Feed ’em like dairy cows

The sheep industry’s success in breeding more-fecund ewes has put a lot of pressure on our pastoral system to provide enough quality feed, Russell Priest reports.

The sheep industry’s success in breeding more-fecund ewes has put a lot of pressure on our pastoral system to provide enough quality feed, Russell Priest reports.

If farmers want to maximise lamb production they need to start feeding the ewes more like dairy cows.

That’s what Professor Paul Kenyon of Massey University told a Beef + Lamb NZ Farming for Profit seminar at Rangiwahia in northern Manawatu recently.

He said the most efficiently produced prime lamb is one which is drafted off mum. The weight of that lamb is largely generated by the most nutritious feed the lamb is ever going to get, its mother’s milk.

Kenyon said there was at least a 30% difference (1 litre/day) in milk production between ewes with a Body condition score (BCS) 4 and BCS 1 being underfed at the same level of 1.8kg DM/day.

His presentation was on managing ewes and hoggets in winter through to set stocking.

Kenyon says more-fecund ewes has put a lot of pressure on the pastoral system to provide enough quality feed for them, particularly in the last month, of pregnancy to maximise their production potential.

Ewes bearing multiple pregnancies struggle to physically eat enough of the bulky (low energy dense) feeds like grass and brassicas to satisfy their energy requirements in late pregnancy. The uterus with its rapidly growing foetuses pushes up into the rib cage and reduces the size of the rumen .

“That’s why having a fat buffer generated by having a BCS greater than three to get them through this period is essential.”

Grass is 80% water so during the last month of pregnancy a multiple-bearing ewe needs to eat and ruminate 25kg a day to meet her energy demand which is a tall order especially if her teeth are suspect.

Swedes are even worse at 92% moisture so should never be fed to multiple-bearing ewes in the last month of pregnancy because there’s not enough energy in them.

Underfeeding and/or poor body condition of in-lamb ewes can lead to an alarming number of problems including increased lamb mortality.

He says unfortunately farmers never seem to have enough grass to achieve the ideal levels of feeding particularly in the last month of pregnancy mainly because of the timing of lambing and winter feed growth.

“The ewe flock should not be managed during pregnancy as just one group. Differential feeding is required.”

This should be based on a ewes BCS, the number of foetuses she is carrying and her expected lambing date (i.e. early or late).

The lower the BCS below 3-3.5 the greater will be the production response to better feeding.

He says BCS in mid-pregnancy to identify the bottom 15-20% then set stocking and preferentially feeding these will greatly improve their performance.

Set up a feed budget

Information on pasture covers based on historical data is invaluable in setting up a feed budget. If this shows a deficit particularly during the late winter/early spring a plan should be developed to prioritise which stock will be apportioned the scarce feed.

He suggested prioritised feeding should be first given to poor-conditioned, multiple-bearing ewes lambing in the first cycle. Next the rest of the first cycle multiples. Second-cycle multiples should be third followed by first-cycle single-bearing ewes and finally late-lambing singles.

Single-bearing ewes are more able to buffer and the feed demand of later-lambing ewes will increase in line with increasing pasture growth.

Triplet-bearing ewes have theoretically a greater feed demand than twin-bearing however the issue is that they can’t physically eat more than the latter. Kenyon’s advice is that if there is plenty of feed (above 1200kg DM/ha – 4cm) triplets need not be separated from twins.

He says triplets feed demand becomes greater than twins about six weeks before lambing. If feed is scarce they should be offered paddocks in which covers are greater than 1200kg DM/ha.

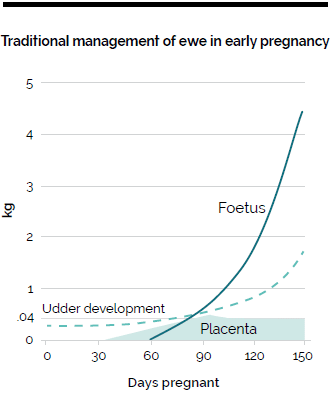

Energy requirements of a pregnant ewe are relatively small until scanning (day 90 of pregnancy) during which time the placenta, foetus and udder are developing. Developing a large placenta is critical in supporting multiple pregnancies. At scanning the foetal growth starts to increase significantly until day 120 when it starts to accelerate.

When a ewe lambs, it sheds a significant amount of weight in the lamb, associated fluids and placenta etc (single lamb 10-13kg, twins 14-18kg, triplets 20-22kg). So if she is to maintain her mating weight she must increase it during pregnancy by these amounts especially in the last month.

Kenyon says during days 100 to 132 of pregnancy not to graze pastures below 900kg/ha. In the final two-three weeks before lambing, ewes should be offered an allowance of 2.5-4kg DM/ewe/day. Intake should not be restricted and pastures should not be grazed below 1200kg DM/ha (4cm).

Ideal covers for any productive sheep are 1200-1800kg DM/ha because at that level they are able to get a full mouthful each bite. Sheep can only achieve a fixed number of bites a day because they also have to ruminate.

