Failing drenches, labour shortages, and consumer preference for minimal chemical inputs are why a low input sheep progeny test is essential for the future of the New Zealand industry, says a South Canterbury farmer. Andrew Swallow reports.

Attempting to finish lambs after weaning without drenches, and mostly on grass, sounds like a recipe for disaster, but a major project in South Canterbury shows it can be done.

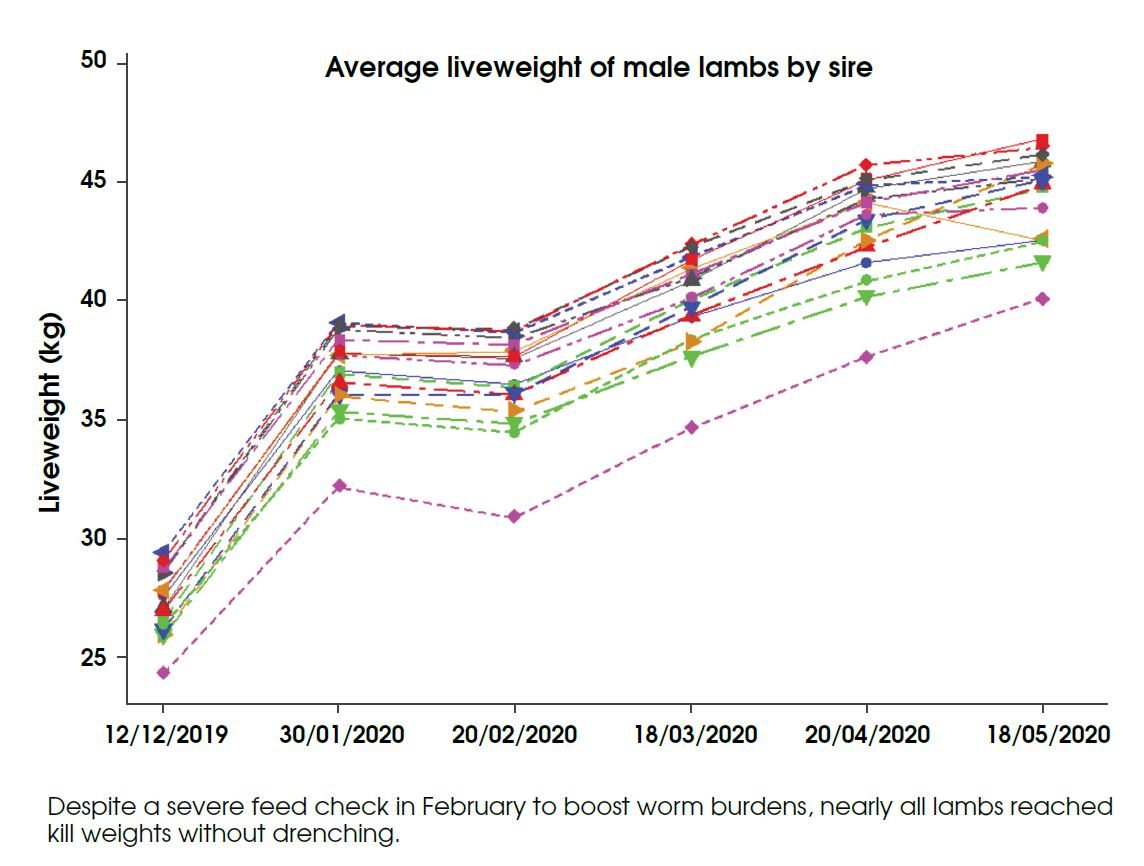

Of 450 male lambs produced in the first year of the test, all but 20 were fit for slaughter by mid-May, and many well before that. Ewe lambs, retained for further assessments, demonstrated similar weight gains.

In the case of males, the overall growth rates were achieved despite going backwards for three weeks in February. This was when they were forced to graze paddocks to golf-green level in order to increase the worm challenge and hopefully tease out differences in genetic ability to cope.

These were findings from the Beef + Lamb New Zealand (B+LNZ) Genetics low input sheep progeny test (LISPT).

The lambs were from artificial insemination of 1000 commercial ewes at Orari Gorge Station, inland of Geraldine, with 17 rams from 15 stud flocks across the country.

