Nursery for the future

Native trees and shrubs grown in the farm nursery provide a fresh focus for a Waikato farming couple. By Glenys Christian. Photos by Emma McCarthy.

Adam Thompson leads by example when it comes to persuading farmers of the benefits of planting the least productive areas of their land in natives.

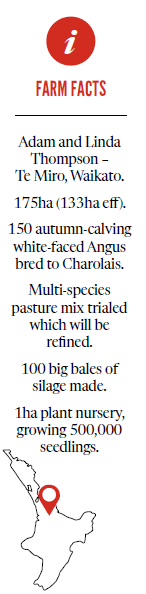

On his Te Miro beef farm just out of Cambridge in the Waikato he’s retired 14 hectares since the property was bought with wife, Linda, and there are plans for many more, as well as continuing riparian planting.

On his Te Miro beef farm just out of Cambridge in the Waikato he’s retired 14 hectares since the property was bought with wife, Linda, and there are plans for many more, as well as continuing riparian planting.

His onfarm Restore Native Plant Nursery is supplying plants to up to 150 sheep, beef and dairy farmers who’ve embarked on their own planting plans with natives they can buy at an affordable price.

“There’s a lot of misinformation about the cost of establishing natives,” Adam says.

Some estimates range from $40,000-$50,000 a hectare.

“But most come in at from $20,000-$25,000 and they can be as low as $10,000.”

A lot of that depends on the distance between plants. While 1.5 metres is “the gold standard” gaps of 2m are fine and up to 2.5m in some cases.

“Once you’ve got the ground cover you can bring in whatever species you like.

“If you don’t love it, you won’t look after it, so why have a scrappy hillside you don’t love?”

About 500,000 plants a year are grown in the 1ha nursery and he’s invested in automation and upgraded infrastructure to double that production this year, with expansion planned.

“I’m the sort of person who does everything a million miles an hour,” says the 35-year-old.

“I like to see what works and what doesn’t quite quickly so we can evolve and do more.”

He was born in Kaitaia but his parents moved into dairying and market gardening in the Waikato. Venturing south after he left school he worked fencing on a Landcorp farm at Mossburn, then returning to the Waikato he set up a mortgage broking business in Cambridge 15 years ago, of which he still owns one third.

He and Linda, who is the head of energy and climate for Fonterra, lived on a 12ha farm down the road where they had built their dream home and planted many trees, prompting admiring friends to ask if they could buy seedlings from them.

“We had lots of ideas on the environment and we needed to fund a way to make more money to build something we were really proud of,” he says.

When two adjacent farms, totaling 175ha, came up for sale within a year of each other the prospect was too good to resist. They’d been run by two brothers, the oldest of whom was in his early 80s, but were sorely in need of new investment.

“They were primarily rearing and selling beef calves but there were a dozen sheep we couldn’t muster in the gorse.”

He has recently built a new house nestled into a 14ha covenanted bush block which provides a great playground and connection with the farm and nature for their children Clara, 5, and Maverick, 3.

They then looked at what land should be retired with a 2ha block of pines being taken out for milling progressively and replanted in natives. Next up, about 20,000 plants, mainly manuka and kanuka, will go in on a steep face as erosion control.

They run 150 autumn-calving cows, making the switch from spring last year.

“We grow more feed in July than in February,” he says.

“So we wean and sell in November. It’s a better market, and we’re not offloading stock into a declining market like we had been in the past.”

Good for morale

The change has also brought about “a massive shift” in animal health. There are very few metabolic issues during calving, compared with spring. Adam says it makes a big difference to morale for farm manager James Kilgour to be able to check calving cows with some light and without the mud associated with spring calving. He’s in charge of the day-to-day operations of the farm but splits his time with the nursery as well.

Only the young stock receive a zinc bolus, with the cows getting a selenium and B12 injection three times a year.

Specklepark and more recently Charolais bulls are run with their white-faced Angus cows for six weeks. They come from Kia Toa Stud, Te Kuiti and also Silverstream Charolais out of Akaroa in Canterbury.

He says the calves grown are like a Ferrari.

“If you feed them they’re great but they don’t perform as well as traditional breeds if the feed is not kept up to them.”

Stock are weighed every six weeks with the top line of weaners put on to summer crop and finished as 15-month-olds before their second winter, killing out at between 250-300kg.

