Opportunity cost of ewe wastage

In any flock some ewe wastage is inevitable, however there are ways to reduce wastage and gain some of the potential financial rewards. Rachel Joblin reports.

In any flock some ewe wastage is inevitable, however there are ways to reduce wastage and gain some of the potential financial rewards. Rachel Joblin reports.

What’s an acceptable level of wastage in ewe flocks and how do some farm farmers have lower rates than others?

Deaths, missing and culling early for either not being in-lamb or failing to rear a lamb has an opportunity cost. The cost is borne in several ways with the requirement to have a higher number of replacement ewes entering the flock. A bigger replacement rate means fewer lambs available for sale. Ewes that are carried but do not rear lambs result in fewer lambs for sale and the lost opportunity to sell a ewe if she dies before sale.

Recent studies by the International Sheep Research Centre at Massey University followed 13,142 ewes from three farms for their lifetime. Of the ewe hoggets that started the study 50% were culled prematurely, 40% died onfarm and only 10% made it to six years old.

The annual rate of onfarm deaths ranged from 3.5-40.2% (the last was an outlier in a small group of older ewes). The average annual death rate was about 8%.

Pre-mating body condition score was important – ewes in better BCS were less likely to be culled prematurely or to die onfarm. It is highly recommended to BCS all ewes at least twice a year (post-weaning/pre-mating, and at pregnancy scanning) and have a management plan for poor BCS ewes.

Half the ewes in the study were culled prematurely for various reasons – ewe culling decisions, particularly for younger ewes, have the potential to have a large impact on wastage.

Findings from this study showed hogget mortality ranged between 4% and 10% and for every 1kg gained between scanning and set-stocking there was a 10% reduction in the likelihood of the hogget being a wet dry.

Hogget culling decisions on reproductive performance such as removing scanned dry or wet dry hoggets from the flock can have a big impact on wastage. Some farms intentionally retain more hoggets than required as replacements to allow for this culling pressure.

Four out of 10 ewes in the study died onfarm and the majority of deaths occurred between set-stocking and weaning (over the lambing period). While causes and timing of death were not determined, some form of monitoring during this period (such as a pre-lamb cast beat) may reduce death rates.

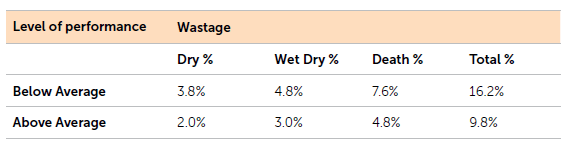

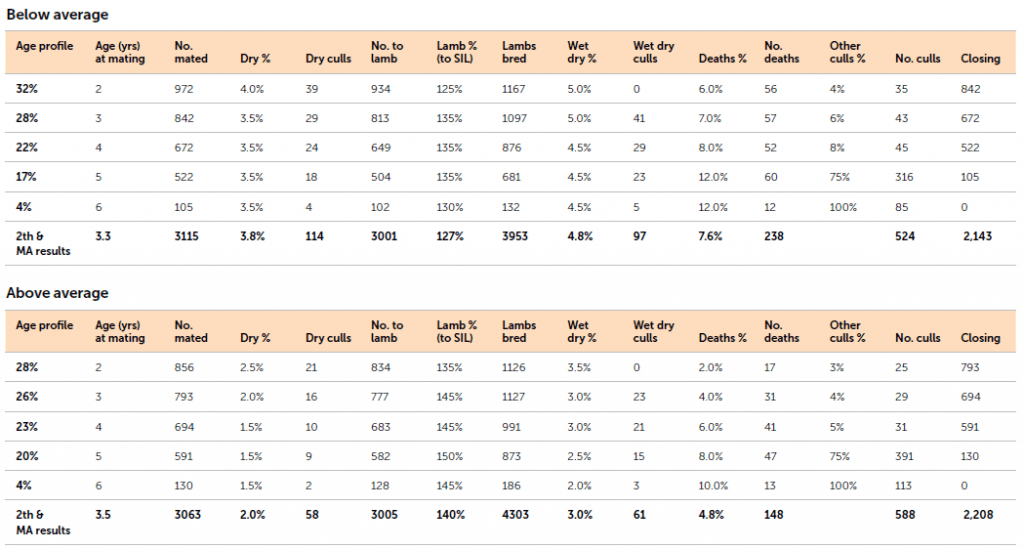

By looking at two 3000-ewe flock profiles that compare below average and above average wastage we can begin to see the cost to a business.

For the below-average flock to be self-replacing it requires 972 (32%) two-tooths on hand at mating. This compares to the above average flock that only requires 856 (28%). Taking the difference of the 116 two-tooths and a rearing cost of $98/head, it equates to $11,368.

Lowering the death rate from 7.6% down to 4.8%, sees 90 fewer MA ewe deaths. At a cull ewe value of $140/hd that equates to $12,600.

When analysing flocks, we see that when wastage (dry dries, wet dries, and deaths) is consistently below 10%, the likelihood that flock lambing more than 140% is significantly higher and physical and financial performance is stronger. In this scenario when wastage is low it equates to 350 additional lambs born. Valuing store lambs at $110/hd, this comes to $38,500.

Combining the above, we get a variance in net returns of $62,468.

The opportunity for greater use of terminal sires exists when wastage is low and lambing rates are lifting as a lower percentage of maternal ewe lambs from the total number of lambs born are required as replacements. The benefit of this is greater use of hybrid vigour from terminal sires resulting in heavier lambs at weaning.

Two of the key policies we see having a significant impact on ewe wastage are the age structure of the flock and feeding of the ewes at key times.

Body condition scoring a minimum of twice per year and developing an effective management plan for light ewes, alongside a plan to feed them to meet their nutritional requirements throughout the year, is one of the easiest ways to improve performance and reduce wastage.

The older the ewe, the more likely she is to die – worn teeth can limit feed intakes especially grazing low covers, and metabolically she becomes more fragile.

The counter argument is that if a ewe has successfully reared a lamb each year, has not been culled due to poor teeth, feet or udder and has not died then she has earned her place in the flock for another year.

We do know through information we collect that the mortality rate of older ewes is between 9% and 12% typically versus an average across mixed age ewes on those farms of 6%.

Collecting information on your own ewe flock such as total wastage (scanned dries, wet dries and deaths), timing of these deaths and likely reasons is the first step to understanding ways of reducing wastage and gaining some of the potential financial rewards. Some ewe wastage is inevitable but there are ways to influence it in your favour.

- Acknowledgement to the Ewe Longevity Trial funded by Beef + Lamb New Zealand, Massey University and The C. Alma Baker Trust.

- Rachel Joblin is a farm consultant with BakerAg.