Evaluation of a whole system

Trade lambs are a key farming enterprise at Hafton Station, but when they discovered drench resistance on their Hawke’s Bay farm in 2019, Michael and Karen Toulmin knew they needed to re-evaluate their

whole farm system. Words Rebecca Greaves and Photos John Cowpland.

The introduction of breeding ewes at Hafton Station, west of Hastings, is proving a successful tool in helping to manage worms.

The introduction of breeding ewes at Hafton Station, west of Hastings, is proving a successful tool in helping to manage worms.

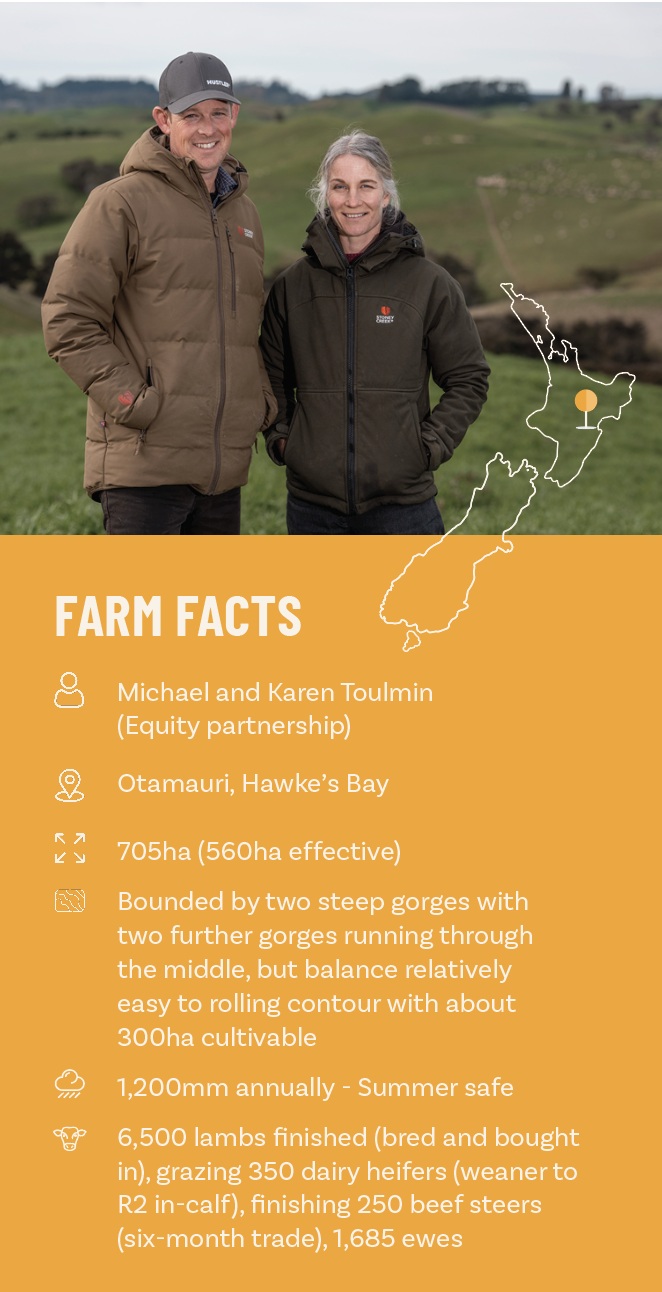

Michael and Karen Toulmin only took over at Hafton Station in May 2025, but they’re looking to replicate the successful formula they applied on their previous farm, Makuranui, which bagged them the title of Hawke’s Bay Farmer of the Year for 2024.

The dedicated couple has worked hard to get into farm ownership, and the move to Hafton represents an exciting, if somewhat daunting, step up the ladder. But it’s a challenge they’re ready for.

Michael grew up on a farm in Hawke’s Bay, while Karen is originally from Australia. She works full-time as a contaminated land consultant for HAIL Environmental. They have two children, Victoria, 14, and Connor, 12.

Their system revolves around four stock classes: trade lambs, breeding ewes, dairy grazers and beef steers. “We’re still finding our feet but we have taken the system from our previous property and are planning to replicate it here,” Michael explains.

Attention to detail is a feature of their business, and everything is run through FARMAX to see the profitability of the different stock classes. They also work closely with their AgFirst farm consultant, and are constantly reviewing their operation.

Trade lambs are the engine room and they expect to finish 6,500 this year (a combination of homebred and brought-in lambs). The plan is 2,000 lambs through summer, but the majority are finished through winter. Hafton has a history of cropping and improved pastures with 25ha currently in new grass. They plan to do 60ha of summer crop, which translates to 60ha of new grass next year, to accelerate lamb finishing ability.

They prefer to buy lambs from the same large stations in Taihape every year, finding they move down and perform well, although they do have to buy some through the saleyards.

Dairy heifers, about 350 annually, usually come in December as weaned calves and stay about 18 months, heading home in-calf on 1 May ready for spring calving. The heifers provide good cashflow, are easy to handle, enjoyable to work with, and fairly light on the ground.

They expect to trade about 250 beef cattle through summer, with R2 steers coming in at about 400–450kg in August and killed from January through to March, so they don’t take heavier cattle through winter. Although this six-month trade is generally the lowest-returning enterprise on the farm, the steers serve the purpose of controlling the feed surplus running up to Christmas once the trade lambs are gone.

