Money better in the bank

Critics say the government would be better off selling its farming operation, Landcorp. By Terry Brosnahan and Glenys Christian.

Landcorp’s head disputes its poor-performing label and argues it is on the road to salvation.

The State-Owned Enterprise’s chairman Warren Parker said Landcorp has improved since a Treasury-commissioned 2020 report.

He argues its farms should be benchmarked to similar farms.

“It needs to be on a like-for-like basis.”

Parker said the report compared its tougher farms with private, better farms.

Under the land classification system, he said, 53% of their farms are class 6 and 7 (poorer soils and steep).

“On our irrigated farms in Canterbury we are comparable.”

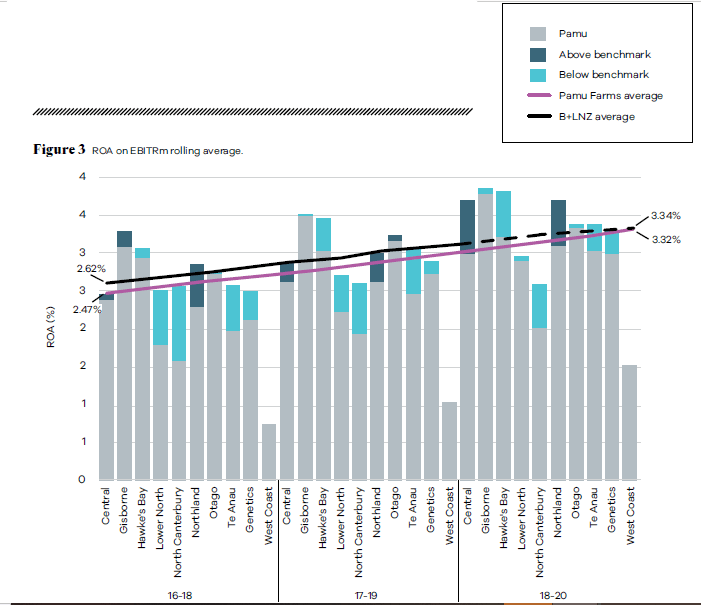

Critics say Landcorp exists to put money into the Government’s coffers, the consolidated fund. Landcorp’s return on assets in the past five years is 3.3%. It is not as bad as Kiwi Rail and NZ Post but they are providing essential services. Other SOEs have recorded 24-27%.

Critics say it would be better to sell off Landcorp farms and put the money in the bank. Landcorp farming’s brand name is Pamu.

Since the report, Parker said Landcorp had acted on some of the report’s criticisms, particularly on improving its transparency.

“We’ve provided better linkages between former forecasts and updated forecasts.”

He says that when Landcorp submits a new business plan to Treasury it outlines why there are variances between the original and current forecasts.

Parker was asked by Country-Wide for a copy of its official business plans which the SOE provided to the Treasury for the past three years to see if the goalposts have changed and if executives are delivering on promises made in 2020. He refused, citing commercial confidentiality.

Parker did send some dairy benchmarking figures for 2021, not 2022. Pamu’s earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) is $2477 to $3216/ha. It said the industry average is $2867/ha.

Ag economist Ray Macleod said EBITDA/ha is a poor measure.

“What percentage of the feed budget is grown and how much is external grazing or imported feed?”

Macleod agrees with the report which says it is difficult to assess Landcorp because of lack of information, transparency and “moving targets”.

“Having been a long-term reader of Landcorp’s annual reports, they are best described as murky.”

The benchmarking put ewe stock and death rate at 8.7% (2021-2022 year was 13.1%) compared with the industry’s 5%.

Parker said the higher ewe loss was an area of focus with poaching on one farm.

Macleod said one farm did not impact a sheep flock as big as Landcorp’s which is 435,000-440,000.

Landcorp’s farm performance does not include its corporate overheads.

Parker said a management fee and cost structure are included, but not the overhead costs.

Critics suggest the overheads are about $25-30 million and likely to include their off-farm ventures. Parker said the corporate overheads were $19-21m.

Macleod argues if an overhead is not allocated a return on assets on the books it will look favourable.

The overall result doesn’t support a good return on assets, he said.

“For example, in addition to overheads, where were the dairy replacement costs being allocated?”

