It’s not just the sale price

Kerry Dwyer reviews cattle trading margins year upon year, and says profitable beef production is based on getting the optimum growth rate relative to your cost structure.

A year ago I wrote an article on cattle trading margins, when beef prices were sitting at an all-time high in New Zealand. I didn’t make any predictions for the year ahead, rather, I looked at some of the gross profits made in the previous year. And now, as a comparison, it is worthwhile looking at what might have been achieved in the past 12 months when beef prices have eased somewhat.

The trading systems I used were fairly simple, based on several different buying options available at the Temuka auction in April and selling within 12 months. The Temuka sale is indicative of the South Island market and may be different from some North Island options.

Beef weaner steers

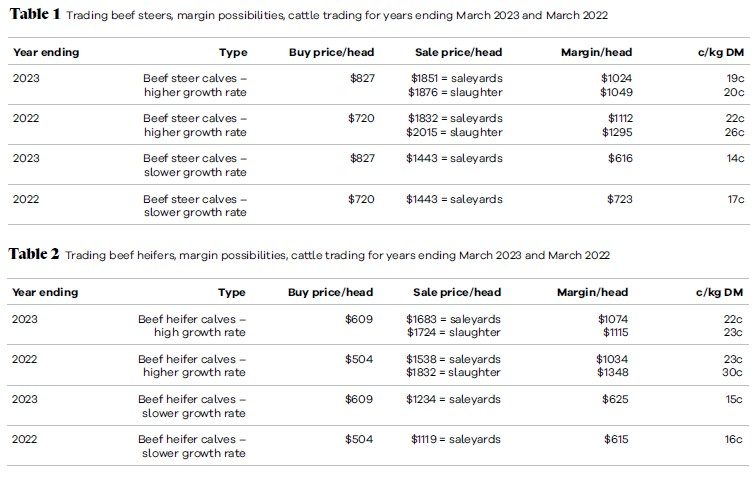

As a simple trade, let’s look at buying a pen of Angus-Hereford steer calves at one of the Temuka calf sales, say on April 4, 2022, and selling them a year later on March 23. They are average calves, weighing 233kg liveweight (LW) and cost $827/head in 2022 compared to $720/head a year earlier in 2021.

If these were grown at a high growth rate of 1.13kg LW gain/day they would weigh 630kg on March 23, 2023. At that weight they are classed as finished, so could be sold either at the Temuka prime sale or direct to a processor. Because there is often a slight difference between these markets due to factors such as availability of processing space, I have compared the two options.

Note that the prices used are gross with no costs taken off, because they will vary with your own individual circumstances. Also, I have used a generic average available processor price without any premiums that might be available on specific contracts.

As a comparison, if you fed the steers less quantity or quality feed they will have grown at a lesser rate. Say we use 0.75kg LW gain/day for the year you had them, then instead of hitting a slaughter weight, they get to 500kg LW, which is more likely, meaning a store sale for them. While they could still be sold for processing, their yield will be less than at a heavier weight and they might just slip down a price tier at a lighter weight. So we say they have been sold back at the Temuka sale as stores.

Table 1 shows the comparative results for the various options for both a trade over the 2022/23 year and the 2021/22 year.

The purchase price for the steer calves was $3.09/kg LW in 2021, rising to $3.55/kg in 2022. That reflected the good margins that had been made with the earlier trade, which buyers passed back to breeders at the calf sales. And having the optimistic gene, the buyers hoped the good times would continue.

The sale price from processors sat at $5.80/kg carcaseweight (CW) in March 2022, reducing to $5.40/kg in March 2023. Given the doom and gloom prevalent in the world, that drop of about 7% is mild compared to the $1.50/kg CW fall in lamb schedules in the same timeframe. At close to a 20% fall, it has ripped the profitability out of many sheep farming businesses.

Putting the higher price and the lower sale price together has obviously reduced the margin for profit – by $88/head if selling at the saleyards and $246/head if selling direct to processors. At more than $1000/head margin for a 12-month trade, that remains at the higher end of historically achievable levels.

Note the larger difference between saleyard and processor price in 2022 for the heavy steers compared with 2023. Slaughter space was tighter a year ago than now, which gave a discount to saleyard price.

The margin per kg DM has reduced proportionately between 2022 and 2023.

The other option was to grow the steers at a slower rate and sell them store at the Temuka saleyards at the same end of March timeframe. For a third less growth rate, the potential profitability reduces accordingly.

