Better cattle handling: For people, product and perception

Multi-pronged benefits can come from low-stress cattle handling (LSH) such as improved operational efficiency, enhanced meat quality, and a safer working environment for farmers according to a 2024 Kellogg report. Words Sarah Perriam-Lampp.

Historically, many farmers develop a deep understanding of cattle behaviour and movement through observation from their farming childhood. Iain Inglis has found that both age and experience doesn’t trump a lack of early exposure to this skill in what he sees is a reliance on fear-based cattle-handling techniques that has creeped in over generations. His 2024 Kellogg report highlights increased stress levels in cattle is what is driving poor cattle-related injury statistics and poor quality meat. Iain Inglis has, like many who work with cattle, been involved in sheep and beef farming his entire farming career and it has been as much hands-on farming as it has corporate. Like his farming peers, he too developed ‘stockmanship’ skills from a young age.

Iain currently manages the ANZCO Five Star Beef Feedlot where he has been working with the methods of Low-stress Cattle Handling (LSH) that underpinned his interest for his Kellogg research report.

“I travelled across America for my research as well as reviewing literature from New Zealand and around the world on LSH which is a fascinating topic with multi-pronged benefits,” explains Iain.

His report focuses on three opportunities that come from LSH – improved operational efficiency, enhanced meat quality, and a safer working environment for handlers.

“Cattle handlers have somehow lost their slow observational wisdom and reverted to a natural tendency of using fear and predator-type aggression. Shouting, whistling, using sticks and forcing animals from behind. This behaviour increases the risk of injuries to both people and cattle and is resulting in devalued product opportunity.”

Isn’t LOW-STRESS HANDLING just good stockmanship?

Low-stress handling is used and confused with the term ‘stockmanship’. According to Tom Noffsinger, a US feedlot veterinarian known for his passion and enthusiasm for working with feedlots and ranches on low-stress cattle, low-stress handling is a more advanced practice of stockmanship.

“Just getting the cattle to move and do what you want them to do, that’s stockmanship,” explains Tom. “LSH is a higher form of stockmanship with techniques that guide cattle calmly and effectively managing the animal psychology and wellbeing.”

“Shouting, whistling, using sticks and forcing animals from behind. This behaviour increases the risk of injuries to both people and cattle, resulting in devalued product and people leaving the industry.” – Iain Inglis, 2024 Kellogg scholar

It may not seem like rocket science to those who have worked with cattle their whole life, but with over 4,000 cattle-related injury statistics each year in New Zealand according to ACC, Iain says we still have a long way to go. There is a belief that high-stress handling culture has gradually become part of modern cattle handling due to the names of parts of the cattle yards such as ‘forcing’ or ‘crowd’ pen as common terms.

Livestock value of LSH

Livestock value of LSH

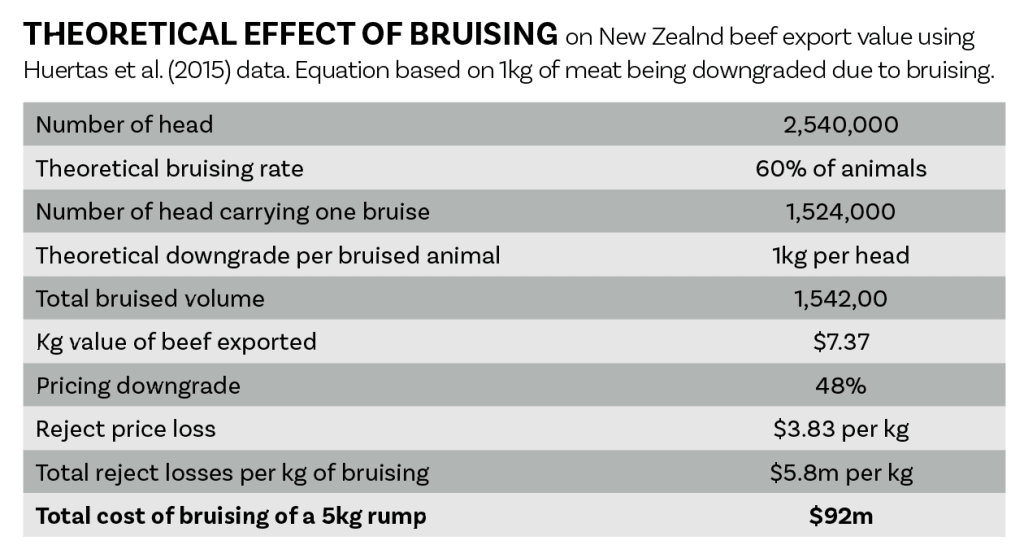

The rubber hits the road in Iain’s report when he breaks down the production benefits having a tangible economic effect as the animals have improved ability to put on liveweight gain and convert feed efficiently when they are not stressed. The reduction of any incidence of disease and injury is also noted as well as the impact on meat quality including parameters such as meat colour, pH levels, and eating quality. Value for the beef producer is not gained solely through the sale of the finished carcase. New Zealand’s beef cow-calf/breeding operations regularly trade livestock including weaner calves, mid-aged store cattle, and sire bulls with many movements throughout their lifetime.

“Training and preparing cattle to be separated from their mothers is a great opportunity and has positive returns when it comes to performance and health over their lifetime,” states the Kansas State University Beef Cattle Institute (KSUBCI, 2022) who advise low-stress handling to minimise shrinkage in young calves.

Although the institute suggests 2–3% shrink is unavoidable, levels above 5–6% are possible when calves are poorly handled. In their example, a 500lb calf is calculated to lose 25lb. With just under one million beef breeding cows producing a calf each year in New Zealand (Beef + Lamb New Zealand, 2023), Iain states this is a significant potential cost to producers.

In a New Zealand saleyards system, animals have multiple experiences with people in a very short time. Regarding this saleyard process, Iain says it is worth linking KSUBCI’s (2022) calf shrinkage statistics with Lukasiewicz’s (2024) point that cattle remember each encounter with people. Iain states that there may be a significant opportunity to review the livestock selling process against low-stress handling principles and outcomes. In his report he provides comprehensive suggestions on how to improve cattle-handling training across the industry.

Typical NZ cattle movements

A typical process for the animal travelling from one farm to another via saleyard could be:

- Move to yard/loadout area from paddock

- Check/scan identification tags moving cattle through a race

- Load onto truck

- Travel to saleyard

- Unload from truck and move to holding pen

- Move from holding pen to selling area

- Auction process with auctioneer calling for bids

- Move back to holding pen

- Move to loadout area

- Load onto truck

- Travel to farm

- Unload from truck

- Receive animal health treatment

- Move to paddock