Keep the finisher in mind

Dairy farmers wishing to phase out bobby calves will need to raise animals that will compete with other land uses. Sheryl Haitana reports.

Farmers may need to collaborate effectively in order to drive more value from each calf born on dairy farms, Focus Genetics’ Rebecca Hickson says.

Rebecca, the scientist running Pamu’s beef breeding programme, says the dairy industry is in a position where if they want to phase out bobby calves, they need to produce a calf that is more attractive to the beef market.

That involves thinking beyond just an easy birthing calf who is born on time, to thinking about the person who has to make money from finishing those animals.

As part of Pamu’s dairy-beef breeding programme, Focus Genetics is going to start measuring more traits from artificially reared dairy beef calves which require different characteristics to beef calves reared on their mothers. Traits that are important for dairy terminal sires in an artificial rearing system are quite different to stud herds producing the bulls in a cow-calf system.

“We are looking at how we can essentially collect data from next year on our dairy beef calves, so we can understand the artificial rearing performance.

“We need calves that will compete with other land uses if we want to make more space for finishing dairy-origin calves.”

Something that came out of the B+LNZ Genetics Dairy Beef Progeny Test (DPBT) is that the beef calf 200-day weight estimated breeding value (EBV) didn’t predict the 200-day weight in an artificially reared calf, Rebecca says.

“It makes sense when you think about it, the 200kg weight EBV is when you wean a six month old calf off its mum.

“When you put that same calf into a dairy beef system, one of the first things is we wean to a fixed weight at a young age.”

Those weaned calves are then going into poor-quality pasture over summer while not drinking off their mum.

“We are asking them to perform in a different environment.”

Another result of note from the DBPT was a two week difference in age at weaning from different bulls.

“If we could have more progeny from the bulls whose calves are weaned two weeks earlier that would be great because time on milk is the most expensive part of artificial rearing. “That’s a trait we are not picking up in our traditional beef system.”

Another factor they want to try and measure from bulls is the drinking ability of different calves, Rebecca says.

“The ideal is a calf is born easily, it then jumps up, hops on a feeder and grows well.”

Sometimes people talk about ‘stupid calves’ and it is a significant cost in labour if it takes twice as long to teach all those calves to feed.

“It’s easy to quantify that that actually matters, it’s much harder to measure it. There is a human element to it. We are still thinking about how we do that.”

The other big piece of the puzzle is growth rate. When farmers are considering returns through marbling, and the other various premiums, at current prices, it still comes down to more weight on the hook.

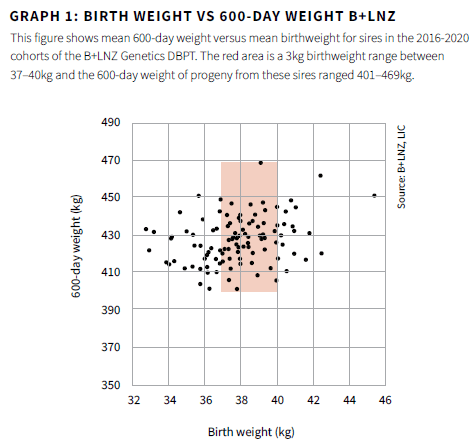

In the DBPT calves born within a 2-3kg birth weight bracket, had a 60kg difference by the time they reached 600 days.

All of those calves born were perfectly acceptable for the dairy farmer and all within the bracket for a calf rearer to happily to take them, but there was a 60kg variation for the farmer finishing them.

“All of those calves the dairy farmer would have been happy with, but the impact on the finisher was really significant.”

MATING TO SUIT THE FINISHER

The rearing cost of dairy beef animals and the impact of growth rate on the farmers finishing these dairy beef animals is a big part of creating more demand for these calves. If dairy farmers want to see an expanding dairy-beef finishing sector, they need to factor these things in when doing their mating plans and choosing bulls, Rebecca says.

The biggest cost issue is the later-born calves who need to be carried over a second winter.

There is a big bunch of dairy beef calves born in week seven, eight and nine of mating that could be finished before the second winter, Rebecca says.

“If we could put some really high power growth bulls in via semen at that stage that’s going to up the odds of getting them off before the second winter.”

Pamu is looking into using automatic heat technology on their dairy farms so they can do more artificial insemination (AI) for beef semen.

“We are thinking about how we can structure our mating plans to get more early born beef calves and get the right calves at the right time.

“I think semen will get us a long way there in making better calves for finishing.”

Sexed beef semen will also become a more popular option as the conception rate improves, she believes.

