From banking billions to dairying dream

Once in charge of US$1 billion daily in international currency markets, Charlotte Aitken swapped the rat race for milking cows on the West Coast. Words Anne Hardie, Photos Jules Anderson.

Waves pound the wild beach beside Charlotte Aitken’s farm she owns with her husband, Murray. The remote and rugged location is as far up the West Coast past Karamea as you can drive, and a world away from the London business scene of “suits and boots” that was once her territory.

Waves pound the wild beach beside Charlotte Aitken’s farm she owns with her husband, Murray. The remote and rugged location is as far up the West Coast past Karamea as you can drive, and a world away from the London business scene of “suits and boots” that was once her territory.

Her eye for figures has helped her West Coast dairy farm rank in the top 10 percent for regional profitability.

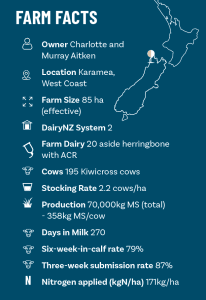

These days, the 61-year-old milks 195 Kiwicross cows on 85 effective hectares, producing about 70,000kgs milksolids with low inputs and tight control of expenses. And she’s loving it – working with cows, living in a small community and attending her weekly “counselling” session at the Karamea Hotel.

Raised on a sheep and beef farm at Dovedale in Tasman, Charlotte worked her way from the post office – where she “licked stamps” alongside Murray – into banking, eventually landing at the United Bank of Kuwait in London.

Their two children were born in London, at a time when Charlotte was working with foreign exchange and money market settlements – moving around US$1 billion a day. When overdraft rates soared past 100 percent, she “got to know a lot of people in the bank that day”.

It was a time where she learnt about negative equity. They lost money on a London flat, but many young homeowners fared worse, handing their keys back to the bank.

In 2000, they decided to return home with the kids. Charlotte worked with equities and bonds for a while until she’d had enough and decided she needed a change.

“I decided I knew where bullshit came from and went and knocked on a door at a dairy farm and said I wanted to be a dairy farmer. So can I come and work for you for free?”

She worked unpaid for two months on a Wairarapa dairy farm and knew she’d found her path. Murray and the kids were living in Upper Hutt, where he worked in the army’s accounts department, and every fortnight Charlotte would head home.

She still has a scrap of paper from her early days dairying that has a plan to be 2IC, manager and then own a farm within five years. She more or less followed that plan, although chose to remain a farm assistant because she enjoyed the role.

That made it more difficult when they went to the bank to buy a dairy farm, because she says job titles matter to banks and being a dairy assistant didn’t cut it.

“We had the money and everything there, but because I didn’t have a title, we had to find another 80K (equity) to buy the place.”

They had looked in Wairarapa for a farm to buy, but at $50,000 or so a hectare, it wasn’t an option. Whereas on the West Coast of the South Island, they were looking at $16,000-$17,000 a hectare, purchasing a property that wasn’t on the market at the time.

“One lesson I carried into dairying from foreign exchange trading is that you can always lose money!”

She was in her mid-50s by the time she milked her own herd and some people questioned her age for such a venture. But her view has always been: “Don’t tell me I can’t do something”. Her grit has seen her complete the Tāupo Ironman in 2013 – a 3.8k m swim, a 180 km bike and a 42 km marathon – and a few half marathons as well. Buying a dairy farm in her mid-50s was pretty much business as usual.

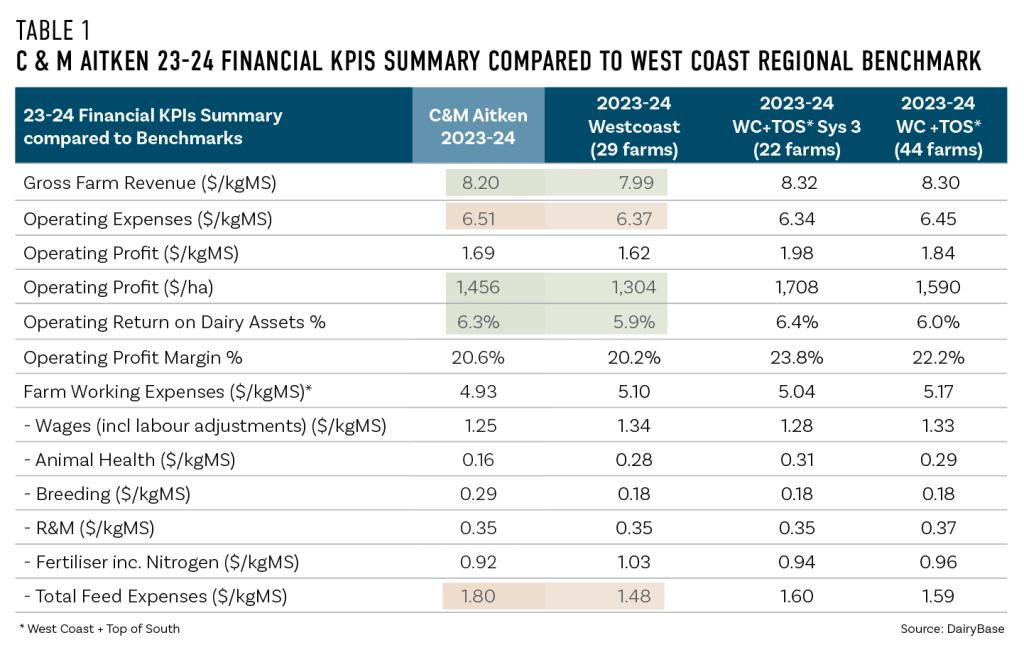

Just like her banking days, the figures count. The most recent figures available for the farm are from the 23-24 season, where her farm working expenses were $4.93/kg MS and her operating profit was $1.69/kg MS and $1,456/ha. That was $150/ha above DairyNZ’s DairyBase benchmark analysis for 29 West Coast farms.