Optimal grazing covers at lambing are 1400kg DM/ha. Don’t offer more than 1800kg DM/ha because they’ll trample it into the ground and quality lost later on in the spring.

Farmers know from experience which are the best paddocks for twin-lamb survival.

Kenyon advises that these paddocks are given time to recover after grazing for the best possible covers when set stocked for lambing.

Individual paddocks should be set stocked according to ewe demand (number of pregnancies, BCS), pasture cover, lambing cycle (early/late lambers) and lamb survival rating. Thinner twin-bearers should be set stocked at a lower rate. Later lambing ewes can be offered less feed than earlier lambing ones. Paddocks with poorer lamb survival records can be stocked with singles or even better conditioned twins.

Impact of ewe deaths

Ewe deaths during the lambing period were often underestimated and can have a huge impact.

He says 50% of ewe deaths occur between set-stocking and docking.

If a death rate in a flock of 1000 is 10%, it can be an expensive exercise. If these ewes recorded a 150% scanning and 5% (50) of these ewes died between set-stocking and docking this represents a potential loss of 75 lambs. Not only does this represent a loss of income from the lambs, but it also means the farmer must find another 50 replacements.

These replacements may come in the form of hoggets, two-tooths or mixed-age ewes with the latter being a better option for the average farmer.

He says a mature ewe can be held at maintenance for at least two thirds of her pregnancy because she has reached her mature weight.

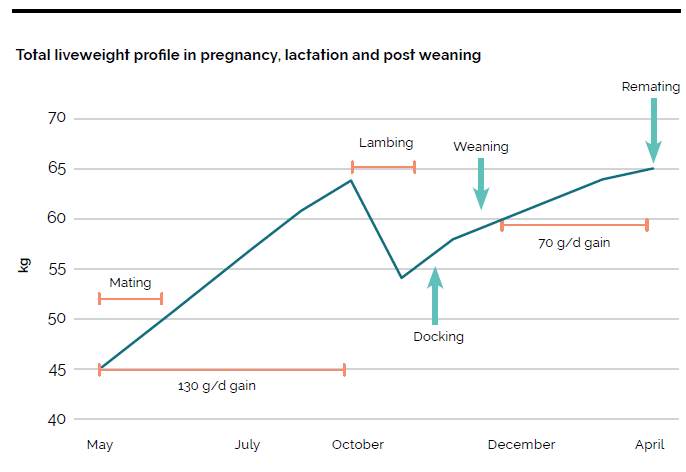

A mature ewe only has to put on a maximum of 22kg during her pregnancy if she is bearing triplets to maintain her mating weight whereas a 45kg hogget has to grow at 130g/day, wean a lamb plus grow a further 90g/day from lambing through to re-mating at 65kg.

“This is the ideal growth profile of a hogget to avoid her two-tooth weight and her lifetime productivity and longevity being compromised.”

To achieve this she needs to be offered good quality herbage with pre-grazing masses in the range of 1400-1800kg DM/ha and post-grazing masses above 1000-1200kg DM/ha. This may require a reduction in other stock classes or an increase in alternative feed sources like brassicas or chicory, plantain or clover.

Winter crops can be used in early to mid-pregnancy, however hoggets should not be asked to clean up a paddock as this will restrict intake. The aim should be to grow them as big as possible.

Energy demands

The first two thirds of a hogget’s pregnancy is the period in which the energy demands from the conceptus are low. This is the most opportune period for the hogget to grow so that she develops good structural size. It is not the time to be rationing her feed intake and stunting her growth.

“Farmers concerned about lambing problems in their hoggets are shooting themselves in the foot by screwing them down during pregnancy. This slows their growth and development of structural size and since this is directly related to pelvic area this creates lambing problems having the opposite effect to what was intended,” Kenyon said.

He explained the reason why birthweight cannot be significantly influenced by feeding is because 90% of a lamb’s birth weight is determined at conception with only 10% being influenced by feeding. The foetus is like a parasite and the ewe/hogget will do everything within her power to keep the foetus alive, apportioning as much of her energy as is necessary into retaining it often at her own expense (death). This is known as the buffering effect.

He says Massey conducted a trial where 40kg hoggets were mated to the same rams and grown three different growth rates to reach 60, 70 and 80kg before lambing. All lambs were weighed at birth with the average weight of the lambs from the 80kg hoggets being only 300g heavier than those from the 60kg hoggets.

“Of course the 80kg hoggets spat their lambs out easily.”

Rams from breeds of a lower mature weight than the hogget breed are the best for mating hoggets.

A large study looking at the relationship between lamb survival and weight of hoggets at lambing showed at 50kg the lamb survival rate was 66% and 88% if 60kg.

With hoggets lambing in late September the pasture covers should be improving and at least 1200kg DM/ha. The aim is to feed hoggets as well as possible to not only achieve maximum milk production but also to encourage them to continue to grow.

As with the ewes if pasture covers are lower than is ideal, hogget mobs need to be prioritised.

Herb mixes have been shown to increase lamb survival and weaning weight as well as hoggets lactation performance, liveweight and BCS.