Beefing up production

A good beef herd is crucial for lifting pasture quality for sheep, reckons King Country farmer Alan Blake. Story and photos by Mike Bland.

A good beef herd is crucial for lifting pasture quality for sheep, reckons King Country farmer Alan Blake. Story and photos by Mike Bland.

Behind every great ewe there’s a great cow.

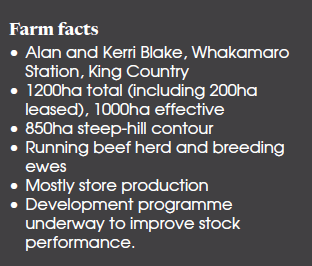

That’s definitely the case on Alan and Kerri Blake’s Whakamaro Station in central King Country, where sheep performance has lifted markedly in recent years, thanks in no small way to cows.

While increased soil fertility, better stock management and genetics are other key factors, Alan Blake says a good beef herd is crucial for lifting pasture quality on steep hill contour.

“Cows groom pastures for the ewes and help us get more production out of the sheep.”

The Blakes winter more than 10,000 stock units, including 5000 Perendale ewes and 350 Angus-Hereford cows on 1200ha at Otunui, south west of Taumarunui.

Alan’s parents Jim and Lindsay and his uncle and aunty, Tom and Heather, bought 1000ha Whakamaro as part of a succession plan in 2013. Alan and Kerri leased the farm until buying it in 2018. They also lease another 200ha block nearby

Whakamaro’s effective area includes 30ha of easy-rolling contour, 120ha of medium hill and 850ha of steep hill. The balance is mostly native bush.

When she’s not helping out on the farm, Kerri, a Massey University graduate with an impressive range of qualifications, works three days a week in Taumarunui as a support staff member for VetEnt.

She and Alan have two sons, Archie, aged five, and Finn, 3.

The Blakes employ full-time shepherd Aidan Jury on Whakamaro, and Alan’s father Jim is always happy to help out.

Alan, who has worked on a range of different farm types both in New Zealand and the United Kingdom, says he and Kerri prefer hill country farming because they like a challenge.

Whakamaro’s steep contours can certainly test the spirit of man and beast. The main cause of cattle loss is misadventure – animals falling off bluffs or down steep slopes. About 20 cows die this way each year, despite improved fencing.

Sheep losses through misadventure are much lower, something Alan attributes to the mobility of the Perendale ewes.

“Perendales can be frustrating at times but they are very hardy and they have no problems getting around the hills and bringing the lambs in.”

Three years ago the Blakes started a development programme designed to help them reach a target of 180kg of product (meat and wool)/ha.

Capital fertiliser was a vital ingredient. The farm had high Olsen P levels on the small area of easy contour but only 3 to 6 on the hills.

Following advice from fertiliser consultant Doug Edmeades, the Blakes decided to lift P levels to 10-12 on the hill country. In 2019, 550kg/ha of superphosphate, along with some potassium, was flown on to the hill country. Alan says the application included 250kg of capital fertiliser, which cost about $100,000.

They borrowed the money to do it.

“Instead of spreading capital applications out over several years we decided to do it in one hit so we’d hit optimal P levels faster.”

That decision paid off. P levels in the hill country are now within target range and Alan says the farm is growing a lot more grass, particularly on the shoulders of the season.

Production is now trending upwards – from 140kg/ha (meat and wool) in 2018 to 154kg/ha in 2021.This year the farm is on track to reach 160kg/ha.

Fencing and water reticulation have been other key priorities.

Alan says they’ve invested about $120,000 into new water systems and troughs over the past five years. This includes the recent installation of a solar-powered water pump which pumps water from four natural springs and delivers it up to three water tanks with a combined 90,000 litre capacity. Water is gravity-fed from these tanks to 300ha of the farm.

About 70% of Whakamaro’s 110 paddocks now have troughs and this has significantly reduced the farm’s reliance on natural water. The aim is to get reticulated water to 90% of paddocks.

Since 2013 the Blakes have replaced a lot of old fencing, adding about 1-2km of new fencing annually. The largest paddock is 134ha, making it a challenge to muster, but Alan hopes they can eventually split this paddock into more manageable chunks.

