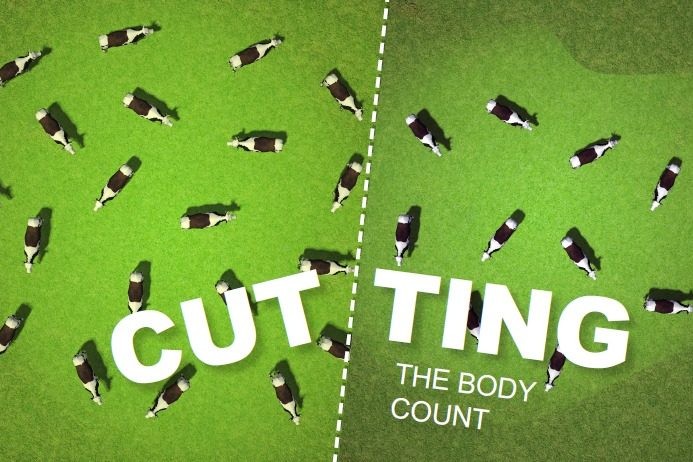

Cutting the body count

Dutch farmers are being coaxed into significantly reducing stock numbers to combat nitrogen pollution. Kiwi farmers face similar moves for climate change reasons. By Phil Edmonds.

Dutch farmers are being coaxed into significantly reducing stock numbers to combat nitrogen pollution. Kiwi farmers face similar moves for climate change reasons. By Phil Edmonds.

Not very long ago a farm stocking rate was little more than a concept in a textbook. But in next to no time a stocking rate has become a proxy for how adaptive and forward-thinking farmers are on the environment, and most recently it’s been used in Europe in an attempt to signify a straightening out of farming’s domestic and international reputation.

Should we be taking any notice?

Late last year the Dutch government unveiled a 13-year, €25 billion (NZ$42.8b) plan to significantly reduce the number of livestock in the Netherlands in an effort to address its excess nitrogen problems. The initiative will start as a voluntary programme with farmers compensated to leave farming. By the end of the term, livestock numbers in the Netherlands are anticipated to have fallen by a third.

As would be expected, there was some opposition to the plan in the Dutch farming community, but the new directive had been years in the making, and eventually gained a coalition of support within the government.

Nullifying arguments that it would permanently damage food production which the Dutch led the world in, a government

party spokesperson for agriculture said the Netherlands had been good at feeding the world, but it hadn’t worked for the country so change was necessary, and that change would be something other countries will be able to learn from. Several voices, including Greenpeace New Zealand, insisted there is already plenty to learn from it and called for an identical approach to be adopted here. But opponents to such a destocking measure have pointed out, at a basic level, you can’t compare the Dutch and NZ farming systems.

As it is, the Dutch stocking rate (which includes pigs and chickens) is four units per hectare of agricultural land. This compares with DairyNZ’s measure of average cow per hectare of farmland as 2.84. Not like-for-like data, but enough to create a sense that NZ farming is less intensive, and therefore less in need of radical overhaul.

Nevertheless, the premise of destocking for the betterment of the environment remains a live issue, and one that will continue to generate attention in NZ, regardless of how different we position our farming systems to those in place in Europe.

Possibly partly influenced by the Dutch government’s move, Newshub Reid Research included a question in a February poll on the need for New Zealand to reduce livestock numbers to combat climate change. This reason is not quite the same as the motivation that has driven the Dutch move (nitrogen pollution), but the result found 50% of those surveyed did not believe this was necessary, compared with 38% who said yes. The balance of respondents was unsure.

Farmers will have taken some heart from this – that they have more support than not to continue farming to the extent they do. This perhaps reflects an acceptance that NZ does not farm ‘industrially’ as is insisted by those pushing to curtail the dairy sector’s footprint. And it may also reflect an acknowledgement that export revenue generated by our primary industries is critical to the NZ economy (especially recently).

At the same time though, the poll result does not represent an overwhelming ringing endorsement of the status quo and suggests there is a lot more to do to maintain the case that we’re on the right track.

The trajectory of NZ’s stocking rate has become a barometer of farming’s ability to adapt to environmental pressures. When the Climate Change Commission made its assessment of how agricultural emissions are projected to change over the next 10 years, it anticipated herd numbers would fall nearly 14% by 2030. So, stocking rates will be continually watched, and like it or not, be a marker of progress.

