BY: ANNABELLE LATZ

Positive discussions have taken place between the Department of Conservation (DOC) and the Game Animal Council (GAC) regarding the current aerial tahr control programme, resulting in changes to control work outside Aoraki/Mt Cook and Westland/Te Poutini National Parks.

In July, DOC was ordered by the High Court to undertake only 125 aerial control hours of the proposed 250 hours under the Tahr Control Operational Plan for 2020/21 before undertaking further consultation. DOC was also requested to analyse oral and written submissions from stakeholders involved in the Tahr Plan Implementation Liaison Group (TPILG), before making its decision and releasing its final Operational Plan.

The TPILG includes representatives from the hunting sector, Ngai Tahu, ecology, conservation, research, high country farmers, tramping fraternity, meat processing industry, and government bodies.

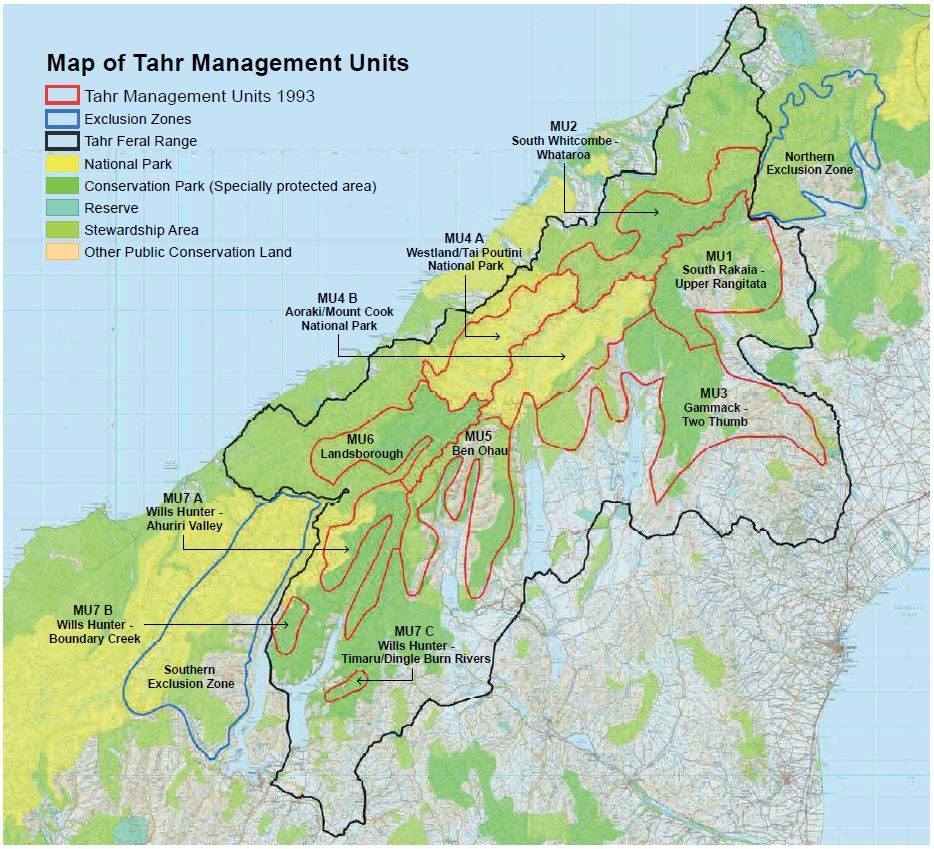

The management of Himalayan tahr is governed by DOC’s statutory plan, the Himalayan Thar Control Plan 1993, that stipulates the tahr population is to be monitored and limited in their South Island range which includes Aoraki/Mt Cook and Westland/Te Poutini National Parks. In total, this area is 706,000ha, divided up into seven tahr management units.

On September 1 DOC announced the distribution of its remaining 125 hours of aerial control outside the national parks would remain largely as per the original plan.

The tahr hunting sector remained disappointed and concerned that DOC’s estimated population numbers were too high, population research was out of date, and aerial control was being targeted to the wrong areas thus effectively eliminating the tahr population for hunters in some places.

“It’s really sad, as there’s so much common ground between stakeholders with 90% of the recent submissions all on the same page,” said Tahr Foundation spokesperson Willie Duley.

On September, 8 DOC met with the Game Animal Council (GAC) to discuss where the remaining 77 hours of control work outside the two national parks would be undertaken. Following plenty of discussion, it was agreed to reallocate some of the control hours to target less accessible areas of the feral range, and keep the more accessible areas for hunters.

“We are reducing our previously planned control hours within the South Rakaia and Upper Rangitata management unit which is favoured by hunters,” DOC’s Operational Director Dr Ben Reddiex said.

DOC agreed to avoid popular hunting spots and huts, focus on controlling high densities of tahr within terrain that is less suitable for ground hunting. It would leave identifiable male tahr for hunters outside of the national parks’ management unit, improve hunter access by extending the popular tahr ballot. The latest control data is regularly updated on DOC’s website.

GAC general manager Tim Gale was satisfied with the result of the discussions, and this is what the tahr hunting sector wanted all along – an open discussion and to have all the information on the table.

“Everyone has always agreed that tahr do need managing, it’s about how much, how many tahr, by whom, and where. It’s about the quantum of control.”

GAC mapped out areas and suggested places where recreational hunters were unable to access and official control should target, as opposed to ballot landing sites and really popular hunting areas.

