Clear vision and robust plan needed

If you haven’t got a strong looking at succession, you are not going to have many options to make it work, Peter Flannery writes as he starts to look at the four pillars of successful succession planning.

There are four pillars to building a successful succession plan.

They are:

- Build a strong business first.

- Communication with family.

- Fair comes before equal.

- Transfer of ownership and control.

The first of those pillars. If you haven’t got a strong business when you are looking at succession, you are not going to have many options to make it work.

So what does a strong business look like? First, it has to have scale. A business generating $1.5 million of income is going to have more options than one half that size. Every business has fixed overheads, regardless of size. The biggest fixed cost is personal drawings. Your drawings are not a function of the size of your business. They are a function of your lifestyle and your own family’s size, stage and age.

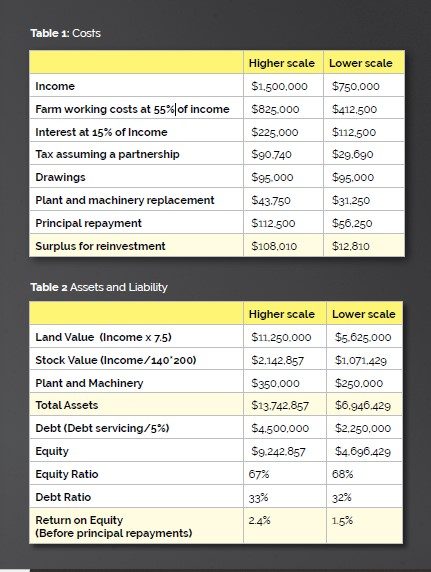

Table 1 shows two businesses, one with twice the scale and both drawing $95,000 for personal expenditure. If we assume farm costs and debt servicing are in similar proportion to income, then after tax, plant and machinery replacement and principal repayments, there is a stark difference in the cash available for investment.

In this simplistic example, the business with twice the scale generates $100,000 or nearly 10 times more available cash surplus for investment, thereby providing more options for succession.

So the amount of free cash generated within the business is key, however we should also look at the balance sheet. This is also impacted by scale. The larger the scale, the more borrowing power a business will have. If we extrapolate out the above and make some assumptions, the respective balance sheets may look like Table 2.

Not surprisingly in this example the equity is nearly double in the larger scale business, both with similar debt and equity ratios.

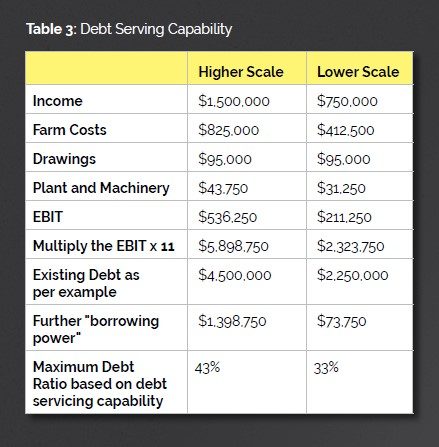

However, the harsh reality is that the larger scale business has a lot more borrowing power. To be “bankable” a business needs to be strong enough to generate enough “free cash” to repay its debt over 20 years. At current interest rates, this equates to around 2.5% of total debt borrowed. Bear with me while I get a little bit technical. To be able to achieve this, the business needs to have a debt to EBIT ratio better than 11. This is a reasonably “modern” measure, and at least one bank uses this as their criteria to assess credit risk (Table 3).

Given the profit and loss of the two businesses in this example the lower scale business is pretty much fully lent whilst the larger scale business can most likely increase its debt ratio to 43% meaning it could potentially borrow another $1.4m. The harsh reality therefore is in this example the lower scale business has very few options. With $4.7m of equity, at 68% of total assets, what would appear to be a bankable business in its current state has very few options to remove capital from the business to allow for succession.

Scale on its own though is no cure-all.

A business will not succeed or fail just because of scale or lack of it. It is what you do with your scale that is the key. The above example assumes that other than scale all things remain the same. Which generally is not the case. Management and governance remain the key.

As the business grows governance becomes increasingly important. In boxing parlance, a good big man will always beat a good smaller man. But size without skill is a weak and possibly overconfident combination and is unlikely to succeed.

Other than scale, a strong business needs to be managed and governed at a high level. Scale, particularly significantly large scale can lead to a loss of attention to detail and an increase in waste. So if your income is say $3.0m, and farm working costs sit at 65% and debt servicing at 25% then 90% of your income has been spent, before drawings, tax, plant and machinery replacement. A business in that situation should be focusing on survival rather than worrying about succession.

As the scale of a business increases and as the number of staff employed increases, the greater the need for the owners to have strong employment skills. The ability to employ the right people, develop, train and retain them becomes just as, if not more important, than day-to-day farm management skills.

I often get asked, should we be building off-farm assets? My answer has always been, will it help build a stronger business? If the business is generating “free cash”, what should you do with it? Most banks will require you to be repaying some principal but what should you do with the rest?

The trap is to lift your lifestyle, and see your drawings lift accordingly. If you are disciplined though, you have two choices. Increase the rate of debt repayment or invest elsewhere. Developing the farm to its optimal level will generally always provide a return better than the cost of interest. However, if the farm is already well developed, what next?

Buying adjoining land or land that adds balance or strength to your existing business has always been a good move, particularly if you are growing from a position of strength. However, buying land “just because you can” is not necessarily the right thing to do. Always understand your “why”. What is your long-term plan?

So, what to do?

Buy more farming assets or off-farm assets? The advantage of investing away from farming is that when the time for succession arrives you will have assets that can be sold or transferred without impacting on the existing farming business. However the two critical considerations for this strategy to be successful are:

- Understand and be very interested in whatever it is you are investing into, and secondly it should not put at risk your core farming business.

- Building strong businesses generally doesn’t happen by accident. You need a clear vision, a robust plan to achieve it and a strong desire to be the best you can be. Know where your strengths and passions lie and invest accordingly.

Peter Flannery is a Southland and Otago-based agribusiness consultant who has 20 years’ rural banking experience. He started his own company Farm Plan 10 years ago facilitating families and their businesses through a business succession process.