Farming on the edge

A couple have some extraordinary challenges building a productive breeding herd next to the ocean. Mike Bland paid them a visit to find out more.

Rob Craw and Amelia Hodder have spent 10 years building a productive breeding herd on a scenic but challenging farm on the southern shores of the Hauraki Gulf.

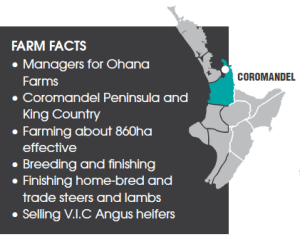

They’ve been on the 337ha (effective) Coromandel Peninsula farm, just south of Coromandel township, since 2011 and manage it for an overseas-based family trust. Under the Ohana Farms brand, they also oversee another sheep and beef unit near Te Kuiti in King Country.

From the Coromandel farm’s homestead they can watch fishing vessels and pleasure boats heading out to the Gulf. Amelia says the farm is highly visible from the sea, so they try to be the best advert for farming they can be.

She and Rob and their three sons moved to Coromandel after leaving a management position on a large King Country sheep and beef farm.

Rob says they were enjoying the King Country job and it was a tough call to move. But the Coromandel farm presented a great opportunity and the coastal location was a big drawcard, especially for Rob, a keen fisherman.

“The irony is; I probably did more fishing when I was in the King Country.”

Rob and Amelia have both involved themselves in the local community. Rob is a senior member of the Coromandel Volunteer Fire Brigade and president of the Hauraki-Coromandel branch of Federated Farms. Amelia is the branch’s provincial support person.

Their twin sons Dylan and Ryan, aged 15, attend Coromandel Area School and oldest son Cody, 18, recently completed a diploma at Telford and is now working as a shepherd in Central Otago.

Their twin sons Dylan and Ryan, aged 15, attend Coromandel Area School and oldest son Cody, 18, recently completed a diploma at Telford and is now working as a shepherd in Central Otago.

Rob was quite surprised to get the Coromandel job because during the interview process he was frank about the property’s limitations.

The farm’s location on the coast exposes it to winds that dry it out quickly in summer. Its shallow topsoil sits on a layer of marine clay, and the pastures are dominated by kikuyu. The farm also has a number of steep bluffs, which can be a hazard for livestock.

He told the owners it had potential as a breeding unit, but dry summers and a lack of suitable contour meant it would struggle as a finishing block under an all-grass system.

“It was simply not sustainable on its own.”

The new owners appreciated his honesty.

“Up until meeting the owners I’d been a bit wary of foreign ownership. But they were clearly very passionate about the farm and we shared the goal of wanting to produce high quality protein products as sustainably and ethically as possible.”

Amelia says about half of the grazeable area is steep, 30% is medium hill and the balance is easy-rolling.

She says a drought in their first season on the farm gave a real taste of how difficult coastal farming could be.

Running two farms

The first few years were particularly busy as Rob sought to secure and set up a second farm to complement the Coromandel property.

“The owners asked us to go out and buy a block with easier contour and better summer growth, and we hunted high and low to find somewhere that ticked all the boxes,” he says.

Bought in 2012, the King Country farm had a good balance of easy-rolling contour and some steeper hills. It totalled about 1000ha, of which about 520ha is effective. The balance is mostly in native bush, “and that’s a feature the owners really liked”.

Rob says the buying process took a long time due to OIO requirements.

“The owners had to be really committed because there were a lot of hoops to jump through.”

But the purchase of the King Country farm gave the operation more scale, flexibility and certainty. Stock can be transferred from one farm to another, depending on grass growth, and the combined operation can carry more stock through to finishing, achieving a higher margin.

Rob says the Coromandel farm is the operation’s main breeding block. The King Country farm also carries breeding stock but its chief focus is finishing and grazing support.

Rob and Amelia work closely with a stock manager, who handles day to day work on the King Country Farm.

The Coromandel farm runs about 150 Angus cows and heifers and 1200 Romney ewes. Hoggets are mated in the King Country and return to the Coromandel as two-tooths. Steers and non-replacement heifers are also transferred to the King Country block.

When Rob and Amelia first started on the Coromandel farm it was carrying about 900 Coopworth ewes and 200 South Devon cows.

Rob says a significant investment was made in capital fertiliser, “which was flown on before we even got here”.

The cows and a large portion of the ewes were sold almost immediately, Romney mixed-age ewes were bought-in, and the remaining ewes were mated to terminal sires.