“It was a two-way, free and frank discussion about the pros and cons of the current allocation of hours within the Management Units, and the merits of reallocating hours,” Gale said.

The outcome was positive, which now means DOC is still getting the tahr control they wanted, and the tahr hunting sector can continue to hunt in the popular and accessible areas.

Gale said the potential risk lies in the coming year, the drop in breeding due to the number of juveniles and nannies that have been targeted by recent control programmes.

“The bulls will start to die of natural mortality, or get shot, and with reduced recruitment, the population may just fall off the cliff in some places.”

In mid October DOC held a meeting with the TPILG to discuss a Research and Monitoring Strategy in order to help identify priorities for tahr research and monitoring.

“There are questions we need to be asking in the research. How many tahr the habitat can handle, how many tahr and what types of tahr hunters need to have a good experience. It’s about tahr population impacts and ecology, understanding hunting, knowing how many bulls there are compared to nannies and what will happen with future herd structure. Also, how this research takes place, when, and who does it,” Gale said before the meeting.

Duley sees very little concession, as the same amount of culling hours still stand and DOC continues to target the highly prized bull tahr in national parks.

He is also nervous about the damage being done to the tahr herd structure by DOC’s annihilation of the breeding nanny population as well as the juveniles, of which 50% will be males.

“We will see the real damage in the years to come, there won’t be those young bull replacements and as soon as the old bulls die off, there will be some massive age gaps. This won’t help when the tourist hunters come back looking for a trophy bull.”

Duley says it’s a case of ‘too little too late’ for DOC’s decision to back out early from some of the management units and they should have listened to the industry’s advice on where culling was needed from the word go.

“We’re on the ground, we know the tahr hot spots but they ignored us”.

“They have already culled those units in round one, so the damage is already done. It’s only logical that they would now focus on the more inaccessible areas with higher populations. It’s just really sad, this whole process could have been managed so much better by DOC, without all the conflict. I’m deeply concerned about what future lies ahead for the tahr and all hunting communities around the country.”

James Cagney, Professional Hunting Guides Association president, says the $103 million commercial hunting industry must be protected.

At least 95% of those hunters are from outside our borders, and of that, 82% are from the United States.

Cagney adds that 20% of that international market is tahr driven, as NZ is the only readily accessible tahr hunting destination in the world. Hunters capitalise on this, usually hunting for red stags too.

If the tahr hunting option was removed, hunters would most likely choose a destination closer to their own homes to hunt for red stags.

“The big factor with tahr is they are a really big drawcard for overseas hunters. The value of the tahr herd to the hunting industry is greater than the revenue generated by tahr.”

Cagney is concerned DOC is launching into the culling programme without pausing to assess the numbers of tahr currently out there.

“We have a male-bias herd, the proposed culling could reduce the breeding population to as low as 2000 females.”

He says in the last three years more than 18,000 tahr have been killed, and DOC’s failure to pause and assess numbers has caused genuine fear amongst the hunting community.

“The 1993 Plan talks about a number of 10,000, but wasn’t hard and fast. It’s time to pause, do some monitoring, establish where the herd is currently, and propose what the population will look like afterwards.”

Cagney explains the required research really has two basic stages. The first is to establish how many there are, get a gauge of the demographic and male/female densities. The second is getting into the nuts and bolts, scientifically assessing the impact on vegetation and how many tahr specific areas can sustain.

“The hunting sector values our biodiversity just as much as the conservationists do. But we believe with science and proper management, we can have positive outcomes for both.”

‘Everyone has always agreed that tahr do need managing, it’s about how much, how many tahr, by whom, and where. It’s about the quantum of control.’

Pendulum needs to swing back

The Himalayan Tahr Plan from 1993 sits on the shelf in Dr David Norton’s office in the Forestry Department at the University of Canterbury gathering dust.

“I say to my students, there is no point creating something that is going to sit on the shelf and gather dust, it has to be something you reference and use regularly.”

Norton is a Professor in Ecology and Conservation Biology, and someone who has been knocking around in the mountains for the past 40-odd years, and also an expert on forest and alpine systems, and holds a thorough understanding of the partnership between land users, hunters, and the environment.

As herbivores and mob animals, tahr eat grasses, herbs, shrubs, tussocks, forest seedlings, and in turn can change tall tussock grassland to short tussock grassland.

“They also eat large palatable herbs, and enjoy soft palatable food like buttercups, including the Mt Cook Buttercup.”

“Population density should have been managed over the years since the plan was written in 1993, and vegetation monitoring plots measured regularly, and DOC should have been working with hunters the whole time, but these things haven’t happened.”

Norton shares Gale’s view that there has been some really good progress recently between DOC and stakeholders, but these conversations need to lead to further change.

“I guess my hope and wish is that the communication between DOC and GAC evolves into the development of a new version of the tahr control plan and to its ongoing implementation. I really believe that only through true collaboration will we be able to get a sustainable solution that meets both conservation and hunter interests.”

Norton was left feeling more optimistic after recent conversations with DOC, but it is always a worry of his when politics gets in the way of sensible resource management decision making.

“The pendulum needs to swing back again. We all need to sit down together and work out how to move forward with managing tahr in a collaborative manner.”

He acknowledges DOC has not had the funding to put their required resources into the plan, but the two fundamental problems of lack of tahr population management and lack of communication needs to be sorted out.

“The blame doesn’t lie with any one community. But there needs to be a rational discussion about how many animals are out there and what their impacts are at different densities and in different areas, so let’s get some good science in there, and figure out a sustainable management solution together.”