Leasing has helped Canterbury lease-holder Tom Magill into a first farm and he’s hungry for more in a red-hot property market.

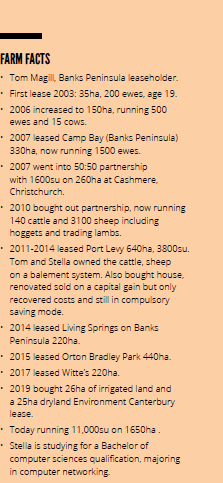

Leasing has helped Canterbury lease-holder Tom Magill into a first farm and he’s hungry for more in a red-hot property market.

Tom had a start in life at port-side Lyttelton, where he’d head across the harbour on weekend trips with his father to help friends with tailing, odd jobs and a spot of shooting.

He soon picked up the farming bug, spurred on by family moving on to a lifestyle block near Lincoln. Barely a teen, Tom started buying and fattening 30 to 40 sheep at a time on nearby sections.

At 17 he left school and went building then tried milking cows, but neither pushed his buttons. His spark came from his first hill country job at Purau, back on Banks Peninsula. As a casual musterer Tom met a couple of ex-shearing and fencing contractors who taught him their priceless skills: whenever there was no mustering work around he took to the shears. Helped by his partner on the boards, ex-pat German national Stella Bauer, his best shearing year while farming was about 6000 head.

By the time he was 19, Tom had his first farm lease – one of many that have helped him to now run 11,000 stock units on 1650ha with the help of two staff. The market for lease properties is much more competitive than when he started 18 years ago, he says.

“Every man and his dog wants to have a crack now. Especially on the Peninsula there’s a lot of people trying to add scale to their businesses to make them more viable. People who’ve been farming for quite a long time feel like they want to keep going so there’s quite a big demand for leasing properties – and they’re willing to pay the money for it.”

It’s a concern for Tom, who has always been careful with his capital and says the key to leasing is cost-control.

“You have to do as much as you physically can yourself until you get to a scale where you can start employing contractors. So, in the early days we were just flat knacker, doing everything to keep costs down.”

And over time he has become more discerning about the property he takes on. “I think you’ve got to watch that. You’re not going to do it just for the sake of doing it. As we got scale I wanted to make sure that what we were doing, we were doing properly.”

Whatever the property and no matter the return, Tom never loses sight of his ultimate goal: farm ownership.

He sweats over real estate listings and keeps his ear out for all sorts of propositions, but there’s a real lack of suitable properties for first-time buyers, he says. “They’re either too big or they’re chased by some other farming sector with money – like pine trees. Dare I say, it probably is getting a bit harder but you just don’t want to give up. There are always opportunities – and we will get there. And we’re building ourselves into a position now where it’s getting closer.”

He secured his most recent leases by public tender, benefiting from a reputation as a careful, diligent type. “I was fortunate to have opportunities come my way but I do believe that if you’re hard working and you’ve got the ability then people back you a bit more. The real key for me is to treat places like you own them. The people that you lease from appreciate that; they can see it – the weeds, the fences, everything. And it makes life a lot easier when you’re running farms anyway.”

Tom always looks for long-term leases so he can stamp his own mark, from fencing to fertiliser and pasture. His longest lease so far is five-plus-five-plus-five; a lease on Orton Bradley public recreation reserve, on the eastern side of Lyttelton harbour.

Before Tom and Stella took on Orton Bradley they had a three-year lease on a privately-owned 640ha property at Port Levy, a fill-in while the owner’s son was away getting more experience. It turned out to be a mid-career breakthrough, with Tom agreeing to a balement, whereby he took charge of the owner’s sheep on condition he returned them in the same state three years later. “We knew there was no point buying all his stock, because his son was coming home and he’d built up that genetic pool in the stock over the years. So, we just valued and counted the stock on the day, then at the end of the lease I had to present those age groups and numbers of stock back to him. And I paid bank interest on the value.”

Meanwhile Tom bought the cows and trading stock on the property because the owner wanted to introduce fresh genetics once the lease ended. In some ways, the balement agreement was a one-off arrangement. Tom owns the stock on all his other lease blocks “and it’s been good, because that’s where I made my capital gains.” Less tangibly, but just as importantly, the lease also helped Tom to get experience running stock on a bigger property.

For the past five years, Tom and Stella have called Orton Bradley Park home – a steady base as they build equity for a breakthough property purchase.

Tom says scale is vital to a farm leaseholder because it usually indicates equity, which in turn can open doors for bank finance. He and Stella now have a small property of their own at Greenpark, near Lincoln, courtesy of the equity they built in their 11,000 stock units across various properties. “That’s the biggest issue we’ve had. If you want to borrow money from the bank, livestock’s not actually a very good proposition for them to lend on. But over time as we’ve built scale, we’ve managed to build equity within our stock. The key for me is that because we’re largely a breeding unit, we have to buy the best genetics we can, so that we’re building a line of breeding stock that’s really saleable if one of the leases expires.”

The Greenpark block has helped his farming system too, balancing drought risk on his Banks Peninsula leases. “I was getting sick of having to bale out of my store lambs off our dry hill country. We’d lose sight of them and never really get any feedback as to how well our genetics were actually performing, so we wanted to go through the whole supply chain, from store to finished product. We’ve just been through a hell of a dry on the peninsula and this place [at Greenpark] really proved its worth. It might only be 26ha irrigated but it’s just been amazingly productive.”

Thanks to Greenpark he still managed to finish 5000 lambs this year.

Tom would love to have his own place on the Peninsula, which has traditionally lent itself to low-stocking, low-cost farming. Trouble is, the ocean-side hills with a smattering of bush are ripe for high-value subdivision so property prices are rich for a would-be first farm owner.

“I think we’d probably settle for two or three thousand stock units with leases to support it. Unless we can get some sort of equity partnership going – just being realistic with ourselves – I don’t think we’ll be able to go out and buy a 10,000-stock unit farm. There’s a lot of people trying to buy properties now other than just your Joe Bloggs farmer. I’d love to say it is going to be the Peninsula but who knows? Like I said, opportunity comes up.”