BY: TOM WARD

Some 20% of the South Island is termed high country, about 2.4 million hectares.

Governance of pastoral leases (PL) by the Land Act 1948 is the result of a long history of changes.

Originally, in the 1850s, lessees were given access to the high country for minimal rental, just to encourage these lands to be occupied. Over time the leases were formalised, initially for five-year terms, then eventually out to 35-year terms in the mid-1920s. There was still no security of tenure, and rentals were set at expiry by public tender.

High country leases renewed in 1918 for example, a year of endless optimism, were very high, causing extreme distress during the depression years of the 192’s and 1930s. Some rents were suspended during those years and many farms became run down.

The 1948 Land Act set out to both (a) put an upper limit on the annual rent, and (b) give the runholder better tenure, which would encourage them to take a long-term view of their landholding.

The result was a 33-year lease, perpetually renewable, with rent reviews of 2.25% of the land exclusive of improvements (LEI) every 11 years. This lease is called a pastoral lease (PL). All improvements, including induced fertility, would be owned by the lessee, who nevertheless would be required to farm under strictly pastoral conditions.

Principal among these restrictions is a block on land development. Leaseholders had the right to quiet enjoyment and could stop the public accessing the property. As successive sales of leases showed, the runholder held a “virtual” freehold title, not through owning the soil, which he did not, but through holding a right in perpetuity to occupancy.

What is important to understand, and a point misunderstood by many New Zealanders, is that the Crown had reduced its property rights to very low levels. Under the legislation it could never hope to resume and farm the land, and its only source of income is rents which were deliberately set low. This fact had implications for setting rents and for tenure review (TR), which I will deal with in a later article.

On the whole, the 1948 Land Act achieved its aims of maintaining the soil quality and natural ecosystems in the fragile high country areas, while giving a much better tenure framework to the lessee.

By the 1990s there was runholder frustration with limits on development, and public frustrations with limits on access to the high country. Early in that decade, under the 1948 Land Act, some leases were subdivided by mutual agreement between Crown and lessee. Areas with conservation values, generally the higher altitude areas, were returned to the Crown (Department of Conservation-DOC) and destocked, and the lower, more productive areas, with little areas of conservation value, transferred to the former lessee as freehold.

The Crown Pastoral Lease Act of 1998 (CPLA) formalised this activity, which became known as TR, with the minister of the day stating that about one million hectares of conservation land would eventually be returned to public ownership.

There are 171 PLs covering 1.2 million hectares. About 313,000ha has been transferred to DOC since 1998, and 353,000ha has been transferred to former lessees as freehold.

Over time, TR has become contentious, with critics claiming the Crown has been disadvantaged through (a) loss of natural habitat on the privatised areas, and (b) excessive remuneration to the former lessees.

In 2007 the Labour government strived to bring down TR valuations by including amenity values in the rent calculations (which the government hoped would reduce the attractiveness of PLs) and by excluding lakeside property from TR.

In late 2007 the Land Valuation Tribunal ruled that rents could only be based on pastoral values and the new Government reversed the policy of excluding lakeside properties from TR. Simultaneously, PL rents calculations were moved to be based on a lease’s assessed productivity.

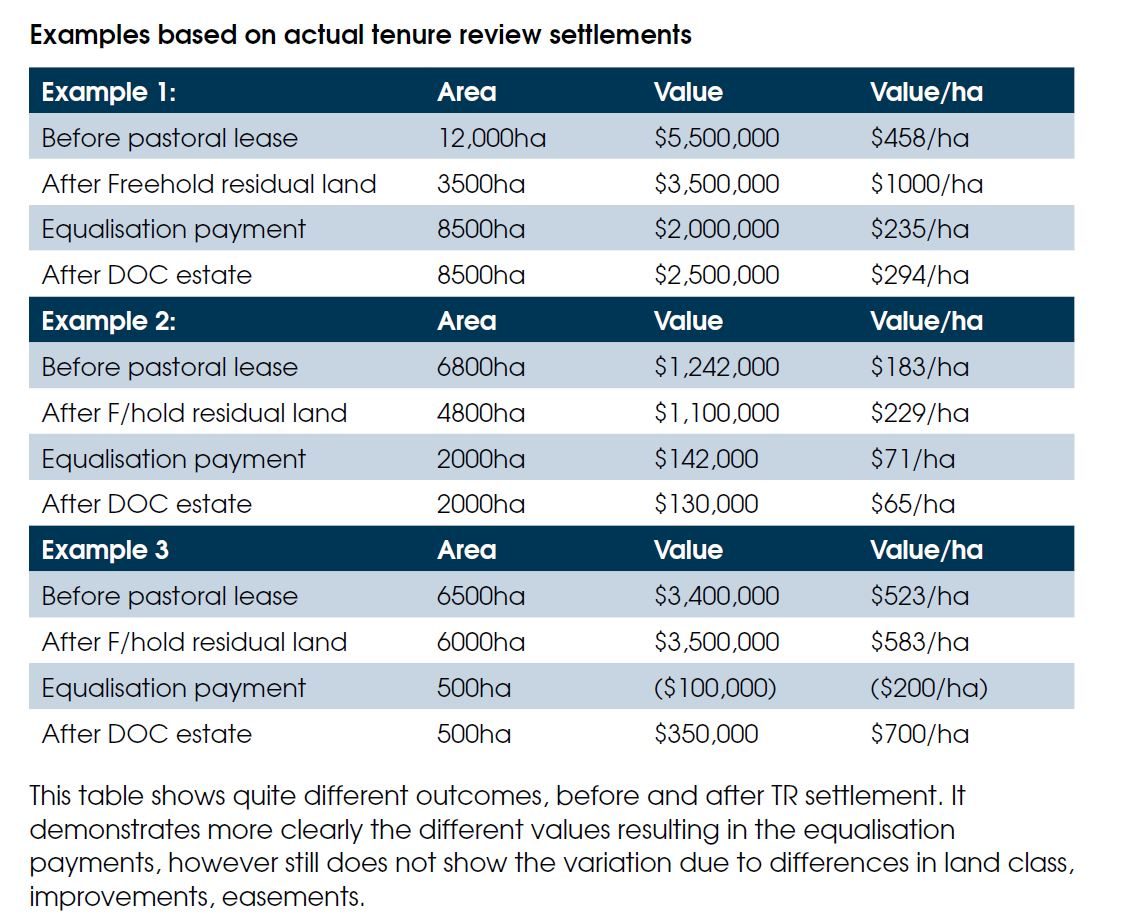

There is a general lack understanding of the valuation methodology and its effect on TR settlements, contributing to the public’s view that the Crown is being “ripped off”.

Furthermore, using high end sales of stations like St James Station, Birchwood, Mototapu/Mt Soho, Hunter and Ryton Stations, all Pastoral Leases, to explain the high values the Crown has paid for TR settlements, is only a part of the equation.

In February 2019 LINZ and DOC minister Eugenie Sage announced TR would end, and that she would bring to Parliament the Pastoral Land Reform Bill.

Notwithstanding this Government’s planned changes to the Land Act, the rules have already changed with farmers subjected to updated RMA rules, District plans (PC 13), and the 2017 Environment Court decision by Judge Jon Jackson (April 13, 2017).

Applying fertiliser is now a consented activity, however farmers are still required to control pests and weeds which are prolific.

- Tom Ward is a farm management consultant based in Ashburton.