They were mostly from breeders focusing on disease and worm resistance and animal welfare as well as the usual growth and carcase quality traits, but a few were from out-and-out production-focused studs. Breeds included pure-bred Romney, Perendale, Coopworth, Finn and Wiltshire, and a range of maternal and terminal composites.

Scanning revealed 70% in lamb, which host farmer Robert Peacock said he was happy given the use of AI, and 920 lambs resulted. At tailing, leg and tail length and area of bare skin at the breech were measured. Only ewe lambs were docked: males were made cryptorchids but kept their tails in light of concerns tailing might become a negative for some markets.

Tail length ranged 15 to 32cm, averaging 23.7cm, with lambs sired by Finn and Texel-based composites having the shortest tails; Perendale, Coopworth and Wiltshire-sired lambs the longest.

Progeny of the Wiltshire sire had the largest bare-breech area, closely followed by a three-quarter Romney.

At weaning, December 12, all lambs were dipped and drenched with a triple, and males crutched to provide an equal start to the trial thereafter, even though only 5% were dirty. A control mob of 20 late-born twin lambs from Orari’s commercial Romneys was added to the males.

Male and female mobs were then turned out on to lambing paddocks to ensure they faced a worm challenge. However, by February the faecal egg count (FEC) of the males was averaging only 463, hence the decision to graze harder to raise the burden.

Average FEC of the ewe lambs was already 1615 although some had nil and others over 2000, demonstrating the range of parasite resistance among them, notes Peacock.

By the second FEC timing, in May, the tables were reversed, the males’ FEC averaging 2500 but females’ 750.

“Females develop their immune system earlier than males so that was probably starting to kick-in to reduce that worm burden.”

In May there were still some lambs returning nil FEC results, which, given the challenge they’d faced, was “pretty impressive,” he added.

CONTROL LAMBS DRENCHED

Several rams’ progeny, notably a Romney and a couple of Coopworths, had markedly lower FEC scores, but two Romney rams were also among the bottom three. The project report notes some rams were from flocks not selecting for parasite resistance.

Besides FEC assessments post weaning, males were yarded, weighed and scored for dags roughly every four weeks thereafter, with the control lambs drenched at each yarding.

Despite those drenches, mean weight of the control mob in May was still about 2kg less than the trial mob, having started out at 5kg lighter.

“The growth rate of the control and the trial lambs wasn’t that different,” observes Peacock.

Dags were scored at weaning (Dec 12) and in February (females Feb 10, males Feb 18). Despite the males having tails, “there wasn’t a big difference between the girls and the boys.”

Mean score for females and males rose between the two timings, from 0.61 to 1.53 for the females and 0.88 to 2.00 for the males, but within that there were still “plenty with zero dags right through into May, probably about 20%, and 20 or 30% were just ones or twos.”

In line with the project report’s note that dagginess isn’t strongly correlated with FEC, some rams’ progeny with the best mean FEC results had the worst dag scores, and vice versa.

