Borrowing: Whose risk are you managing?

With interest rates turning up after years of trending down, Victoria Rutherford looks at the options with borrowing.

With interest rates turning up after years of trending down, Victoria Rutherford looks at the options with borrowing.

When you’re fixing your interest rate it pays to ask the question – whose risk are you managing? Significant differences in longer-term fixed rates between banks indicate some providers are taking a pessimistic view of risks, which could in turn add significant cost to the farmer.

Timaru-based director Andrew Laming from New Zealand Agri Brokers (NZAB) says they’ve been having discussions with their customers recently about fixing interest rates, given the increase in rates via recent OCR changes.

Until recently, the downward trend of floating interest rates has made them the product of choice. However, expectations are now up rather than down, with most economists plus the RBNZ forecasting further rate increases.

Laming says they are seeing those expectations played out in the swap curve, where five-year swap rates have moved from historical lows of about 0% to a peak of about 2.8% recently. He goes on to highlight the significant discrepancy between banks at present with their various fixed rates, even when standardised back to the same customer margin.

“What’s happening between the four banks is that you’ve got different expectations about what margin they might require in the future, to justify continuing to lend the capital to the farmer.”

“Historically, we don’t typically see such a big difference between banks across the terms, but given the big gap opening up and customers looking to make fixing decisions right now, we thought it would be useful to point this out,” he says.

Laming says the way bank loans are priced these days are complex.

“There’s the cost of the money, both domestically and offshore, but also, it’s the bank’s view of the future risks that might impact on their own return. Uncertainty over future reserve bank regulatory capital amounts, the growing impacts of climate change and the volatility of farm returns are all now having a negative drag on margin.

Added to this are the more traditional impacts – the bank’s internal portfolio ratings, the level of good and bad loans and whether they are in growth or retrenchment mode. All of those things combined, make up a bank’s margin.”

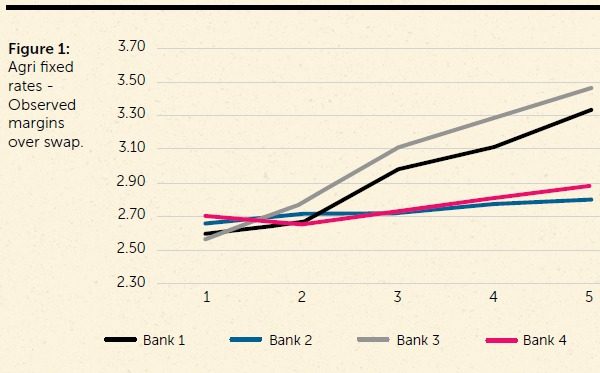

Figure 1 shows data from the four main banks depicting the margin above the swap rate for each term of one-to-five years. NB:

- This is based on a customer base margin of circa 2.5 basis points above a typical bank market bill rate (BKBM) for illustrative purposes only.

- The colours of the graph are meaningless versus the normal colours of the main banks.

- This is only one data point and only one consideration out of many when discussing and then agreeing on an interest rate risk management strategy.

Laming says the numbers in this case are extremely stark.

At one-to-two years, most banks adopt similar margins above the swap curve as each other.

“However, when we move out to three-to-five years, two banks in the marketplace have significantly higher margins inserted in their three-to-five-year rates than the other banks.”

He says at their broadest gap – the five-year rate, those margin differences are as much as 65 basis points. To put that in context, that means $6500 per year per $1 million locked away. That means $32,500 over five years.

“If it was a $10m loan, that would be $325,000.”

He says this premium is above and beyond the market, and ultimately does nothing to manage the borrower’s risk.

What causes the difference in rates?

The difference in rates can be caused by several things, but Laming says the major reason is the banks’ differing views around the required margin changes that they might need to make in future if (a) a customer’s credit risk changes or (b) RBNZ capital regulations change.

“When a bank locks in a fixed rate with you as a borrower, the margin and their return with it is generally locked in for that period of time.

“If the amount of bank capital that they hold against your loan needs to change in the future (due to credit risk or regulatory changes) and that impacts on their return on equity, then they can’t do much about that if there is a fixed margin in place.”

Therefore, uncertainty about the future results in a bank attempting to manage this risk with various margin buffers and views on what the future may hold.

He says some banks are a bit more uncomfortable about locking away that fixed level of return, given things might change in the future that might impact on that return.

“In other words, they’re managing their own risk at the same time, by transferring that risk on to borrowers. Clearly some banks have a much different view of that future than others.”

Andrew says this should not be a deterrent to making a fixing decision as the highlighted data point is only one consideration out of many when discussing and then agreeing on an interest rate risk management strategy.

“With fixing versus floating, it’s a risk management decision, but often it is clouded with a bit of emotion, and what I mean with emotion is fear.

“The reason that people start talking about fixing interest rates is to manage risk, but also it’s because they’re scared that the floating rate’s going to go higher, and that’s entirely valid.

“Immediately they then go to the bank and go, what are my fixed rates? They’re trying to manage that fear or that risk that rates will go up. Now, inadvertently, particularly when you get to three to five years, you may be locking in significant additional margin, which goes beyond just managing your own risk.

“In other words, the borrower is paying a premium, which probably sits above what is necessary, and it defeats the purpose to some degree, of what they’re attempting to do.”

Market forces will likely sort out the discrepancy in time.

“Like most things in our market, you can’t remain an outlier for too long because competitive forces drive that back into the middle.

“But that doesn’t mean that all rates will come down. It might mean some of the other rates come up.

His advice for farmers looking to fix interest rates is to seek advice around what the banks are offering.

“A wider discussion needs to happen between farmers and their professional advisers about all the components of risk in their business and how they might build a plan to manage them, aside from their banks. Those that get that right will enjoy very good ongoing margins from their bank”.