This was not shown in the accounts. How was the sale of dairy culls being allocated because in the annual report it is in cattle trading?

“So what is the basis for the benchmarking?”

Parker said the low cash rate of return on assets (3%) is similar to private farms and there had been a significant increase in equity with the revaluation of sheep and beef assets. Critics say revaluation is smoke and mirrors. What is the operation’s return before revaluation?

Parker rejected criticism of Landcorp’s off-farm investments being below projections, saying they were operating at break-even or profitable. He said it was the correct move to lift market returns and land use enterprises. Sheep milking would have a lighter impact on freshwater.

Melody Drier and Spring Sheep Dairy (SSD) were linked to the supply chain and Landcorp was respectively 35 and 50% shareholders. Covid and China market changes for infant formula registration have ‘slowed progress’.

“…but we are seeing markets opening and opportunities for market diversification emerging now.”

Asked for a return on assets for the sheep milk, he replied they were still growing supply. Parker is comfortable with present plans and value accretion, saying SSD isn’t yet equity accounted.

Critics say there needs to be a full investigation to see what has gone on with the management of Landcorp’s off-farm investments.

State-owned footballs

It’s been 36 years since Landcorp was formed, a state-owned enterprise tasked with farming state-owned land to “grow New Zealand’s finest natural products”. Dr Nicola Dennis takes a close look at Landcorp’s results and questions its value to the NZ economy.

It’s election year which means it is time to start booting the political footballs around the beehive lawn. Farmers, teachers, police, gangs, beneficiaries and immigrants can all look forward to having their futures planned out by lonely retirees on talk-back radio. One political party will argue that New Zealand is a country approaching destitution, filled with hungry and illiterate children anxiously waiting on housing and healthcare. The other will argue that, no, everything is either fine or on its way to being fine. One of them will win and fiddle around the edges pecking holes in their favourite victims for the next three years. If red wins, there will be more regulatory jabs at farmers, landlords and other private enterprises. If blue wins, the public sector will be trimmed, purged and audited into submission.

In amongst it sits NZ’s largest farmer and permanently underperforming state-owned enterprise, Landcorp, which can’t expect much love from either direction. National and ACT want to kill it via farm sales or private leases. Labour and the Greens want to torture it into an example of idealistic farming standards. Te Pati Maori would point to the Treaty of Waitangi. This would have to be a major reason why Landcorp continues to persist despite nobody being too fond of it – it is one of the state’s hidey-holes for illegally confiscated Maori land.

What is an SOE?

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) came into being on April fools day 1987. It was part of the radical governmental reforms of the 1980s that some people called Rogernomics and others called neo-liberalisation. I call it a massive swing from “government knows best” to “the free market will have to save the country”.

Government departments and assets were repackaged into government-owned companies. The idea being that they would be more efficient if run as separate legal entities. It also wrapped them up in a neat little bow for sale during a time when the state was looking to trim some fat.

This meant the Department of Lands and Survey, which was managing Crown land, got divided up into the Department of Conservation, the Department of Survey and Land Information and Landcorp. Landcorp was probably allocated land the Crown intended to sell off to private buyers, except the 1980s weren’t great years to try offloading farmland.

Under the State-Owned Enterprise Act of 1986, the principal objectives of an SOE are to be (1) as profitable and efficient as comparable private businesses, (2) a good, equal-opportunity employer and (3) an organisation that is socially responsible towards the community it operates in.

How does Landcorp stack up as an SOE?

Landcorp, trading as Pamu, sits on close to $2 billion in assets and returns a measly $5m dividend to the NZ taxpayer each year. Their lambing percentage is average at best (130–135% including hoggets). The Landcorp dairy cows flail significantly below the national average with 350–375kg MS a cow over the past three years.

Over the past five financial years, Landcorp’s staff turnover has been 25% for its 600+ workforce. Return on capital invested over the same period has been 3.3%. We can compare this to the return on capital investment for other “agricultural-ish” SOEs, such as AsureQuality (27%) and Animal Control Products LTD (makers of ‘Pestoff’ products) 24%. These particular SOEs will have benefited from Government spending on Mycoplasma bovis and the ‘Predator Free 2050’ programme. But even so, it is clear that Landcorp isn’t doing any better than leaving the money in the bank and, like so many of us, is simply farming for the fresh air and capital gains.