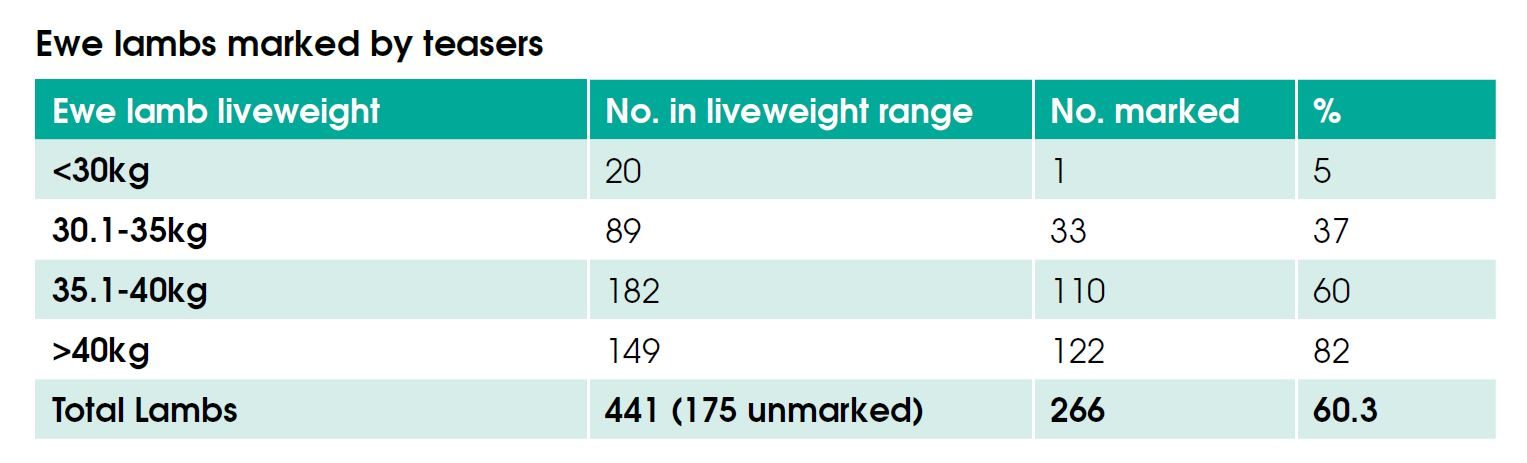

Ewe lambs were shorn in March, which took about 2kg off them, then run with teasers in May. When the teasers were removed, on May 27, average liveweight was 38kg but many lighter lambs had still been marked (see table).

“It was a good example of why you shouldn’t let the ram decide which girls are ready to lamb as hoggets. It’s going to end in trouble!”

There were substantial differences in onset of oestrus among the lambs. Only 19% of one Romney ram’s progeny were marked, despite their liveweight being in line with the mean, while 100% of a three-quarter Texel/quarter Perendale sire’s daughters were marked. With a mean of just under 39kg the TexPer ram’s progeny “weren’t the heaviest either,” noted Peacock, that accolade going to a Romney sire’s daughters.

While not formally recorded, and despite males being cryptorchids, sexual activity also appeared sire- or, more likely, breed-related in the male lamb mobs. The progeny of Finn or Finn-cross rams, in particular, spent more time fighting with their counterparts towards the end of the trial, which probably affected growth rates. However, most of those lambs would have already been killed under non-trial circumstances.

“We would have liked to have two kill dates but, for the purposes of the test, one later kill date was decided on so that we could collect as much data as possible.”

Due to the practicalities of booking works space with BLG staff on hand to record test data, the kill date has to be booked months in advance, he points out. One of the main changes for the coming year’s work will be a March kill date.

“If we bring it forward it will be more realistic, but not all the sires in the test have been chosen for high growth – they’re in there for other reasons,” he notes.

The 400 or so ewe lambs from last year’s drop will be divided into sire groups as hoggets, then a few from each group will be allocated to all sires in the test, except their own if still participating, for insemination.

Mothering ability and lamb survival will be monitored, in addition to other test traits.

In the meantime, 10 daughters of each sire have been at AgResearch for feed efficiency and methane emission measurements. While full data on that work are still to be analysed and released, Peacock said he’d just heard they’d put on 320g/day over eight weeks to average 56kg by the start of September.

TEST SHOWS VALUE OF HIGH-PROTEIN PASTURE

One aspect of feeding that the test’s already highlighted is the value of high protein pasture such as pure clover.

After slowing the rotation of male lambs on traditional ryegrass-clover paddocks in February to raise the worm burden, once he was confident that had been achieved, and because lambs were losing weight, Peacock temporarily put them on to pure stands of red clover to recover.

“In three or four days they looked like different sheep,” he recalls.

Without a drench, growth resumed and by slaughter the mean growth rate from weaning to May 18 was more than 100g/day.

“These lambs faced a significant worm challenge and they were still growing quite well: 100g/day may not sound very exciting but it’s about the national average, and nationally most lambs are drenched regularly, so this shows it can be done without drenches.”

The best growth lambs were sired by a 3/4 Romney, closely followed by a Finn and a Coopworth. The Coopworth’s male progeny also had the third lowest FEC scores, but the Romney with the lowest FEC scores was also the lowest for growth.

Peacock warns against reading too much into any one breed or ram’s individual performance in the test’s first-year results, or extrapolating those to form a general judgement about the supplier stud’s genetics, because the rams were supplied as reference sires. Rather, potential ram buyers should look at the Sheep Improvement Ltd (SIL) data for rams they’re interested in, and whether the stud is part of the LISPT as all data from the test will go into SIL.

“For me the biggest thing overall is how well they all coped without drenches. We live in a summer safe rainfall area, and with that comes plenty of worms.”

Having commercial Orari Gorge ewes as mothers, which have long been selected for worm resistance (see Project Background), would have helped, he acknowledges. For farmers seeking to reduce drench dependence in their own flocks he suggests a staged approach.