Kale was previously grown as a winter crop but now that they are finishing their weaners before the second winter this has reduced the labour and environmental impact, allowing a focus on the nursery during the busy winter season.

Initially Adam thought he would trade cattle but soon realised a lot of their country isn’t good enough for finishing.

“The breeding cows are a good fit for this country and we finish what we can and try to do that well rather than carrying too much stock.”

About 100 big bales of silage they make around Christmas are fed out to deal with the high feed demand in autumn. As part of a regrassing programme last year a 16-species regenerative agriculture mix was trialed containing chicory, plantain, and two clovers, giving a good balance of bulk and high protein feeds.

“The sunflowers looked cool but we didn’t find the crop had the high protein feed we required in summer to continue putting weight on our weaners.”

He plans to try a mix of just six species on a couple of hectares this year.

Fodder beet is used as autumn feed – “but I wouldn’t feed it in winter because of the soil damage”.

Their farming dovetails well with running the nursery.

In winter they can spread the cattle out more and if it’s quiet at the nursery they do more on the farm.

“You can’t farm by a diary or run a nursery on one. You have to roll with it.”

Olsen P levels on the farm were between 5 and 6 when they took over the property with little inputs having gone on for the last 40 or so years. As well as a lot of lime there have been consistent applications of traditional fertiliser over the past four years along with the regrassing programme to get nutrients to start to come into balance.

About 30-40ha has some gorse on it which was sprayed by helicopter and along with blackberry, is being followed up on foot.

Adam is near where he wants to be with improving fencing on the better country to allow better and easier stock management.

“We’re very much focused on developing our good cattle country, not our hills,” he says.

“It’s no use saying to farmers they should start planting natives on the most productive part of their farm.”

So he’s able to help them out on starting a planting programme, giving site location and fencing advice.

Keeping cost down

To keep costs down local seed is collected, a point of difference from other large nurseries based outside the Waikato.

“I’m that crazy guy who drives around with a pole pruner and secateurs,” he says.

About half the seed comes from bush remnants on the farm.

“Anyone can grow a plant but it’s not so simple to get the quality of plant at the size it needs to be to plant at the right time of year.”

Some plants will need to be sown months apart to achieve this as they’re all grown outside.

“We give them a hard time in the nursery because they need to thrive when they’re planted out on farms.”

In order to get the root-to-plant ratio right they’ll be trimmed off at 500-600 millimetres tall – “There’s no point getting them to a metre and then they just fall over.”

Restore Native specialises in a pioneering plant mix containing a dozen species, including manuka, kanuka and cabbage trees which will thrive in difficult conditions. Tree lucerne and banksia are also included to provide bee and bird fodder as they flower when few other plants do.

“That gets an incredible symbiosis going on.”

Planting in the nursery will usually begin on Anzac Day but was delayed this year because of the dry weather, which has added some extra pressure as a planting service is also offered. About half of their plants go on to farms across the Waikato so there’s only a relatively short window of a few months to do the planting.

There are six permanent workers employed as well as the same number of casuals, with Adam hoping to also make them full-time. Recently people have been drawn to the work from a variety of different backgrounds, with an airline pilot and an occupational therapist amongst them.

“They’re wanting a change of scenery and to have a bit of fun.”

That’s provided by barbecue lunches on the back of the ute when they’re planting out. And Adam works on the idea that there’s a better planting success rate with workers specialising in just one of the tasks involved such as digging holes or planting seedlings with more care.

With most of their clients being farmers he aims to make their planting projects as cost effective as possible.

He says they are selling plants at $2.25 to $2.50 when the market is $3-$4.

“We’re blessed that we’re dealing with progressive farmers who want to get more out of their land”.

He finds it rewarding to see what they’re planted. “We all want to win together.”

He’s also continually looking at expanding the range of natives which might be able to grow in the Waikato, such as pohutukawa and kaka beak, by trialling them in the nursery.

Last year he applied for the third time, was accepted and became one of four New Zealand finalists in the Zanda McDonald Awards, which links future agriculture leaders. He says it was a fantastic experience and still keeps in touch with the other farmers he met.

“It’s hard when you’re doing new things and pushing the boundaries, but linking up with other like-minded people in agriculture has really helped me to progress in my own business and help others.

Adam wants to grow trees for the rest of his life and leave a legacy on their farm and with others, that his children can be proud of.

“I’m keen to make sure of that.”