What is the purposeof Landcorp?

Landcorp clearly isn’t blowing the Treasury away with its financial performance. Although it wouldn’t be the only SOE in that category. KiwiRail Holdings Limited had $13.9 billion in total assets in 2022 and will probably never pay a dividend. Its operating balance is frequently in the red by hundreds of millions of dollars. But NZ is a better place with railways and inter-island ferries.

Likewise for a postal service. This is basically the Government providing essential services where private enterprise would struggle to survive. After all, Toll holdings was happy to sell the railway network back to the state for $1 in 2004.

But what hole is Landcorp filling? According to the Government, the purpose of Landcorp is to:

- develop the best systems for dairy, sheep, beef and deer farming

- genetically improve livestock

- offer a farm management service.

All three of these purposes are goals shared by existing private enterprises, as well as the Crown research institutes and universities. The country would not grind to a halt if the state stopped farming 6% of the national farmland.

Landcorp subsidiaries Focus Genetics and its joint ventures such as FarmIQ, Spring Sheep Dairies and Melody Dairies should be able to survive as private or state-owned enterprises without the support of some 24,000 hectares of land. It is worth mentioning that Treasury’s report was quite favourable of Focus Genetics but found Pamu foods, Spring Sheep and FarmIQ were underperforming. They also threw some shade on Melody Dairies where investments were made against Treasury advice.

There may be other reasons why it might make sense for the state to hold onto farmland. They just don’t seem like any of the reasons given.

Is it normal for governments to farm?

The word “farmer” comes from Old French “fermier” which means “lease holder”. This suggests that, historically, the person farming the land probably didn’t own it. Throughout the world today, government-owned farmland is fairly common. But it is usually maintained for reasons other than farming, such as defence training grounds or national parks. And then grazing permits are issued to private farmers. Or it’s in the form of research and training farms, such as what we see at AgResearch, Lincoln University, Telford, or prison farms.

When I try to find examples of other large-scale state-operated farms, I must trawl through screeds of harrowing literature on Soviet-era collectivism and Mao’s Great Leap Forward. These included confiscating private land in the name of idealism. That is not exactly the vibe that Landcorp is aiming for, but then again refer to the start of this article.

So which countries are still in the farming game? Definitive answers were hard to find. China is a good place to look. The golden child of communism has more than 51000 SOEs. For comparison, NZ has 37 and most countries sit in the 10–50 range. The World Bank estimates that Chinese state-operated farms make up 3.5% of China’s total farming by gross value of outputs. It is worth pointing out again that Landcorp holds on 6% of NZ farmland. While these numbers are not directly comparable, NZ could well have a higher proportion of state-operated farming than the world’s largest communist country.

The International Monetary Fund states that farming SOEs are relatively rare and that Lithuania is an obvious stand out for state-owned agriculture. I would like to know more, but it’s all in Lithuanian.

Let’s take a different approach and rule out our main export competitors. Australia doesn’t directly operate any state farming. Neither does America, land of the free enterprise, although the Bureau for Land Development leases vast amounts of land to ranchers. I have found nothing of note for South America or the EU.

When it comes to states that do farm, it might be a very small party. Possibly just NZ, China, Lithuania and a few buddies.

So now what?

This would be the bit where I get to punch in with my opinion. Only I don’t have one. Some say that Landcorp should focus on its core business and work hard to be a better farmer – pick itself up by its bootstraps and be the best, most sustainable farmer that NZ has ever seen. Although looking at the international figures, it seems that SEOs lag behind private businesses the world over. Why would Landcorp be the outlier?

Others say that Landcorp should focus more on innovation. Landcorp hasn’t done amazing so far, but that is what innovation is like – 99 ideas fail so that one can come along and blow the world away. However, I can’t ignore some of the uneasiness about some of Landcorp’s innovations so far. Setting up a milk drier against Treasury advice isn’t revolutionary. Neither is hopping on the coat tails of NZ sheep milkers. Sure Landcorp might be the first to milk deer, but why? The welfare concerns with milking an undomesticated animal must be extreme.

What else is there? Speed up the Treaty of Waitangi settlements? Switch to an American model and lease the land out? Plant it all in trees to give them a taste of their own medicine? It’s a hard shrug from me.