Amelia says the farm’s original cows were lovely but she and Rob felt Angus cattle and Romney sheep would be better suited to the operation.

“We bought two lines of Angus cattle initially and bred the sheep back to a straight Romney. Ever since then our focus has been on lifting the performance of the stock through better breeding.”

Rob is a big fan of the keep-it-simple, low-cost approach to farm management.

In his view, farming lost its way somewhat when farmers were encouraged to intensify too heavily.

“Some people will call me old-fashioned, but I like the traditional ways of keeping management simple and not overstocking. If you look after your animals, they will look after you.”

Blue sea, black cattle

Rob is particularly proud of the cattle on the coastal farm.

He says second-cut heifers are now keenly sought after, which shows how much the herd has improved over the last ten years.

Strong heifer performance is a feature of the property.

Heifers are mated at a target of 300kg in mid-October, calving as R2s in July-August.

“In recent years, 96-98% of our heifers have got in-calf within two cycles,” says Rob.

He puts this down to good feeding and good genetics.

“We feed them well so they hit the ground running.”

Heifers are calved behind a wire and supplemented with balage.

Amelia says they feed out by hand, a sometimes tricky job given the contour. But this helps the heifers get used to human contact.

“Temperament is a real focus for us,” says Rob.

“Our cattle have to be quiet and safe for us to handle. It’s also important because we have a lot of visitors to this farm and some of them have never been near livestock before.”

For the last nine years the herd has been mated to sires from Storth Oaks Angus Stud, Otorohanga.

Rob says Storth Oaks genetics have made a significant contribution to the performance of the herd.

When buying sires he pays close attention to Estimated Breeding Values (EBVs) and looks for bulls that rank highly for calving ease, birth weight, temperament and growth.

Heifers are mated for two cycles (six weeks). R3 and mixed-age cows are mated for three cycles but only those that get in calf during the first two cycles stay on the Coromandel. In-calf cows that were conceived during the third cycle go to the King Country, which has a later calving date, and are mated to Charolais bulls in subsequent matings.

“Those cows effectively become the replacements for the King Country farm. One of the luxuries of having the second farm is that we can carry more home-bred steers and heifers and we don’t have to chase the weaner fairs.”

Rob says the Angus-Charolais calves are very marketable and can be sold early if the weather gets dry.

Cows have to be top performers to stay on the Coromandel farm.

“This property is our stud for the whole operation. If they don’t produce a good calf in good condition, they are down the road.”

Amelia says Rob is strict about which cows and heifers he retains. Any cow that shows poor temperament or “even looks at him funny” is culled.

The best 50 heifers are retained and the rest are sold. About 26 vetted-in-calf heifers were sold this season.

Rob says the sale of these second-cut heifers helps to offset a drop in trading numbers on the King Country farm if the season dries up.

He says the strict selection process and the focus on top genetics is starting to pay off.

“Our own steers and heifers outperform any trading stock we bring in. It’s been six years since we had to calve a heifer here, and we are consistently seeing 96-98% of our cows rearing a calf.”

Beating the heat

Dry summers are the norm rather than the exception on the coastal farm, so stock numbers are almost halved by December 1 to ensure breeding cows and ewes get top priority.

Any surplus stock are sold or transferred to the King Country.

Amelia says the Coromandel farm carries about 4200-4500 stock units at the peak but this drops to about 2600su in December.

She and Rob have learnt a lot about utilising kikuyu pastures over the last ten years.

“You can get pretty good performance out of kikuyu if you fertilise it, manage it carefully and keep it alive. Ryegrass really struggles in the dry, but as long as you don’t overgraze kikuyu, it will respond quickly to a bit of rain.”

Rob says the farm was rotationally grazed for the first two years, but this didn’t suit the pastures or the soils.

“It just wasn’t working for this class of land, and stock were under too much pressure.”

So they switched to a set stocking regime.

Apart from the 6-8week mating period the cows are spread around the farm with the ewes.

“In the steeper country we are stocking the cows at about half a cow/ha,” says Rob.

The herd has responded well to this change. Cows are quieter and more content because there is less grazing pressure and a lower parasite burden.

“Set stocking helps us to build stock condition. It also helps us to protect the soils because we don’t get the erosion or pugging damage we got under rotational grazing.”

After calving, heifers are split into two mobs of 20-25. Rob says the smaller mob size helps heifers to settle down and hold condition.

During mating the mixed-age cows are run in three separate herds and rotated around the better contoured paddocks with reliable water. Bulls will often hang out in the shade and wait for the cows to approach a trough before doing their job.