Farm access has been improved and yards have been upgraded. Weed control is ongoing and about 40ha of scrub is cut and sprayed each year, along with 60ha of ringfern.

Feral goats are controlled through an annual culling programme. Alan says he shot 1300 in the first year “because mustering them was getting us nowhere”.

Hardy cows handle hills

Whakamaro’s mainly Angus-Hereford beef herd has been built from scratch as there were no cows on the farm when the Blakes began leasing it in 2013. They started with trading cattle and gradually built up cow numbers.

Alan jokes that he likes the whiteface cattle because they are easier to spot in the scrub.

But the cows are ideally suited to the contour, and their crossbred calves show the benefits of hybrid vigour and are highly marketable.

He says Angus-Hereford cows have a quiet temperament and this is important because they only come into the yards about four times a year.

Young cows grow up on the easier contour, where they are mated at 300kg-plus and calved behind a wire. Mixed-age cows are set stocked with the ewes in the hills at about 1 cow/3-4ha from August to January. They calve in the hills from November.

This year 300 mixed-age cows went to the bull, along with 67 first-calvers. All replacements are bred on the farm and surplus heifers are sold in August at 15 months.

Most steers are sold as yearlings at 400kg liveweight (LW) average.

The Blakes buy one Angus two-year bull and one Angus yearling bull every year from the Puke-Nui Angus Stud, and a Hereford every two-three years from Craigmore Polled Hereford Stud.

Bulls are selected for calving ease and growth rate. Alan prefers smaller bulls.

“We don’t want anything over 1000kg because they would struggle in the hills.”

Alan says ideal cow weight is about 500kg. Heavier cows would be less efficient and more prone to misadventure.

Calving efficiency is about 80-85% calves sold/cow wintered, and the aim is to get steers to 220kg and heifers to 200kg by weaning.

“At the moment we are averaging about 190kg at 150-days, but we are able to feed them a little more each year.”

This year about 80 steers were sold in early November instead of December.

“I told our agent I wanted $3.80/kg for the steers and he said ‘I can get that now’, so off they went. That’s helped us put more grass into the heifers.”

About 84 heifer replacements were retained this year.

Whakamaro’s present sheep-to-cattle ratio sits at about 70:30, but Alan says this is likely to shift towards 60:40 in future. “Because we are growing more grass, we’ll need more cattle to maintain pasture quality”.

Strong store country

Alan and Kerri Blake don’t see the farm’s lack of finishing contour as a weakness. Instead they focus on its strength as a producer of healthy store lambs, steers and heifers.

Alan says the district has a good reputation for producing lambs and cattle that finish well. These animals are keenly sought after by finishers in regions like Hawke’s Bay and Wairarapa.

Store lambs typically provide about 60-70% of Whakamaro’s income. Lamb sales this year will contribute about $600,000 to an estimated gross farm income of $900,000.

Alan says a huge chunk of this income is generated over the space of just four weeks – between December 14 and January 14 – when about 700 cull ewes and 4000 store lambs go.

“We drop about 4000 stock units straight after weaning in December. It puts a big smile on my face when I think of the income coming in, and it takes a lot of the pressure off the farm for summer.”

After Christmas about 3000 lambs are left, including the ewe replacements.

Alan says while being a store lamb producer means “you are at the mercy of the market”, he takes a proactive approach to lamb marketing. Livestock markets are carefully monitored, particularly in the regions where most Whakamaro lambs traditionally go to.

“I also keep an eye on weather reports, especially in the Hawke’s Bay, Manawatu and Wairarapa, because the weather obviously has a huge influence on demand for our lambs.”

He works closely with livestock agent Richard Bevege, NZ Farmers Livestock, to maximise lamb value.

“I could sell lambs direct but I like to use an agent because it’s worth it in the long run. I tell Richard the price I want and I know he’ll do his best to get it. An extra 5c/kg can make a big difference when you are selling a large number of lambs.”

Whakamaro usually finishes about 800-900 lambs off-mum at 16kg carcaseweight (CW), but this year only 500 were finished due to a lack of processing space. Mixed-sex lambs sold store before Christmas averaged $107/head – a big improvement on the $80/head achieved the previous season.

