BY: KERRY DWYER

New Zealand sheep farmers have been part of a major structural change to their industry over the past 30 years as wool use and prices plummet. Wool has declined in relative importance and sheep meat has gained prominence. Sheep numbers have dropped while lambing percentage and lamb weights have increased.

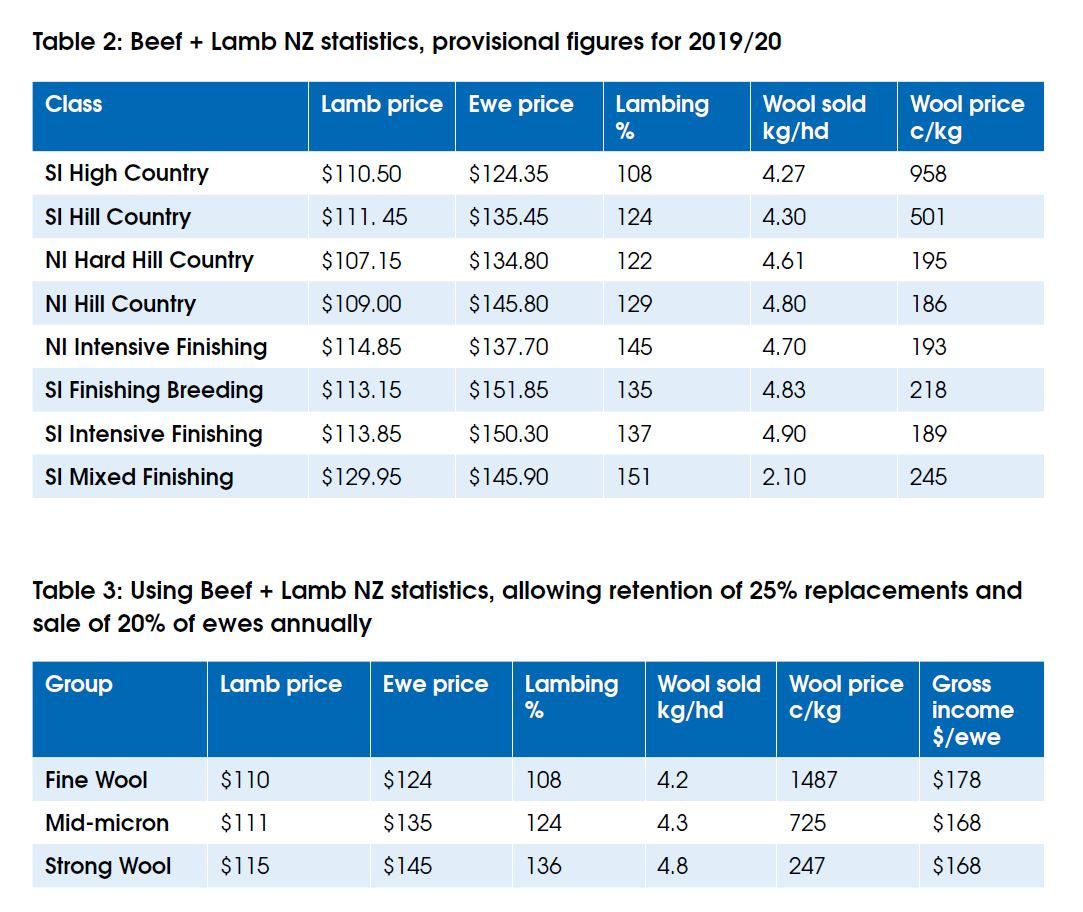

Table 1 shows a comparison of prices, importance, and shearing costs at four points over the past 30 years. I have sourced August pricing for each year where possible. Note that there have always been fluctuations within and between years and variation in different areas of the country. Overall, the trends are very clear.

Wool prices are below the cost of production, which is not sitting well with many sheep farmers. Our expectation is that we should be able to grow and harvest wool at a profit although that may not be the case for many (or most) sheep farmers around the world. The relativity between wool prices and harvesting costs is out of kilter, and by no means am I saying shearing is too expensive. I have shorn enough sheep not to begrudge the workers their pay. On our farm I make sense of the equation by shearing the sheep myself, which is not a viable option for most f armers. But having been offered 30c/kg for Suffolk fleece wool I am thinking it might have more value as fertiliser and have put some on the garden since it is cheaper than straw.

