. It starts to weigh you down.”

THEY, NOT MPI, HAD IT SHOT

In the end Andy got sick of waiting, so he asked for the animal to be shot on his farm.

In the end Andy got sick of waiting, so he asked for the animal to be shot on his farm.

“That was a way to put a line under it and move on. It shouldn’t have happened this way.”

This took three requests, after which his case manager from AsureQuality visited his farm, was present for the slaughtering of the 15-month-old Friesian R2 bull, and then carried out the testing on the tonsils.

The test result came back negative – Andy had no cases of M bovis on his farm.

“But they shouldn’t have animals of interest waiting around for that long.”

His second taste of this system was in October 2019, after a line of 42 bulls he bought from Geraldine were animals of interest. They were isolated from his other bulls the entire time, and after a month’s wait for the results he was informed by MPI they were to be slaughtered.

“The issue around this was the compensation,” Andy says, explaining what happened that summer.

In order for the notice of direction (NOD) to be lifted, a census had to be carried out where all the bulls on his farm had to have their tags read and recorded.

Meanwhile he had learned he was able to claim reimbursement for hired labour, bikes, dogs, and yards wear and tear. But he was also not able to invoice for his own time, or lost opportunity costs as a result of his being pulled away from other farm work.

“They don’t build goodwill.”

It was a fairly big job getting in 617 animals, especially in the height of summer as it was pencilled in for mid-January 2020.

The process took two days but he was only able to claim for one day, which he only learned about when he put through his claims and this particular one day was rejected.

“I should have employed two guys, they expect me to work for nothing.”

It’s the gap between who makes the rules and who has to follow them that is a major problem.

“How can you make such an arbitrary rule from Wellington? I think there is a massive disconnect in Wellington between what they think happens and what actually happens…there shouldn’t be a blanket approach.”

Although very frustrated, Andy weighed it up with the news he received 12 days later that there were no positive tests, which meant he could sell what he wanted to.

He wanted to put it all behind him.

“It was all bloody unpleasant. I just wanted to make it go away, to put a line under it and put it behind me.”

JUST A FARM OF INTEREST

Stu learned he had 21 animals of interest in April 2019, and the AsureQuality team visited his farm to run blood samples on his herd of 250.

A couple of weeks later the test results showed 21 had to be slaughtered for further testing, but all results showed up as negative.

“We realised we were just farms of interest, we didn’t have it.”

This happened in June, the slaughter price falling just short of the value price so MPI made up the difference.

Stu was complimentary of Rural Support, an organisation installed within the programme to be a sounding board and support system for farmers.

“They gave me a ring, they were just good to vent to if nothing else.”

To relieve himself of the NOD, Stu was required to do a whole-herd census.

He was expecting the all clear, but in fact a further 12 had to be slaughtered.

Again, no positive cases.

Stu said difficulty lay in the fact not all meat works were set up with the testing infrastructure to accept animals related to M bovis. So this small number was sent to a dog food company in Timaru in September, which didn’t pay Stu itself because the animals were deemed “worthless.”

Although he wasn’t out of pocket because he received reimbursement, he later learned the meat was processed and sold as pet food.

He said more research needs to be done on these details, given we’re all taxpayers.

“So some people are doing really well out of this. And money is just being thrown around.”

And he only found this out because he had to chase MPI for the tracing paperwork so the animals could be taken off his farm system.

“They couldn’t tell me what animals had gone there, because their NAIT tags hadn’t been checked against what went onto the truck when I wanted them.”

The confusion was a concern.

“These were animals of interest, the ultimate test was failed by the place MPI asked me to send them to.”

Between his two cases life was still busy on the farm with lambing and all the day to day happenings of farm life.

To mitigate this frustration, Stu was able to be reimbursed for his time and any external labour he used for the M bovis testing requirements.

“We are just highlighting the fact it was a shit situation, made worse by shit administration. It’s okay for the younger dairy farmers who are more used to dealing with government departments, but for the sheep and beef farmers this can be really difficult.”

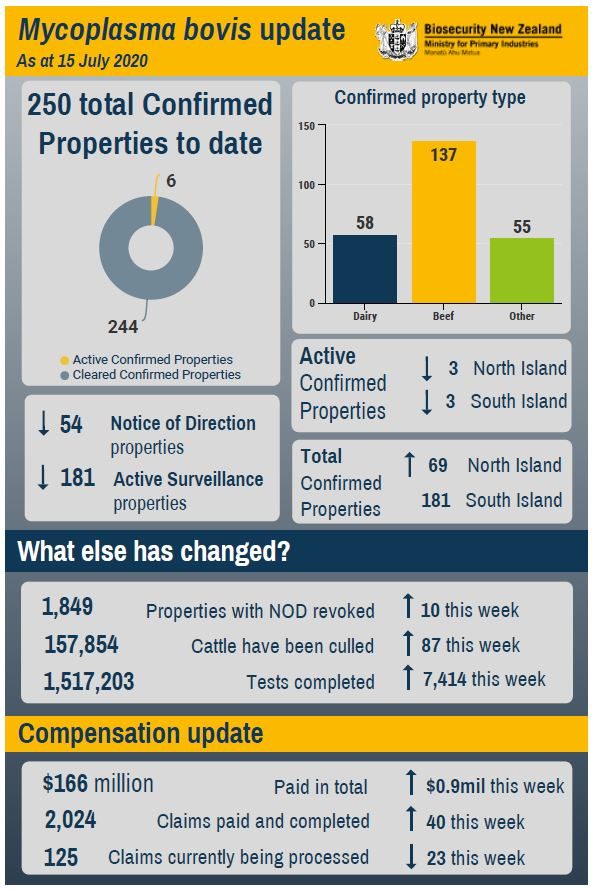

Overall, progress towards eradicating M bovis is tracking well, according to M bovis Programme Director Stuart Anderson.

He says the first few years were tough and hard going, but case numbers are steadily dropping ahead of bulk tank milk starting up again in spring, along with calving.

Recent months have created big challenges with the drought and then Covid-19.

He said the programme’s model of identifying the farms, contacting the farmers, testing and providing support is a ‘step by step’ process, and they are always looking at ways to improve their systems.

“We have all learned a lot, and we always welcome feedback. There is still more to do, we need to keep pushing on.”