There is also scope to consider specialised systems to rear those later-born calves through their first summer, Rebecca says.

If those calves are fed better during that first summer it increases their chances of being finished before a second winter.

“You have to do your sums on what that feed in that first summer will cost you – but to me it’s a no brainer. On feed efficiency, methane, cost – it makes so much sense to put that feed in that first summer. In exchange, you don’t have to feed them in their second winter.

“It’s not going to work for every calf, but there are some who you can turn from a two-winter to a one-winter animal with a bit more high-quality feed in their first summer.”

A good dairy beef operation can achieve 1kg/day average gain over a 12-month period, which means calves have to reach 235-240kg before their first winter, if they’re to have a realistic chance of getting them off before their second winter, Rebecca says. This is one of the reasons finishers prefer cow-reared beef weaners.

Finishing farms have years of experience taking big robust 230+kg beef calves in autumn, and systems are set up to do this. It’s a big change to be taking on 100kg calves in December, which are not big or robust.

Those calves going on to finishing blocks are also competing for summer feed with fattening lambs.

“At Pamu we are looking at a stage 2 rearing farm. If we can take them through that first summer on a different platform, where they are the priority animal fed high-quality feed, it requires less change for those finishing farms, they then still get those robust animals in autumn.”

MAKING MORE FROM THE FOUR-DAY CALF MARKET

One challenge going forward is every farm will have a similar formula and thus as more dairy beef calves flood the market, how do farmers gain the best value.

“The four-day-old dairy beef calves are not a high-priced product, and are never going to be because of the supply-demand situation we have in New Zealand. If we can come up with ways of getting a beef calf where we previously had a pretty unrearable calf, at a similar cost, that’s good.”

One of the sticking points to gaining better value at the four-day-old calf markets is the huge number of dairy beef calves born from unregistered bulls. Currently rearers or finishers are left with selecting calves on what they look like in the pen, without any data on the potential growth rate.

“When you go to a four-day calf market, there is a huge variation on what is paid for. Most of that comes down to the buyer’s expectation of growth. It’s pretty crude based on what colour they are and how big they are. Those buyers don’t have the bull sire information so they’re guessing.”

That makes it hard to build trust and if a rearer buys a line of dairy beef calves that don’t grow, it puts them off buying again.

Farmers wanting low birthweight bulls don’t spend more on a low birthweight/high growth bull, because the buyers will look at the smaller calves in the pen and pay accordingly without having that bull information to take into account.

“We need to join all those dots, so if you use a moderate birthweight/high growth rate bull you’re going to make more (from the calves) than if you buy a moderate birthweight/low growth rate bull.”

The dairy beef indexes that exist are all heavily weighted so that the calf has to be born all right, so they mask the differences in how the calf is going to perform.

“I think there should be a separate index for trading the four-day-old calf, measuring what the rearing potential is of that calf.”

As farmers use more beef semen from registered bulls, that bull information will become more easily available to buyers. Having contracts with finishers directly is also a way to factor in a better return on investment on better bulls, Rebecca says.

Because of Pamu’s closed system they have the ‘buyer’ lined up and in the past it didn’t matter so much if the calves were licorice allsorts, he says.

But that formula is changing. At the Renown Farm where they do the Dairy Beef Progeny Testing, the mating plan is sexed semen for replacements and beef semen for all non-replacement matings. The non-replacement calves now stand as better dairy beef options to rear. “I went around some of our dairy farms poking my nose into the calf pens. At some farms they had the heifer replacement calves, then pens of dairy crossbred bull calves and a smattering of beef calves.

“At Renown, they had the dairy replacement calves, then in the other pens they were all really good beef calves – I wanted to rear every single one. This is a system where every calf is here for a reason beyond wanting the mum to make milk.”

No one breed is the right breed to use for dairy beef, it always comes down to using the best bulls or the best team of bulls, Rebecca says.

“With any breed, I could find you a good bull, I could also find you a terrible bull.

“Jumping on a breed bandwagon is a recipe for inappropriate bulls of that breed being used.

“When we plot for the DBPT by breed, and if we draw a circle around the good values, we find bulls from lots of different breeds in that circle.”

Focus Genetics is producing a dairy terminal sire, a Stabiliser, which is a composite. “Essentially we are trying to bring in good bulls, not being confined to a breed.

“The Stabiliser has been a good performer overall, and we are finding top performers within that for AI. It’s doing what we expect in our Pamu herds in terms of calving ease, and growth and carcase performance. If we can get some of those artificial rearing traits into our programme we will make this even better.”