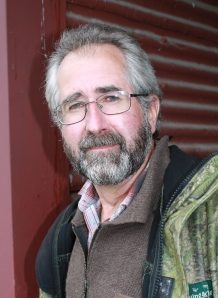

Researching issues for the deer farming industry has taken Geoff Asher to many places. Lynda Gray reports.

There have been a few times when AgResearch scientist Geoff Asher has questioned the wisdom of his career choice.

One was eight years ago during the rectal ultrasound scanning of young hinds at Mararoa Station in the Te Anau basin. It was early morning on a frigid June day so cold that even the winter feeding routine of stock was stalled due to the frozen diesel in the tractors. Meanwhile, inside Mararoa’s deer shed, Asher pulled on his rubber gloves for the highly invasive back-end procedure of red hinds.

“It was minus 14 outside and it was probably colder inside, and the only warm place was a deer’s rectum,” Asher recalls in typically dry and self-deprecating humour.

It was one day of a five-year project during which a total of 23,000 R2 hinds throughout the country and another 1000 mixed age hinds were poked, prodded and measured to find out the reasons for the poor reproductive performance in young hinds.

The upshot was a number of findings, one of the most significant being the importance of feeding to reach target liveweights before mating. Although the memory of that day lingers Asher says the misery was well and truly cancelled out at an advance party he attended several years later where deer farmers talked about what they did to get their young hinds to mating liveweight.

“It made me realise that all the reproductive research and data I’d helped accumulate over the years was starting to have an effect and make a difference.”

Asher, this year’s recipient of the prestigious deer industry award, is respected for his long-haul dedication to scientific research, particularly in the areas of genetics and reproduction.

‘It was minus 14 outside and it was probably colder inside, and the only warm place was a deer’s rectum.’

Scientific research is a risky business, he says, based on proving or disproving hypotheses, and the likelihood of success is a bit like kicking a ball over the posts in a rugby game. Some research is well-placed for success, a bit like a penalty kick or conversion in front of the goal posts.

“That’s the applied research that answers a particular problem. It gets a result and farmers like that and can understand it.”

But then there’s the long-term blue sky research that can span a decade or longer. It starts off in a particular direction but deviates as more knowledge and data comes to hand.

“You know you won’t get it over the goal post on the first or second attempt but over time you edge closer and closer.”

It’s what Asher refers to as transformational science because as the outcomes are assimilated and applied they lead to quantum leaps in advancement. In the deer industry a good example is the artificial breeding of deer that has evolved since the mid-1980s. Asher had played an important role in this while working at Ruakura Research Centre conducting research on the timing of hind ovulation and stag semen collection. At the same time vets had pioneered the actual artificial breeding techniques.

“The deer industry has been good at adopting that genetic technology and it’s helped dramatically improve the industry.”

For several years Asher has been chief adviser to DEEResearch, a joint-industry funded body that prioritised and allocated funding of about $1.8million annually to production-related research. The latest projects were focused on genetics, the environment and the physiology behind the feeding of deer.

The latest genetic developments were heading towards genomic breed value which in simple terms would short circuit by two to three years genetic advancements. The nutrition projects were looking at exactly how deer use the feed they eat which would lead to ways of selecting for deer that are more efficient feeders. The environmental research is an area Asher had championed a decade ago but was slammed by some for drawing unwanted attention. He’s pleased that it’s now a focus area and is somewhat philosophical about the time it’s taken.

“Topics and issues have their time and place but it’s a scientist’s job to be brave, step up and speak out even when the truth isn’t particularly palatable.”

He’s no regrets about a 40-year career of deer-centric research – pregnancy scanning in sub-zero temperatures excluded. The wide-ranging roles and projects have led to longstanding relationships across the industry, but it’s the one-to-one talks and small group discussions with farmers about the practical ways of using the research that he’s enjoyed most.