Development spurs system change

A switch to tall fescue and irrigation has transformed the finishing operation on Tom and Sam Macfarlane’s Melior Venison farm in South Canterbury. By Lynda Gray. Photos by Anna Munro.

A switch to tall fescue and irrigation has transformed the finishing operation on Tom and Sam Macfarlane’s Melior Venison farm in South Canterbury. By Lynda Gray. Photos by Anna Munro.

A change from ryegrass to tall fescue-dominant pastures has created a better feeding platform for young stock at Melior Venison.

“I haven’t sown a perennial ryegrass for six years because I think we have better options for our system and land type,” Tom says.

What’s been developed is a pasture mix with Hummer, a tall fescue variety, as the base. The exact mix grown, and the establishment process followed is dependent on soil type, specific environmental considerations and the seasonal feed demand of the young stock grazing it.

The change to fescue as well as the development of irrigated flats for winter crop and high-quality prairie grass and red clover has transformed the farm from a predominantly breeding to a mostly finishing system. The Macfarlanes’ beef operation appeared in Country-Wide June.

When Tom and Sam moved to the farm, formerly known as The Kowhais, in 2013, replacement of the perennial ryegrasses on the lower lying country, and browntop on the steeper country was high on the To-Do list.

The high-endophyte ryegrass was never going to work in the finishing system they wanted to build. Tom was aware of tall fescue’s attributes. His father Andy was a co-founder of pasture and forage company Agricom and an advocate of the perennial grass. However, Tom did his own background research before deciding it was the best fit.

“It was always our intention to change to a more profitable pasture. We started with fescue and kept evolving it from there.”

Drawing on Agricom advice, the Macfarlanes chose Hummer with novel endophyte (MaxP).

On the higher fertility mid-altitude country, a Hummer (14kg), Relish red and Tribute white clover (3kg each), Atom prairie (4kg) and Agritonic plantain (1kg) mix is grown. The sowing rates are relatively low and indicative of a well-prepared seedbed. Attention to seedbed preparation never used to be a huge priority, Tom admits, but through trial and error it became obvious that a two-year annual ryegrass to brassica crop rotation was the best way to eliminate weeds and weed grasses, build fertility, and therefore improve the chances of successful fescue establishment.

An Asset ryegrass and Hunter brassica mix has worked particularly well.

“It’s a good fit. It breaks down the thatch left from old pastures and also produces feed at key times when we need it for the young deer.”

The spring-sown mix which persists until drilling of a permanent grass the following spring means fewer tractor hours are spent on establishing summer crops.

“If we grew rape for a summer crop, we’d need to follow on with an autumn-sown short-term grass and that can be a problem on our country because it can either be too wet or too dry making establishment hit-and-miss.”

This season Oakdon, a new and first New Zealand-bred meadow fescue was added to the spring-sown Hummer mix. It’s more palatable than tall fescue and has strong mid spring to late summer growth. It’s slower to establish, giving the red clover a chance to get a good foothold while soaking up any excess nitrogen that weed grasses could tap into.

On the steeper, drier and variable fertility north-facing hills the fescue mix has been altered with Savvy cocksfoot added. Cocksfoot will persist during the dry summers, bounce back quickly after rain, and provide good standing hay for strip grazing in the winter. It should last seven to 10 years making it a true permanent pasture.

The hard graft of fescue development is complete, and the Macfarlanes are targeting crop and pastures in particular areas.

A good example is a steep hill marginal block in the south corner of the farm immediately below a forestry block. Vehicle access is difficult and there are environmentally sensitive areas.

“It’s not easy to break-fence so we’ll do a two to three-year rotation of annual ryegrasses and summer crops before permanent pasture.”

Has the pasture makeover stacked up; will it produce more kilograms of drymatter, meat and income per hectare?

In simple terms it’s elevated the farm from sheep and beef breeding generating 10-15c/kg DM to predominantly finishing, generating 30-plus c/kg DM consumed.

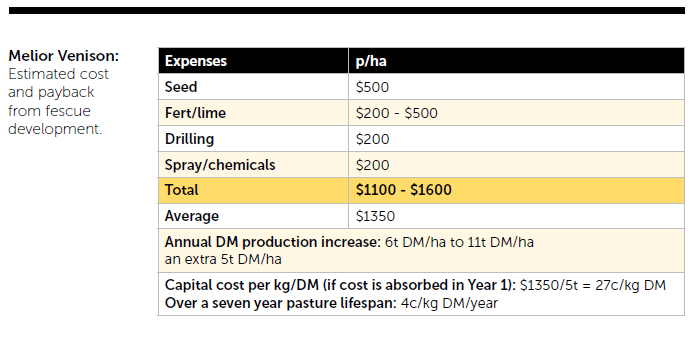

Tom estimates the development is growing an extra five tonnes DM/ha each year at a cost of about 4c/kg/DM assuming a seven-year pasture life.

“The costs are covered in the first year assuming the livestock finished generate 27c/kg DM or more, and beyond that the extra production is free.”

New chapter

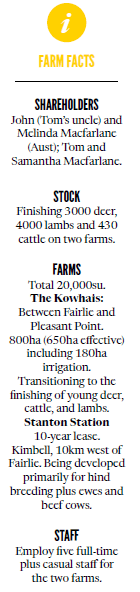

A 10-year lease of Stanton Station, a 20-minute drive from Melior Venison, (Country-Wide June) is a new farming chapter.

