Priceless value of good dirt

When a series of flash floods hit a Southland farm its owners took the event as a warning of things to come. Lynda Gray reports.

When a series of flash floods hit a Southland farm its owners took the event as a warning of things to come. Lynda Gray reports.

A CHANGE TO MINIMAL TILLAGE AND multi-grazed crops is the next chapter of development at the Frew family’s Southland sheep and beef farm.

Washout weather in October 2018 was the catalyst for change. Flash flooding and thunderstorms – three times over five days, each affecting different areas of the farm – annihilated 50 hectares of crops and young grass as well as farm tracks and infrastructure.

Some said it was unlucky and unusual to be struck down by the extreme weather, but Dan and Brett questioned if the ‘unusual’ would become ‘usual’ with climate change. They treated the weather bomb as a timely warning.

“Mother Nature made it obvious to us how exposed our crop and pasture renewal system was to extreme weather,” Dan says.

The soil was literally stripped off slopes and on the flatter areas washed overland into creeks. Although able to buy and resow seed, which more or less doubled farm expenses the following year, the soil was gone for good. It brought home the priceless value of good dirt.

What’s unfolded since is a minimal-cultivation policy, along with mixed and multi-grazing crops to maintain soil structure, health and porosity. The approach is aligned with regenerative principles but adapted to their large scale and reasonably intensive system.

“We’re trying to take the best parts of regenerative farming principles and incorporate them into our traditionally based system to find a happy middle ground.”

In doing so it’s created opportunities to reduce workload and costs and improve ecological health which goes hand-in-hand with better animal health and welfare.

Over the last two years single variety crops have been replaced with 50ha of multi-species winter crop which also get a light grazing in summer, and another 20ha of summer crops that get three to four grazings spread over summer, autumn, winter and spring.

“We see these crops as the new opportunity because we can graze them through summer, lock them up for regrowth during autumn which can provide about six tonnes of drymatter for winter feeding.”

Undersowing swedes

First year crops are swede-based with underplanting of Italian ryegrass, ryecorn, plantain, and Balansa clover. Over the next few years the mix will broaden to include up to 10 species. In November 2021, 33ha were sown. The seed mix (6kg ryegrass, 2kg ryecorn, 750g plantain and 500g clover) was broadcast with lime and 800g of swede direct drilled overtop.

In the sunnier facing paddocks where there was good early season growth a light grazing by lambs took the bigger leaves off the swedes, letting light in to kickstart growth of the underplanted varieties.

On the damper south-west paddocks that have traditionally produced average to poor single crops of swedes the companion plant species have grown faster to provide good bulk and soil cover. Where the swedes have grown but at a slower rate, the crop was block grazed by 1000 ewes from June 1 until August 20. They were generally shifted every second day, but daily if conditions were overly wet. The short term block grazing, with no second rotation, is crucial for soil recovery in an intensively winter grazed system, Dan says.

“You can see the benefit of worm activity in reconditioning the soil.”

After winter the crop was left to let the grass, ryecorn and plantain regrow acting as a catch crop and also providing grazing for single lambing or lambed ewes until the establishment of a second crop or perennial pasture mix.

Second year crops are kale or raphanobrassica-based with kale, leafy turnip, ryecorn, Balansa clover and Italian ryegrass.

Ultimately, all-grass wintering might be what they’re after, Dan says, but the question is how to get there, or how to get there by modifying the farm system.

“I think we’ll keep developing the multi-grazing option because we hate mud. There’s nothing to gain from having exposed mud so we are trying to minimise this through careful grazing and having a living plant in the soil at all times. We need to reprioritise taking into account both soil biology and soil chemistry.”

It’s early days to assess the economic costs and benefits of the minimal tillage and multi-species and grazing system, although Dan’s convinced that there’s been an improvement in crop and pasture consistency along with soil condition and porosity. Also, dropping out cultivation, apart from aerating and direct drilling, has meant a massive reduction in costs and inputs such as insecticides, weed sprays and glyphosate use.

“Once we get the system fine tuned we think we’ll be able to reduce synthetic inputs further without the wheels falling off.”

In the meantime the Frews are working with AgResearch scientist David Stevens to help quantify some of the gains, and factor in the dollar-equivalent benefits of a system that is more weather-resilient and produces lamb and beef that aligns with environmental goals and consumer expectations.

“We believe we are working towards a better system financially, environmentally and for the health and welfare of livestock.”

Participation in the Makarewa Headwaters Catchment Group has given the Frews some good environmental tips. The group, with funding from Thriving Southland which coordinates and supports 18 catchment groups in Southland, got behind a Land Utilisation Capability Indicator (LUCI-Ag) project to identify N, P and sediment loss hotspots and pathways in the catchment. Dan says its helped them identify the different land classes on the farm and the fragility level of each area.

“It gave us a better idea of where we could make the most cost effective gains with environmental mitigations such as riparian fencing and plantings. It’s also given us a better idea of how to match stock class and soil type for winter grazing.”