Rob and Amelia buy one to two bulls a year and keep them for up to four years.

“This class of country can be hard on bulls, so we need to keep them young.”

Rob says breeding bulls are so quiet they can be scratched and fed by hand.

“Some people say that Angus bulls are wild, but we’ve never had a problem here.”

The breeding herd is also relatively young, with few cows over five years of age.

Rob says this is a deliberate strategy to keep performance up. Older cows are sold or transferred to the King Country farm.

“We only want to keep the very best replacements here, so we look closely at them every time they are in the yards.”

Heifers are calved in July-August and the older cows a month later.

“The key is to get calves on the ground as early as possible, then we can get them weaned and off the property before it starts to dry up. We have to make sure our breeding stock can perform the following season, so we are always planning one year ahead.”

Heifer calves are weaned at a target weight of 200kg and the steers at 240kg minimum. Angus steers are finished on the King Country farm at a minimum of 300kg carcase weight (CW) at 24-30months, and the Angus and Angus-Charolais heifers are typically finished at 240-260kg CW.

No Angus heifers have been finished over the last two years because they have been sold for breeding.

Rob says mixed-age cows on the Coromandel farm average about 550kg liveweight (LW).

“We don’t want a big, lanky cow on this country because they knock the hills. And we don’t want a little brick either. So something around 550kg is an efficient pasture converter and a good match for the contour.”

Last season about 60 Angus cows were mated to Charolais bulls on the King Country farm. Their progeny were finished in a cell grazing system along with steers transferred from Coromandel as weaners. Rob says forward steers are shifted every 2-4 days in the finishing unit. Weaner steers spend their first winter on the flats. During summer they are set-stocked among the sheep in the steeper hill country, returning to the cell grazing system at an average of 400kg.

“They are coming off Class 6 hill-country, so they wouldn’t reach those weights if we didn’t have the genetics.”

In summer, pastures on the steeper contour on the King Country farm are managed to build up a seed bank and provide quality feed for the following autumn.

Amelia says cows are a key pasture management tool on the farm. They are used to clean up rank pastures and improve pasture quality for lambs and other finishing stock.

Careful culling lifts sheep performance

The ewe flock on the Coromandel farm is subjected to the same rigorous culling regime as the cows.

“We are looking to find the best of the best from a relatively small gene pool,” says Rob.

He and Amelia run a two-flock system. Older and poorer performing ewes are transferred to a terminal mob and mated to Poll Dorset-Texel and Suffolk-Texel rams for early lamb finishing.

No hoggets are mated on the Coromandel farm. Instead, ewe replacements go down to the King Country farm. About 60% will be mated, returning as two-tooths.

Ewes on the Coromandel farm lamb at 135-145%, averaging 140% (survival to docking).

They are mated at 60-65kg and lamb from late July. Amelia says the early lambing means lambs can be weaned and shifted to the King Country when grass growth is at its peak.

Non-replacement lambs are finished at a target of 17kg CW-plus.

“We can send a unit load away from here in November and use the same truck to take prime cattle direct from the King Country farm to the processing plant,” says Rob.

Like the cows, ewes are set stocked around the farm for the bulk of the year.

Rob believes animal health is better as a result.

He and Amelia are reducing the use of chemicals, looking for safer and more environmentally-friendly alternatives. For example, Green Thistle Beetles are used to control Californian thistles on hard to reach areas of the King Country farm.

And they no longer dip for fly in the Coromandel. To reduce the risk of flystrike they use home-made fly traps built from 200litre drums. About 15 drums are spread around the farm, situated in low-lying gullies where flies tend to congregate out of the wind. Baited with a fish-gut slurry, these traps catch millions of flies in the peak of summer.

Rob says the incidence of flystrike on the farm is now very rare.

Ewes are shorn six-monthly, clipping about 2.5kg/ewe/shearing.

“We are growing more wool because the ewes are fed well.”

Despite miserably low prices, Rob and Amelia still have faith that wool will make a comeback.

“It’s just such an amazing natural product.”

They also see a strong future for quality grass-fed red meat that is produced in a sustainable and ethical manner.

“We get a range of visitors coming here from around the world and some of them arrive with a fairly negative view of farming,” says Rob.

“But when we show them how we produce grass-fed lamb and beef and how we take care of the animals and the environment, they go back to the Northern Hemisphere with a great story to tell about how it was raised and how good it tastes.”