The lease arrangement unfolded from 2020, when the venison schedule dipped out at $6/kg which hit income hard. The Macfarlanes had to reassess and reset what they were doing.

“We had highly productive country and highly productive stock. The hinds were productive but not profitable on that country. We wanted to maintain the balance of what we’d developed and also ensure the supply of quality stock.”

They were keen to grow scale and scope but restrained by capital and unable to buy more land. Instead, they expanded without capital outlay by negotiating the lease of Stanton Station which they identified as ideal breeding country for hinds as well as cows and ewes.

“It adds balance to the overall operation. We were lucky to find investors who had a shared vision to turn it into a deer farm.”

Downland pastures will be upgraded but probably not with fescue given the limited 130ha of easy contour country and the need for a faster rotation to fill feed supply and quality gaps.

Regardless Tom says they’re committed to the deer industry.

“We’re focused on what we’re doing with deer. For us it’s about constant improvement and a belief and fascination with how we can do that with genetics and feeding.”

Farming pathways

The development of The Kowhais/Melior Venison is the first full-on chapter in Tom and Sam’s deer-focused farming career. Both 34, they started out in 2013 managing The Kowhais for Tom’s Australian-based uncle and aunt.

In 2017 they formed a 50:50 equity partnership, buying the former Deer Improvement stud breeding farm at Balfour in Southland and renaming it Melior Genetics. Last year, the farming business was restructured with Tom and Sam leasing both South Canterbury farms from a group of owner investors. The Macfarlanes have a 25% stake in the collective farming business, called Melior Venison, which they hope to increase to at least 50%.

They employ nine onfarm staff, most under the age of 35. Charlie Johns manages the South Canterbury farms, and Sam Bishop Melior Genetics.

Sam Macfarlane supports them with practical advice on staff recruitment, giving feedback on the wording for online job advertisements to emphasise the values and essence of the farming business. She also mentors managers on how to approach performance reviews and encourage the input of employees.

“We want the people who work with us to be motivated and it’s not just about money, it’s also about creating the right working and social environment. I enjoy bridging the gaps in management and communication skills that aren’t taught at university.

Spending to save

Tom takes a slightly different view on how to cut farm expenses.

“I think as farmers we tend to look at costs and farm working expenses in isolation rather than the long-term potential gains and return on capital from spending.”

A good example is the $1000-$1500 annual spend on soil testing to identify areas that require more or less fertiliser, or specific nutrients. It costs about the same as a tonne of fertiliser, but Tom regards it as smart spending because it leads to more targeted fertiliser inputs which over time will potentially reduce the amount used while increasing the productive potential of the land.

Heartbreak and change

Amid the buzz, excitement and achievements of farm developments over the last few years has been personal loss and grief for Tom and Sam. The year before the birth of Jack (almost 4) was the stillbirth of Penelope in 2017 at 32 weeks. In 2019 Genevieve was stillborn at 26 weeks.

The deeply traumatic time was tempered in part by the empathy, phone calls and cards from other couples and families affected by stillbirths, Sam says.

“It’s mind-blowing the number of people who have experienced similar to what we have.

“The more we make this a normal conversation the less alone everyone who goes through it will feel.”

The couple coped with the losses of their daughters in different ways. Tom immersed himself in the farm development while Sam’s life ground to halt as she questioned and reassessed her life to date, and how she wanted it to look in the future. This included resetting her role in the farming business. Until then she had fulfilled a number of roles typical of many farming women.

“I like organising systems and I picked up the tasks that others didn’t want.”

Financial administration, taking care of online media for the marketing and promotion of Melior Genetics as well as for recruitment of employees were all on her unwritten job description. But despite the work, effort and results Sam felt unfulfilled, undervalued, and unsupported in the business.

On making the decision to step back from those roles, Sam, a qualified hairdresser, opened in December 2020 Boss Salons in Fairlie. A nanny takes care of Jack and household duties, and Sam works four days a week, including Saturdays when Tom has a farm day with Jack.

“For us it’s meant working and thinking differently. My work life is now a lot more balanced than it used to be.”

The Macfarlanes are looking forward to the birth of their baby in late July.

Sam is still involved in the farm business but in more of a strategic thinking and advisory capacity. A good example was the move to take on the Stanton lease.

“I could see the opportunity and value it could add from the get-go, and I pushed Tom to follow through.”

Next gen challenge

Some people are born farmers and that’s cool, but the industry needs to do a better job of selling it as a career to the next generation. That’s the Macfarlanes’ view based on talking with a number of Lincoln University students over the last few years.

Undergraduates often aspire to rural professional roles because they aren’t aware of the opportunities to learn and grow a broad skill set, as well as the earning potential.

In the Federated Farmers 2021-2022 remuneration report, 13% of farm managers were under the age of 30; the median TPV was $80,500 and the maximum $149,000.

Tom says the low percentage under the age of 30 is a concern.

“I think for industry progression we need more in that younger age bracket. It’s a massive challenge.”

Farm owners need to do their bit in matching their expectations for high calibre managers with the employment package, especially housing, he says.

“If you want your manager to go above and beyond and have that ownership mentality you need to supply the right environment, facilities, and a house an owner would be happy to live in.

“I often hear ‘it’s adequate for staff or a manager’ but that isn’t fair. Adequate is not good enough.”