Next on the cards is a catchment-wide pest reduction programme to reduce the number of feral deer, pigs and goats to reduce the damage of soil and waterways.

Red light for red clover

In 2017 the Frews were undecided about whether to stick with red clover or replace it with raphanobrassica.

An 18ha area of red clover was established in 2013 for grazing by multiple lamb bearing ewes in the spring, and weaned lambs in summer destined for heavyweight contracts. The upside of red clover was that more could be fed on a relatively small area; the downside was the no go grazing from May until October.

The Frews felt that the area grown needed to increase to 10 to 15% of the total grazing area to provide greater scope for lamb finishing. Another two paddocks were established in 2018, but they were severely damaged by the storms.

“We didn’t replace it which in hindsight was a mistake, because it didn’t perform well,” Dan says.

They decided to call it quits with the clover.

“Although it’s the best for animal performance, it’s hard to manage unless you have a significant amount in your system.”

Raphanobrassica (Pallaton Raphno) was tried as an alternative summer finishing crop. It grew well but as a single species didn’t provide a complete diet for lambs and was reflected in disappointing lamb growth rates.

“It performs brilliantly but it needs to be grown as part of a multi-mix to maximise lamb performance.”

Looking back and forward

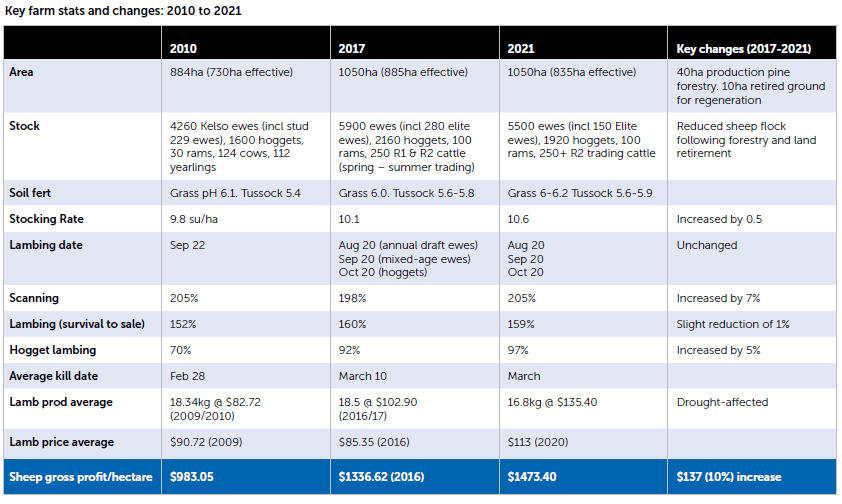

The Frew family and their sheep and beef developments were profiled in 2010 and 2017. In each story the family has pushed performance by questioning what they’re doing and following through with change where necessary.

In 2010 Mervyn and Marie (Dan and Brett’s parents) explained their move from lamb trading to lamb finishing in the early 2000s when very few others were brave enough to take the plunge. The next story in 2017 looked at how the family had increased lamb survivability by 15% over nine years through a mix of improved genetics, development of a triple shift lambing system, and strategic feeding of winter and summer crops. The had also recently bought an adjoining 165ha dairy run-off/cut and carry cropping block for conversion to sheep grazing.

Since then Mervyn and Marie have gradually eased out of the day-to-day involvement and last year sold the farm to the brothers. Most of the land is owned by Frew Farming Ltd comprising Dan and Brett’s families. The remaining land is retained by the family trust and leased to the brothers.

The washout weather of four years ago has been a life changing experience.

“It’s been financially, physically and mentally draining and we’ve been in recovery and consolidation mode ever since developing a new crop and pasture system,” Dan says.

But they’re looking forward to some bold moves over the next five years that will leave them with a more resilient system for the wetter and warmer weather that appears to be taking hold in Otapiri Gorge.

A priority is to remediate soil quality issues on the ex-dairy block bought in 2017 by introducing organic matter which could involve deferred grazing, bale grazing and perhaps composting.

“We think composting has great potential but it’s a matter of how to make this work at scale without having to cart and carry too much on to the farm.”

At a broad system level they want to reduce inputs, especially chemicals but are aware of the need to monitor carefully to maintain output.

At the same time they want a balanced and enjoyable lifestyle with their families.

“The thunderstorms and what it caused taught us how life can literally change in front of you, so you need to make the time to enjoy it.”

Jam for dirt bikes

‘Farm Jam’ an annual dirt bike event held on the farm since 2007 has been put on hold since Covid.

Dan, a former pro motocross freestyle competitor, and Brett, a pro BMX/MTB competitor, masterminded and grew the event which in 2018 attracted 80 competitors and 3000 spectators.

“We might revisit it, but not in the same form,” Dan says.

Meanwhile, the Frews host occasional film crews seeking locations for adrenaline and extreme-type pursuits.