It is a blunt tool to use in judging the adaptation of our farming systems, and even Minister for Climate Change James Shaw has been reluctant to be specific on a necessary drop. In response to the Newshub poll, for example, he said it wasn’t his decision to determine how many cows there are, only to find solutions to reduce agricultural emissions. Yet of those solutions, the easiest one to understand and remediate the problem is by lowering stock numbers.

Even if farmers consider this to be a simplistic answer to cutting methane emissions, it was supported by the Agricultural GHG Research Centre report on options to reduce ag emissions in NZ, which showed that reducing stocking rates (in conjunction with) improving productivity per animal consistently reduces GHG emissions by up to 10%. This action was noted as more effective than other operational changes considered (for example switching to once-a-day milking or using low-protein supplementary feeds). It was also said to be more effective at reducing emissions intensity.

Unlike in the Netherlands however, the NZ government is very unlikely to mandate a reduction in herd sizes. For a start there are seemingly obvious reasons cited above as to why it would be difficult to justify. But at the same time the Government is not ignorant of the need to make sure NZ is still seen among the world leaders in environmental stewardship of the land that delivers the food overseas consumers pay a premium for.

Shortly after the Netherlands launched its plan to cut livestock numbers to help restore its environment, the European Union announced a €13.4 million (NZ$23m) campaign to run over the next three years to promote European dairy as the ‘sustainable choice’ and European beef and lamb as ‘working with nature’ in Asia and the United States. This will be the first time the EU has invested in a coordinated, sustained push of its dairy sector. Based on the stated focus, it’s inevitable that the marketing will draw on the kinds of proof of commitment to support the environment that has been shown in the Netherlands.

Is this a big deal?

Director of the Lincoln Agribusiness and Food Marketing programme Nic Lees says it is something NZ should take note of. If the EU is able to build awareness among consumers in markets (that NZ trades in), that shows it is measuring its agricultural environmental footprint, and is able to point to it falling, we will have to consider how we respond.

“To date, NZ has tended to rely on our reputation rather than validating claims.”

For a brief perspective, we’re clearly not going to be losing sleep over the prospect of a war of words in Asian supermarkets and foodservice companies on which country has the best stocking rate. No matter how engaged overseas consumers are with the provenance of their food, no consumer research done to date shows stocking rates as the factor that tips the balance in a purchasing decision. But there will still be a need to do something. Over the past couple of years, the Government has been investing energy in understanding how NZ’s farming system could be defined as regenerative in order to marry up with the ‘on trend’ interest in Regen Ag.

The Government’s blueprint for the future of our food and fibre sectors – Fit for a Better World references it in its vision (developing modern regenerative production systems). It conveys an expectation that regenerative farming systems will leave behind a smaller environmental footprint. You could say this implicitly means a lower stocking rate. Will this be enough to outfox a big budget EU campaign to elevate its dairy products?

Unlikely. There’s some scepticism that regenerative agriculture is not much more than this year(s) thing, and what is needed to be credible is more rigour in a message that points to verified measurements. To be fair, measuring performance is at the heart of what the Government is recommending, but while regenerative agriculture remains undefined, we can’t sit around waiting to see if we are officially regenerative or not.

Lees suggests rather than persevere with regenerative agriculture as a means to combat rivals in market (and avoid discussions about stocking rates) NZ has an opportunity to create its own, unique brand of ag, which could incorporate a range of provenance factors including our sustainable biodiversity.

Adjunct Professor at Lincoln University Jacqueline Rowarth says ‘grass fed’ still has traction that we should be making more of.

“It is more important to consumers than organic, which is used synonymously with regenerative agriculture by some proponents”.

Like Lees, Rowarth suggests NZ use a different but aligned term to explain what we do, acknowledging that the hype around regen is loud, and presumably makes sense to have some association.

For NZ farmers it’s tempting not to see any dots to join here – that herd size (and its ramifications on the local environment) has no place being documented on a product packet in a foreign supermarket. Instead, what still really matters is being able to produce what’s required more efficiently and cheaply than others. It would appear, however, that Dutch farmers have given up on that focus. We’ll need to watch and determine whether their move turns out to be salvation or death knell.