“Be careful not to do too much, too fast. Maybe move your drench interval out by a week or two, and don’t cull as many ewe lambs at weaning… you need to give them a chance for their immune system to develop so you can select those that can cope with a worm challenge, as well as all your other normal selection criteria.

“This isn’t a silver bullet and it’s quite a slow process to breed worm resistance into your flock.”

*Webinar available on YouTube. Search Low Input Progeny Test. Fast forward to 5mins 40secs to skip the intro.

LOW INPUT TEST –A NORTH ISLAND PERSPECTIVE

It doesn’t matter whether you’re farming in the North or South Island: the Low Input Sheep Progeny Test will help the industry breed sheep that are more profitable in future, says West Waikato breeder Kate Broadbent, one of six farmers on the test steering committee.

“The industry as a whole has to be able to reduce inputs, especially drenches and labour,” she told Country-Wide.

“When lambs are making $9/kg we don’t mind too much putting the time in to dag and drench lambs, but if it drops to $4/kg, ewe numbers are going to plummet again.”

But that exodus might not happen if farmers have flocks of ewes capable of weaning their own weight in lambs without a drench or a dag, she argues. First-year results of the test suggest that is possible if the right genetics are combined with smart management.

“I think we were all pleasantly surprised with how well the lambs grew. They weren’t the fastest but it demonstrated what we can do with absolutely minimal drenches. It shows that commercially maybe only one or two drenches could be adequate instead of every 28 days. A good percentage of these lambs’ tails were still clean.”

Besides demonstrating what’s possible and identifying genetics to select from, the test is also providing good links between sires, so breeders involved can assess performance of home flocks relative to others.

However, like Peacock, Broadbent stresses that the sires in the test are just reference sires, so producers shouldn’t judge the supplying stud flock on the reference sire’s performance in the test.

An interesting feature of the test for the coming year will be what rams to inseminate the first year’s ewe lambs with when they return from AgResearch’s methane work.

“It’s a real fruit salad of hoggets we have there now, from Finns to Texel and everything in between.”

Long-term she’d like to see a parallel North Island test set up so rams could also be assessed for location specific problems such as facial eczema and barbers’ pole (Haemonchus spp) worms.

PROJECT BACKGROUND

The concept for the Low Input Sheep Progeny Test came from discussions with like-minded breeders and geneticists at the Beef + Lamb Genetics conference in Napier in 2017, says Robert Peacock of test host, Orari Gorge Station.

Breeding sheep resistant to internal parasites has long been a passion of his: it was the subject of his thesis at university 25 years ago and he’s been putting theory into practice ever since with the family’s Romney stud and, in turn, commercial Romney ewe flock on the station. Adult ewes haven’t been drenched since the mid 1990s and ewe lambs get three or four drenches at most.

That’s despite the property, which stretches from the top of the Canterbury Plain behind Geraldine back into the Four Peaks range, facing a regular worm challenge thanks to its reliable summer rainfall and grass growth. That, and the station’s scale (see Farm Facts), made it an ideal place to run the LISPT.

“I was worried it might not go ahead if we didn’t host it,” he adds.

Nationally, with drench failures becoming widespread and labour to administer them increasingly scarce, not to mention global consumer demand for less chemical use in food production, he believes the project’s essential for the future of the NZ sheep industry.

“I know of stations that were three or four labour units down last season. They sold their lambs store at weaning simply because they didn’t have enough labour to put the systems in place to feed, weigh, drench and crutch lambs through to finishing.”

Besides support from Orari Gorge, other breeders and Beef + Lamb NZ Genetics, MPI’s Sustainable Farming Fund has contributed $600,000 towards the test’s first three years’ work.

A report on the first year’s results is at www.blnzgenetics.com/progeny-tests/sheep-progeny-tests – scroll down the page to find the link.

FARM FACTS:

- Land: 4300ha split 10% flats, 15% downs, 75% steep hill/ tussock rising to 1100m.

- Rain: 1200mm/year average at homestead.

- Stock: 23,000 stock units; 50% sheep, 25% cattle, 25% deer.

- Commercials: 7000 Romney ewes, 450 Hereford cows, 1550 English Red hinds, 200 stags.

- Studs: 1200 Romney, RomTex SufTex ewes; 250 Hereford cows.

- 7 full time staff.