Note the shearing cost listed is the shearing and crutching bill for the year divided by kilos of wool produced per farm as per industry figures. This will be higher for fine wool sheep but we are concentrating on crossbreds.

No wool

Most crossbred sheep farmers will be losing money on wool production to the extent of the difference between shearing costs and wool price. From Table 1 that looks to be about $1/kg, which means over $15,000 per year for the average sheep flock. If you have sheep which do not need shearing then it could be argued you will be better off by $15,000 or more.

Which begs the questions – what is the cost of production, and what is a price required for sustainable production?

The cost of production needs to cover shearing, animal health, breeding and feeding costs. Given shearing at $2.20/kg wool; add maybe a quarter of the animal health bill (25c/kg wool); add some cost for wool genetics (15c/kg wool); and maybe a feeding cost to cover a percentage of real cost ($5/sheep/year or $1/kg wool). That totals to a cost of production of $3.60/kg wool.

Therefore an average sheep farm may then be better off by $54,000 by having sheep with no wool, being without the cost of 15,000kg of wool at $3.60/kg. The main assumption for that is energy put into wool production would be channeled into meat production, which will depend on genetics and management.

Wool production has not been sustainable in New Zealand over the past 30 years as evidenced by the 55% decline in total production. We need to add a profit margin of 40% to the cost of production to get a figure that may encourage sustainable production. Based on the premise that farm costs sitting at 60% of income allows sufficient margin for a normal farm system, so $6/kg is required. Inability to reach an adequate return has seen many woolsheds used for other purposes in the past 30 years.

I have mentioned Bioclip before, which was an injection promoted to cause wool shedding about 15 years ago. While not a commercial success, the injection cost of about 80c/sheep at the time looks to be attractive at about 10% of today’s shearing costs. Many activists abhor physical shearing of sheep, so don’t jump to the conclusion that an injection would not be acceptable management in the 21st Century.

Less emphasis on wool

Most sheep farmers around the world appear to accept that shearing is an animal welfare issue for sheep. They get it done and don’t begrudge the shearer, or maybe they do it themselves (with a pair of scissors).

Sheep Improvement Limited’s (SIL) dual purpose maternal index puts about 7% emphasis on wool production. If you are selecting your maternal rams on that index then you have agreed to less emphasis on wool and more on lamb production. If you put all selection pressure on lamb production then the ultimate is a meat breed sheep. Looking at the Central Progeny Test results from Beef + Lamb NZ genetics it would appear that the best terminal sires are more than a $1/head better at meat and growth than the dual purpose sires. Extended over the average sheep farm that could mean an extra dollar per lamb per year owing to genetics.

The range of genetics within breeds and breed groups is likely to have an even greater benefit. For example, an average 50g/day improvement in pre-weaning lamb growth is likely to have an immediate benefit of $15/head at weaning, or greater than $20,000 on our average sheep farm.

More and better wool

Growing and preparing better wool has a cost, and readers should calculate whether they get adequately rewarded for the effort. Refer to the estimated cost of production and required sustainable price I gave above. Having the best product to sell at a loss doesn’t make long-term sense.

There are farmers who have moved to half-breds or Merinos to get a better value fleece.

Thirty years ago the emphasis of crossbred wool production was on fleece weight. I can remember being mocked in the 1980s for using a Corriedale ram over Romney ewes to get a finer stylish fleece. I have recently heard this being suggested along with a general move to fine up the clip to give more potential end uses.