Most lambs go at 29-30kg, although this can vary from year to year. Alan says a key goal is to increase 90-day weaning weights to a “consistent 30kg for maternal lambs and 32kg for terminal lambs”.

He’s never been afraid of seeking advice from professional sources. For the past six years the Blakes have used VetEnt’s StockCare farm improvement programme to help them make key farm management decisions. Sheep are condition scored and key performance indicators, like scanning, lambing and docking percentages, are carefully monitored.

Three years ago, vet William Cuttance suggested they adjust their lambing dates to improve lamb growth.

In 2013-14, their first season on Whakamaro, terminal-mated ewes lambed from August 10 and the maternal ewes lambed from August 20.

“Will suggested we slide lambing back 10-14 days, so last year our terminals lambed from August 25 and the maternals from September 5.”

Alan says they like to try “small changes every year”. In 2022-23 the maternals and the terminals will both lamb from September 5.

He says the terminals haven’t performed as well as expected over the previous two years, so the switch in lambing date is designed to better match pasture growth.

“In the past we’ve split lambing dates to spread risk and the workload, but this year we’ll lamb them at the same time to see if it makes a difference to ewe performance and lamb weights.”

Ewes are run in four to five mobs of 1000-1100, with about 200 tail-enders farmed separately to boost condition.

The Blakes aim to get as many ewes as possible to condition score (CS) 3 for mating and lambing.

“Last year we had heaps at CS4 but there was no noticeable production gain.”

Hoggets aren’t mated but the Blakes still try to get them to a minimum of 40kg by May.

Alan says hoggets “never see a flat paddock” but perform well in the hills. Any sheep that gets daggy or shows signs of ill-thrift is moved to the terminal mob.

Lifting two-tooth weight

A crucial part of the Blakes’ plan to improve ewe production is to increase the weight and frame size of two-tooths. Alan says the goal is to reach 60kg by mating time. This has been achieved over the last two years.

“The farm is growing more grass, so we can put more into them. It’s a fine line between production and development and we don’t get it right every time. One year we robbed the hoggets to feed the ewes and that backfired on us.”

The region has had two dry years in the last three, but Alan doesn’t like to use drought as an excuse for missing targets.

“We don’t plan for a drought every year. That’s how you miss opportunities.”

Lambing performance has improved steadily since 2013’s 94% (ewes to ram). Last year’s lambing reached 134%, tantalisingly close to the Blakes’ goal of achieving 135% “consistently in good and bad years”.

Alan puts the lift down to better feeding and genetics.

“One of the advantages of the monitoring work we do through the StockCare programme is that we know if we are heading in the right direction. We’ve still got improvements to make but I think we’re developing a recipe that works.”

Ewe wastage dropped from 5.9% in 2017 to 3.6% in 2021, which Alan again attributes to pasture growth, improved subdivision and good genetics.

Building facial eczema tolerance has been a key priority for the Blakes who source FE tolerant Perendale rams from Raupuha Stud and Coopdales from Nikau Coopworth Stud.

This year they started their own recorded flock, using 30 ewes and 15 hoggets from Raupuha’s Russell and Mavis Proffit, who have been supplying Whakamaro for nine years. These sheep were selected for their high EBVs for FE tolerance, growth and fertility.

The farm will run 150 recorded ewes this year, all farmed in the hills with the other ewes.

While the stud adds work, Alan says livestock breeding has always been an interest.

He wants to breed a ewe that is perfect for steep hill contour. Once the stud is established it could add an income stream in future.

Forestry is another form of diversification and this year the Blakes will plant 70ha of pines on the farm’s least productive land. The plantation will be registered under the Emissions Trading Scheme.

“It’s only 7% of the farm, but we will double what we make off it now.”

Looking after the river

Alan and Kerri Blake are founding members of the Otunui Valley Catchment Group, which comprises about eight farms in the region.

Alan says the group has been monitoring water quality for 18-months and hopes to include more farms in future.

The Whakamaro River, a tributary for the Whanganui River, runs through Whakamaro Station and the Blakes have planted about 2km of their 5km stretch so far.

Kerri, who has a Certificate in Horticulture, recently started their own nursery to produce natives for further planting and possible sale in future. She says the nursery has capacity for about 8000 riparian plants, including kowhai, flax and tree lucerne.