Breeding ewes are a new addition, added to the system three years ago when the couple discovered drench resistance on their previous farm. They purchased 1,300 Kelso ewes already at Hafton, and brought with them 385 Romney ewes. They’re looking to see which performs best and will likely wind ewe numbers back to 1,000–1,200 next year. Ewes scanned between 175–200% this year.

Tackling drench resistance

When they discovered drench resistance on their previous property, they took a step back and evaluated their whole system. Recognising changes needed to be made, they decided to add the ewes in, giving them an undrenched class of stock.

They purchased ewe lambs from Te Whangai Romney stud, and continue to do so annually, as they don’t breed their own replacements. The Te Whangai sheep were purchased specifically for their worm resilience.

“Trade lambs are still a big component of what we do and we’re not a closed system, so there is the potential for new worms to be introduced, though ideally, they’ll be killed with a quarantine drench,” Michael says. “We are basically trying to dilute the population of resistant worms we had.”

While there’s a cost attached to buying the ewe lambs each year, initial indications are that they’re doing the job, and the cost of not acting was simply too great.

Karen adds that it’s a whole system approach, which is driven by the worm problem.

Other tactics to combat drench resistance include having a high cattle ratio, minimising drenching (for both sheep and cattle), managing stock rotations, and putting in more crop for young stock over the summer.

They went from drenching everything to being very selective about what gets a drench. Ewes received a single drench this season, before the ram went out. Beef steers get a quarantine drench when they come in and once the dairy heifers reach 350kg they generally won’t require drenching either.

Drench resistance in young calves is also a potential risk. Individual weight gain is tracked for every animal and they are very careful about drenching only those animals that need it.

Pathway to Hafton

The couple purchased their first farm, Makurarui in 2010 in partnership with Michael’s parents, and were able to buy them out of the 211ha farm in 2014.

It was hard grind. Michael worked off farm for Kiwi Lumber from 2009 to 2021 while Karen did the necessary stock work during the working week. On the weekends all the major stock work was completed together. They reversed roles in 2021, with Karen returning to work and Michael focusing on the farm. With the help of family, many hours and weekends were spent moulding the farm into the slick operation that bagged them the Farmer of the Year title.

“It’s a bit scary how it’s all come together. We thought it was a pretty far-fetched plan when we wrote it down.” – Michael Toulmin, Hawke’s Bay

Teamwork and goal setting is a feature of their business and the couple are testament to the power of dreaming big, making a plan and executing it.

They attended an Agri Women’s Development Trust course at the start of their farming careers and set a farm business plan early on, believing they were setting some lofty goals. The aim was to get to 400ha, feeling that would give them enough scale.

When Hafton came up for sale they initially thought it was out of reach, on their own at least. They felt the timing was good in terms of better commodity prices and some relief on interest rates. They made a few phone calls and were able to come up with two minority shareholders fast, which likely says something about how highly regarded they are as operators.

The company owns everything in equity partnership and Michael has full autonomy over the day-to-day running of the farm. They set a formal budget with Farm Focus and hold a board meeting every three months. “We’re very happy with the shareholders we managed to find, it was a pretty quick turnaround,” Michael says.

“It’s a bit scary how it’s all come together. We thought it was a pretty far-fetched plan when we wrote it down. We thought there was probably a stepping stone between Makurarui and here. This place ticks all the boxes, it feels like we’ve gone straight to the end game. It should keep us busy for a while.”

Farmer of the Year

Interestingly, it was entering Farmer of the Year in 2020, and not winning, that proved a pivotal moment in their farming careers.

“We were not successful, however the feedback we received from the judges really made us think about what we needed to do to get our business to the next level,” says Michael.

While their financials were solid and the business profitable, the couple found they were lacking in other areas. This caused them to reflect and make significant changes to the business, at around the same time as they discovered the drench resistance problem.

One of the major changes was the trusted team they had around them and bringing more people into the equation. They changed accountants and brought in a farm consultant.

“We built a really strong team. The vets have also played a big part. It brought in a bit more strategic guidance.”

Living the dream

For the Toulmins, farming is a business but it’s also a way of life. Hafton also offers a change in lifestyle, with plenty of character in terms of the scenery and bush. Michael and Connor can now walk out the front door and go for a deer hunt.

“We had quite strict criteria. We wanted rainfall and 50% tractor country. We also didn’t want to leave this district. It’s a great area and all our friends are here.”

For Michael, the ultimate end goal would be if one of the children wanted to become involved in the farm business. “Initially, it was about building enough scale to afford to put the kids through school.”

Karen adds that being able to put a worker on one day would be nice, and spending more time out in the boat, which is currently seeing more time in the shed than on the water. For now, off-farm income is a critical part of the equation.

“I’d like to get to the point where we have more time to do things together as a family,” she says. “My career is just taking off again with HAIL and I would like to see that go forward.”

For the foreseeable future, the focus is on knuckling down and increasing production at Hafton. Cropping and new grass are seen as the key to driving their profitability. “We are measuring production very closely. People may see it as a cost but we believe it pays off.”

Other key areas for investment include fertiliser, animal health (a non-negotiable) and development of the land through fencing and work on the water system.