Six years after buying the farm, Charlotte is considering her next move. The original 10-year-plan had been to sell after five years, but she reckons she “has another couple of years in me” before their son returns from overseas. She hopes he will continue dairying, build equity and buy out his sister’s share.

“One lesson I carried into dairying from foreign exchange trading is that you can always lose money!” – Charlotte Aitken, Karamea, West Coast

In Karamea, Murray works off-farm but helps out with jobs like milking or fertiliser when needed. Charlotte says dairying just isn’t his thing, but he loves the golf, bowls and socials of the small community. Apart from employing someone through spring, she runs the farm by herself.

It’s a simple, flexible system on the farm. Through spring, the cows are milked twice a day until the unirrigated farm begins to dry out. Then she drops to either 3-in-2, or even 10-in-7 milkings which she really enjoys. Last year she dropped to once a day in January. It’s all about being flexible and depends on “what the weather chucks at me” or the unexpected.

“The whole herd got facial eczema last March and production went out the back door pretty quickly. I knew there was something wrong because I was cupping a cow and she kicked them off and I went to put them back on and she got her foot up over the rail and kicked me in the face. So I had to dry off a fair few of them and lost one.”

Summer is the main challenge. Sandy soils near the coast dry out easily, whereas plateaus on the farm have pakihi soils which have been flipped in the past. In between are humped and hollowed paddocks and it all dries out in summer. “In summer, once it disappears, it’s gone.”

Lucerne is the only green on the farm in summer and she gets four cuts of balage from it, followed by one or two grazings. Between the farm and another property that grazes half the herd in winter, she makes about 200 bales of balage to feed out through summer.

During wet weather or if cow condition starts dropping off, she adds palm kernel into the system at a rate of 1-2 kg per cow per day in a trough beside the dairy. It’s simple and low cost compared with other inputs, especially with freight costs to Karamea.

“The cheapest food you can put into a cow to keep their condition on is PK, if you have to buy in supplements. I vowed and declared I’d never use it, but in summer when there’s no grass, it does keep condition on them.”

She once tried a turnip crop for summer without success, so sticks with lucerne and balage. Winter is easier as the grass keeps growing and she can grow a crop. About 4ha of rape is sown each year to help winter half the herd.

Though she doesn’t like spending money, she plans to invest in Halter technology to enable her to graze the farm differently. “Once I’ve slowly moved to virtual fencing, I won’t have to replace fences that rust in the salt air.”

“Once I’ve slowly moved to virtual fencing, I won’t have to replace fences that rust in the salt air.” – Charlotte Aitken, Karamea, West Coast

“You still need boundaries, laneways and gateways so your cows don’t keep thinking they can go into a paddock if there’s nothing along the laneway. And you will be able to back fence which then gives that grass time to grow.”

Along with pasture management, she’s looking forward to Halter’s information on cow health and mating.

For mating, she uses FlashMate heat detectors which have worked well through the years and improved in-calf rates. Back in the 22-23 season, 72 percent of the herd was in calf within six weeks, and the empty rate ended up 18 percent. During the 2024-25 season, the six-week in-calf rate had lifted to 79 percent, and the empty rate was down to 13 percent.

For the first four weeks of mating, cows are artificially inseminated, followed by four weeks with bulls – bulls she breeds and sells locally as four-day-old calves.

Those bulls are the result of DNA testing which helps her reduce the number of bobbies. This year she had just 29 bobbies out of 205 calves, achieved through a multi-pronged approach.

As well as selling four-day-old calves to locals to raise for beef, she keeps about 20 AI Kiwicross bull calves that she gets DNA tested. High BW bull calves are selected and six eventually go over her heifers. She can then keep heifer calves from her heifers because the bulls are DNA tested, reducing the number of calves from her heifers ending up on the bobby truck.

The Kiwicross bulls head to her brother’s farm in Dovedale to finish and are used over Charlotte’s carryover cows along the way.“I don’t like waste! If I have cows that are not in calf and they’re young enough (up to five years old), I hold on to them and send them to my brother for a year, so they have to go and climb around the hills, so they don’t come back fat. He’s got my bulls that I’ve DNA’d, so that when they come back and have a heifer calf, I can keep that as well. Too many young heads are chopped off.”

One of the local couples who buys the beef calves provide two-year-old bulls for Charlotte to use in the final four weeks of mating.

“When I arrived here, I got some bulls in and they were doing okay, but you usually have to take the bulls about two weeks before you need them. So, you’ve got them on your property, trying to find somewhere for them to keep them out of the cows.”

Now the bulls arrive exactly when she needs them and four weeks later, they are collected and taken away.

While that deals with beef-cross calves and some of the bull calves, Charlotte also maximises her heifer calves. Forty heifers are kept as replacements and a further 18 are raised and sold in January.

Another income stream comes from the nikau palms that grow prolifically in the region, including the bush that still covers the side of the terrace on the farm. At about three metres tall, they are dug up, wrapped and transported to places like Auckland’s CBD.

For time out, Charlotte strolls over to the beach to surf cast with her drone – labelled with her phone number and ‘please return’ message in case of pilot error. She has recovered the drone in a paddock before, covered with cow dung.

“I entertain people at the pub with my skills! I don’t catch a lot of fish. But it’s a nice place to sit. There’s a couple of older guys out there with Kontikis, so I always make sure I have two beers for them if it’s the right time and they’ll come down and have a beer. If I don’t catch anything, I get filleted fish!”