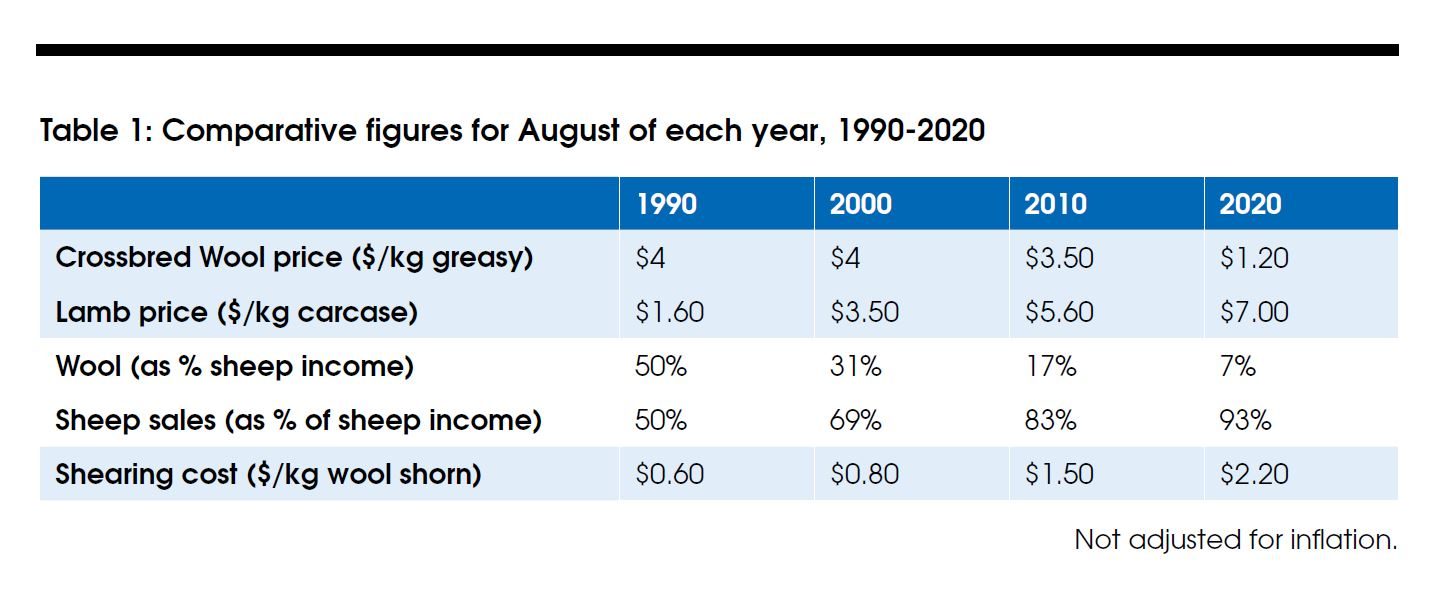

Analysis of the economics of a breed change (see Tables 2 & 3) generally shows there is not much benefit when an increased wool income is countered with a loss of lamb production. The key is to get the best out of the finer-wooled sheep rather than relying on just the fine wool.

Merinos have not been bred to count that well, so some genetic push is going into breeding a fine wool ewe that can do better in lambing and lamb growth. Breeding has made huge leaps in giving us a fine-wooled sheep with a fleece capable of handling wetter climates. Animal health has been a weak point for such sheep in wetter areas, which is why they were displaced about 150 years ago to the drier ends of New Zealand. I am seeing great results from Footvax to mitigate footrot and, with more breeding selection, we may see a move to finer-woolled sheep.

Referring to Table 1 above, the trends for finer wool have been similar to crossbred wool in terms of reducing importance to overall sheep income. I have clients shearing Merino hoggets with over half the wool cheque required to pay harvesting costs, while two years ago the relativity was closer to 20% for harvesting costs.

Summary

There are onfarm options for every sheep farmer. You make the decisions on your investments of time, effort and capital.

Much of the discussion relates to off-farm options for wool in the face of a rapid devaluation of the product. Farmer involvement in off-farm wool matters has generally been politicised rather than commercialised, and farmers have shown a reluctance to invest off-farm. By comparison, many farmers have considerable investment in the meat or milk processing and marketing industries – to reach a similar commitment might require wool growers to invest between one and five years of wool income.

- Kerry Dwyer is a North Otago farm consultant and farmer.