Tony Leggett

Research just released from an on-going ewe longevity project shows a strong relationship between body condition score (BCS) at mating and wastage, either from premature culling or mortality.

Massey University veterinarian Kate Griffiths is not surprised by the strength of the relationship or the outcomes for low BCS ewes, which are more likely to be culled because they are either dry at scanning or wet-dry at docking, or else dead in the paddock.

What is puzzling her is why more farmers are not checking body condition score (BCS) more frequently, then separating those lower-condition ewes to preferentially feed them.

“I’m surprised at the number of farmers that are put off because they think it’s too hard to do a BCS, or it’s too time consuming when it’s actually very easy and quick,” she says.

“You don’t really have to assign an actual score to each ewe. You just decide if she is a tail-end ewe and draft her off for better feeding. That is usually the best use of short available feed,” Griffiths says.

‘Farmers are usually making culling decisions at one point in time for the entire flock, often with very limited knowledge of the past performance of each animal.’

In the Massey University research, post-mortems carried out on ewes with a BCS of two or less showed many did not have any significant disease and may well have responded to preferential feeding.

She advocates running all ewes through a BCS at least twice in the year – firstly after weaning to ensure ewes gain BCS before mating and then at scanning.

“Farmers could combine an udder check and a BCS a few weeks after weaning to avoid yarding mobs twice.”

It is important for each animal to be assessed by placing a hand on their back. Visual assessment as they come down the drafting race is notoriously inaccurate at peeling off the tail end ewes in a mob.

“In our research, we work on 600/hour and that is a BCS, weighing each one in a crate, and recording the data. So for just BCS, a typical farm could work on much more than that number per hour.”

Culling decisions are almost always implemented across entire flocks, not individual animals, leading to higher wastage rates, Griffiths says.

“Farmers are usually making culling decisions at one point in time for the entire flock, often with very limited knowledge of the past performance of each animal.”

“Farmers are usually making culling decisions at one point in time for the entire flock, often with very limited knowledge of the past performance of each animal.”

Culling at five to six years of age, regardless of a ewe’s past and potential performance, is not uncommon. But it could be costing farmers to make these broad culling decisions if that ewe is performing strongly and retaining her could reduce replacement rates.

In the project flocks, where nearly all were mating ewe hoggets, many of these young sheep never made it into the mature ewe flock as two tooths after being culled for either not getting in lamb or failing to rear their lamb or lambs.

A subset of data looking specifically at mated and pregnant ewe hoggets highlighted the success in rearing a lamb was influenced by body weight, BCS and weight changes during pregnancy.

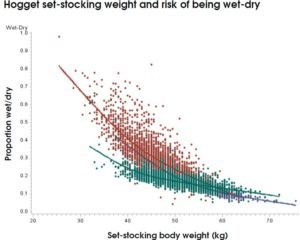

Across all the flocks in the project, Griffiths found that as ewe hogget weights at set stock reduced, the risk of wet-dries increased dramatically (see graph).

What did vary across flocks was the optimum weight. But, as a rule of thumb, the heavier the hogget is at set stocking the more likely she is to rear a lamb through to weaning. Hoggets that lost weight between scanning and set stocking were much less likely to rear a lamb.

“Weight is important, so the hogget needs to continue to grow by 100-150g/day throughout her pregnancy, and that’s also allowing for the gain in weight from the lamb or lambs inside her.”

“We found that for every 1kg gained in body weight between scanning and set stocking, there is a 10% reduction in likelihood of that hogget being a wet-dry,” she says.

Griffiths says she has been contacted by many farmers seeking answers to questions they have raised after attending her recent presentations.

“I’ve had a lot of emails and phone calls from farmers. Most want to know what they can do about the wastage level; others were concerned about the potential animal welfare risks if ewes are dead in the paddock,” she says.

NZ flock mortality rates are similar to hill country flocks in other countries like Australia or the United Kingdom, and are similar to the rates recorded in NZ during the 1960s and 70s.

Further research in this project will also focus on the reasons for ill thrift in ewes and how they respond to priority feeding before going back into the flock.

This followed the post-mortem results from the ill-thrift ewes selected at scanning time on poor BCS.

“The post-mortem results showed us there was nothing wrong with many of them so they would have responded well to preferential feeding.”

“The message here could be to draft off light ewes and preferentially feed them. If they don’t respond, then make a call on keeping or culling.”

Given the rise in average lamb prices, the potential for high scanning performance and the reduction in electronic ear tag prices, Griffiths suggests it might be economic for ewes to be tagged so their performance is carried with them and used to make more informed culling decisions.