Tony Alexander

The world is facing its biggest recession since the 1930s Great Depression. Governments are undertaking huge spending increases, central banks are printing money, and global trade is badly interrupted. One could be forgiven for thinking that the next few years will be exceptionally bad, especially for a country like New Zealand where international tourism accounts for 5.5% of GDP versus 3% on average around the world.

Yet the answer as to why the downturn is likely to be relatively short lived lies partly in the information above. Our Government is boosting spending equivalent to 20% of GDP. We have never seen such a surge and it will go a long way towards insulating the economy against the obvious effects of the Covid-19 virus.

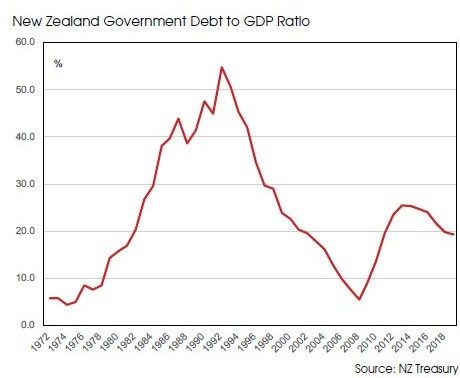

But will this surge in spending, which will push the government’s net debt-to-GDP ratio to 54% in three years from 20% a few months ago, necessitate higher taxes to pay for it in future years? No. The ratio was 5% in 1972, hit 55% in 1992, then fell to only 8% ahead of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008.

This decline to 8% was not achieved by raising taxes (Michael Cullen’s unnecessary 39% income tax rate notwithstanding) but by exercising good control over government spending. The same thing is likely to happen again, and it is unlikely the ratio will ever be taken back down to 6%. Treasury is projecting 40% in the mid-2030s without any tax increases.

Plus it pays to note that, even at the predicted peak of 54%, the net debt-to-GDP ratio will still be below pre-virus ratios in the United States, Europe, Japan, and the UK.

Another reason for anticipating better economic conditions over 2021 is the arrival of money printing in New Zealand. Other countries engaged in this after the 2008-09 GFC and did not see their inflation rates rise. Instead, most of the money remained in bank accounts providing easy funding for banks. But some went into assets offering higher yields than bank deposits, including property and shares.

It is highly likely – and the Reserve Bank has admitted this risk – that money printing will push up property prices in New Zealand including, eventually, farm land. The sharp rise in consumer trust of New Zealand’s food products offshore is boosting interest in farm assets, especially from investors looking at very low yields on other forms of property and facing new worries about tenants ability to pay and to remain in occupancy.

With regard to interest rates, they were at record lows heading into this recession, have gone even lower, and are unlikely to go up to any appreciable degree for many years. This after all has been the experience of other countries following recovery from the GFC.

At issue, however, as some investors look to buy assets like property, is the availability of bank credit. For probably the remainder of this year banks will have very tight lending criteria. It is not just that they will suffer some big losses from the intensity of pressure this recession is imposing on the tourism and hospitality sectors in particular. Banks legally have to undertake responsible lending – not extending credit to borrowers they feel may have difficulties servicing or repaying a debt.

Banks are struggling to model what the future looks like for the overall economy, let alone individual sectors. So they have raised minimum deposit requirements and, in many instances, have no interest in taking on board new business clients – especially those involved in property development.

However, banks make their money from lending money and eventually will reopen their lending books. That probably won’t happen until next year for most sectors of the economy apart from housing, for which they may allow pass-through of the recent removal of Loan to Value Ratio rules (LVRs) before the end of the year.

What about the world growth outlook? It is hard to know how exactly to write this but it increasingly looks like many countries have decided that if a second wave of virus outbreaks strikes they will not close their economies down again. For the moment they are continuing to work on boosting their healthcare sectors to handle as best they can a new outbreak should one come along.

This doesn’t mean a global recovery is imminent but improving conditions over 2021 are likely, especially if a vaccine against Covid-19 is developed.

For farmers this means that, over the next 12 months, risks for commodity prices probably lie on the downside. But with New Zealand’s reputation seemingly rising by the day our long-term primary sector outlook is actually better than it was four months ago – and that is the sort of thing investors will think about as they look at potential purchase of farming assets.

- Tony Alexander is an independent economist who was the BNZ’s chief economist for 25 years.