Constantly making it better

A focus on bull beef following years of drought has worked for a North Canterbury couple. Story and photos by Annabelle Latz.

A focus on bull beef following years of drought has worked for a North Canterbury couple. Story and photos by Annabelle Latz.

Drought recovery brought a change in direction for North Canterbury farmers Nic and Andy Fairbain.

Farmers in the region have strained memories of the drought-stricken years of 2014 to 2017, but the following recovery years opened up opportunities for the Fairbains from Scargill.

Andy, 60, and Nic, 54, live on the 300-hectare rolling hill farm Andy’s great grandfather bought in 1919, where they have always traditionally run sheep. They got into rearing bull calves as a way of restocking after the 2014-2017 drought.

Having dabbled at rearing calves over the years, they had the quick and efficient infrastructure.

“We soon realised we enjoyed farming cattle more than sheep,” Andy says.

They have the place humming, running one third bulls to two thirds sheep, the goal and focus to create a farming system which allows stock to receive optimal feed and water all year-round.

Andy is always thinking about feed and feed budgets.

“It’s rewarding to see results on margins and finances.”

Their 24 year-old son Fergus works in Christchurch as a builder.

Until last year Nic has always worked full time off farm. But, it was always a struggle to work both farm and full-time work.

“I used to turn myself inside and out getting it all done between my full-time job off the farm, calf rearing and lambing,” she says.

Now she works more on the farm so it’s a better balance.

Andy was a full time shearer for 12 years after completing a Bachelor of Agricultural Science at Lincoln University, and has enjoyed the move towards bull finishing.

“I had always wanted to be a farmer, the shearing funded me into the farm.”

Tweaks and changes

Finding the right balance for stock numbers has required some tweaks and changes. After the drought years they peaked at a 250-calf rearing system, which was a 50/50 ratio bulls to sheep. Last year dropping down to 120 calves meant less pressure on water and feed, describing February to October of 2021 as horrendous, where they were constantly tied to the farm feeding out.

The Fairbains have dabbled with bull breed combinations like straight Friesians, Friesians crossed with Angus, Hereford or Murray Grey. For their farming system the timing of the straight Friesian works best, buying in August, and going straight to once a day feeding using a mix of cows’ milk and powdered milk.

They learn from their calf suppliers, North Canterbury’s Rotherham dairy farmers Simon and Leanne McAdams. Nic and Andy say they can always talk to them about problems and questions because they’re the experts. It’s all about continually tweaking what they do to achieve the best outcome.

They worked out that calves need 1.5-2 bags of milk powder equivalent a calf.

“By collecting pods of colostrum and penicillin milk we can give them that extra quantity for a cheaper price,” Nic says.

“We absolutely thump the feed into them when they first arrive, we give them plenty.”

Adapting with North Canterbury’s seasons can be tricky. They buy barley, sell stock and fill the hay sheds when they can.

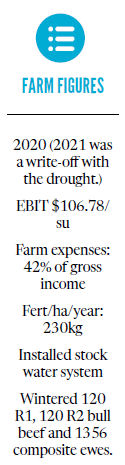

In the perfect world, Nic and Andy would finish all their bull calves, but the season is dependent. They winter 120 R1s and 120 R2s, having dropped the beef numbers from 230 reared each year to 120, due to water regulations. As of the end of June they were wintering 1356 ewes.

They sell half the R2s in June and the rest are carried through to spring, which requires some sort of summer crop either side of February. Last summer they planted eight hectares of kale, and maize is another option.

Maize has been okay but has limitations, it’s not high quality and they can’t make grazing maize into baleage.

“Kale can let you down in a drought, maize is good in drought,” Andy says.

Andy and Nic buy extra water units from their local council and no longer rely on animals drinking from creeks. Upgrading all the troughs and power supply have been significant expenses, but unavoidable and worth the investment.

Andy and Nic now pay for two more points of water from their local council which cost about $20,000 a year in total, as they can no longer rely on animals drinking from creeks. They have about 15 new cattle troughs which cost about $10,000.

“Upgrading all the troughs and power supply have been significant expenses, but unavoidable and worth the investment.”

When comparing a prime bull of about 600kg to a prime steer about 540kg, Andy says they are magnificent animals.

“The way they produce meat, they definitely have a higher growth rate.”

The Fairbains aim for 550-600kg for a finished bull, weather dependent. Last year the bulls were sold around the $1800 mark.

The temperament of bulls is well-managed.

The R1 bulls reaching puberty pose challenges running on winter feed when they are harassing each other and subsequently losing condition. The solution has been Bopriva, a two-dose vaccination to inhibit testosterone temporarily. The young bulls have their second injection timed just before they go on the fodder beet. They learned about Bopriva from their local vet Gerard Poff. The cost is $15 per animal, and has no effect on the meat.

“It means they use their energy to eat rather than chase each other around,” Nic says

They’ve tried other options to mitigate challenging behaviour, such as smaller mob sizes, mixing steers in with the bulls or mixing the ages. Bopriva proved the best option.

“Nic does the winter breaks on the fodder beet, and it’s much preferable when they’re behaving themselves.”

Ewes a good fit

Andy and Nic see the good fit that ewes are to their farm, that it’s good to have options and capitalise on a good market.

“With the way prices are at the moment for sheep, it makes the option pretty irresistible,” he says.

They would like to run one big mob of ewes on a long winter rotation.

Increasing sheep numbers has been an easy decision with the attractive schedule of $8 or $9. Buying in 1400 Composite ewes at the moment was easy, given the “unbelievable” season with continual grass growth throughout summer into winter. Feed’s been so good the last few months, they recently bought a unit load of lambs from Southland to keep the feed under control.

Buying in 1400 Composite ewes at the moment was easy, given the “unbelievable” season with continual grass growth throughout summer into winter, paying about $220 for the in-lamb ewes.

Feed’s been so good the last few months, they recently bought 710 lambs from Southland to keep the feed under control, paying $116.36 excl gst/head.

Nic says Andy is good at managing feed and water.

“So in a testing year we can keep options open, like buying in-lamb ewes which we don’t always do, but if the market is right, it’s ideal.”

Sheep performance is enhanced by farming bulls who retain the quality in the pasture by not grazing it down too hard, and controlling surplus growth.

Cattle dilute the number of parasites which could potentially be affecting the sheep.

“That is a big part of the reason of why you would want to be farming both, because the biggest enemy of a sheep is another sheep,” Andy says.

Buying younger sheep if they’re at a good price, if there is a good feed surplus, is another part of their sheep farming model.

“It’s about getting a good price when you can and jumping on board.”

They lamb at an average of 140%, with 70% of the lambs going to the works straight off the ewe, which Andy says is a great way to farm sheep and an incentive to focus on a quality feed programme for both the bulls and sheep.

“What it boils down to is doing the basics well.”

Pinch time is mid-August to mid-September, so the right balance of stock is a huge benefit.

Expenses in the 2020 year were sitting at about 42% of the gross farm income, which is a culmination of good prices, efficient feeding, turning stock over at optimal times, and keeping a close eye on body conditioning.

“We draft out the bottom end and run them on better feed if we need to.”

Contrasting seasons is the biggest challenge of farming in the region and makes planning hard.

It’s hard work and to make it profitable Andy is constantly asking himself, “How can I make it better?”.