The moral of the story is that when margins get tighter, the most efficient producers can still make headway.

Beef weaner heifers

Instead of buying the Angus-Hereford steer calves, we might have purchased their sisters at a lighter liveweight of 210kg at a lower price. We were looking at $2.40/kg in April 2021 compared to $2.90/kg in April 2022.

The heifers will not grow quite as fast as steers, so I have picked a higher growth rate of 1.05kg/day and a slower rate of 0.7kg/day for comparisons. The higher growth rate heifers could be sold prime at 580kg LW at either the saleyards or direct to slaughter, with the slower growing animals getting to 457kg, to be sold store at saleyards.

Table 2 shows the possible margins for these heifers. Note the margin a head is not dissimilar to the steers over the same time frames. And the margin per kg DM is similar or possibly higher than that of the steers. Again, the higher buying prices and lower selling prices for the 2022/23 trade have impacted the margins.

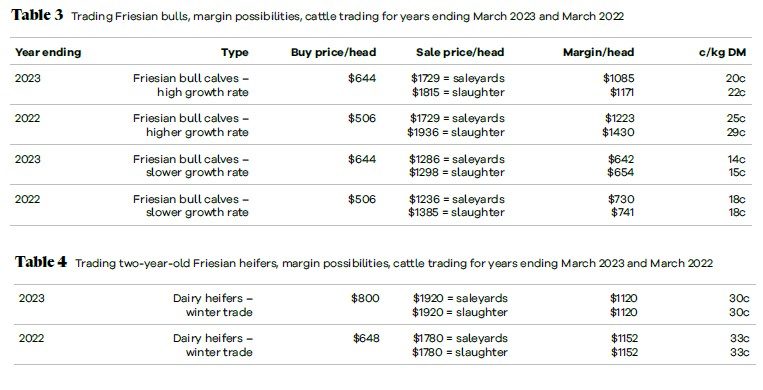

Friesian bull calves

The next option looked at last year was buying Friesian bull calves at Temuka saleyards for a comparable time trade. I used the figures of buying a 230kg bull calf, growing at either 1.13kg/day or 0.75kg/day. The resulting sale weights would be either 629kg LW or 495kg.

The slower growth rate bulls could be sold back to the saleyards or to processors, but as with the steers, there is risk of the lighter animals slipping below a price tier at processors.

The figures for the Friesian bulls are not dissimilar to the beef steers and heifers. A good growth rate will have resulted in more than $1000/head margin and more than 20c/kg DM achieved. A slower growth rate drops that by about a third. The margins dropped in the 2022/23 trade compared to the previous year.

R2yo dairy heifers

The other trade I compared was buying rising two-year-old Friesian heifers in April. They had been scanned empty from dairy herds and had the frame to be grown into prime beef for slaughter late October. This is a shorter trade than the previous three options. We could look at R2yo beef steers or heifers of a similar age, but I have used the dairy heifers because they are generally considered the least desirable beef option and are frowned upon by many.

Assuming these were reasonably well-bred Friesians, they could have been wintered then sold seven months later at the end of October having grown at 0.9kg/ day to achieve 600kg LW. The selling options are to sell back in saleyards as prime or direct to processors.

Table 4 shows the results possible for the dairy heifer trade. Selling prime in October 2022 had a sale price of $6.40/kg CW, rising from $6.00/kg in October 2021. That gave a similar margin to both years due to the purchase price rising in April 2022. The margin per head that could be achieved in seven months was similar to that over the 12-month trade for younger animals, giving a higher return per kg DM input. It is a different trade and brings some implications for wintering heavier cattle and not using all the spring pasture growth. The store cattle buyers generally show a preference for short-term trades, which is reflected in their purchase price levels.

Summary

Cattle purchase prices were generally higher in 2022 than 2021 and we saw a fall-off in processor pricing in late 2022, which has impacted per head margins.

Note that the margins shown are gross, being sale price less purchase price. Net profit depends on your own individual costs of transport, selling and feeding. Feeding costs can vary considerably depending on how you winter your animals. For example, all-grass wintering may be costed at close to $100/head while feeding a brassica/balage mix might be more than $300/ head.

While prices vary between and within years, profitable beef production is based on getting the optimum growth rate relative to your cost structure. Purchase price is one part of profitable beef trading, as is sale price and growth rates achieved.