BY: VICTORIA O’SULLIVAN

When we think of crop pollination we automatically think of honey bees and hives. But what role do other insects that visit flowers play in pollinating clovers, brassicas and seed crops?

Research has shown they could, in fact, be providing pollination for free.

Over the past several years, the Foundation for Arable Research (FAR) has been working with Dr Brad Howlett and Dr Melanie Davidson at Plant and Food Research to find out how effective some of the other common crop visitors are as pollinators, and to see whether they can be supported by establishing biodiversity plantings.

FAR environment research manager Abie Horrocks says brought-on bees are like irrigation – they have an important role to play but they come at a cost. Alternative pollinators, however, are like rain – they come for free. On top of this some insects can provide further benefits, attacking pest insects such as aphids and caterpillars.

Some insects will pollinate when honey bees aren’t active such as on cool, cloudy days. Others can help pollinate the crop in the situation where honey bees vacate for a preferred crop over the fence. For example, many flies love carrot flowers but they are not a preferred flower for honey bees.

The study found New Zealand’s native bees and bumblebees pollinated crop flowers just as efficiently as honey bees. Even more surprising was the finding that a range of fly species were providing crop pollination. Fly species included hoverflies, whose larvae also attack aphids and other soft-bodied insects; bristle flies, which also attack insects such as moth caterpillars; drone flies, march flies, blow flies and soldier flies.

“When it comes to your insect-pollinated crops, the more of these insects you see the better, as they will be assisting with pollination,” Abie says.

Planting to support beneficial insects

Abie says biodiversity plantings can help provide nectar at the right time for the alternative pollinators. While recent studies focused on native plantings, non-natives can provide good functionality too.

It’s important to get the plant mix right in order to help support the full diversity of key pollinators but not encourage pest species.

In 2013, native plantings containing about 30 species were established on three Canterbury arable farms to test whether they supported beneficial insects. Five years later monitoring showed the plantings were very good for supporting diverse wild pollinators and insect pest predators, but not flower-visiting insect pests.

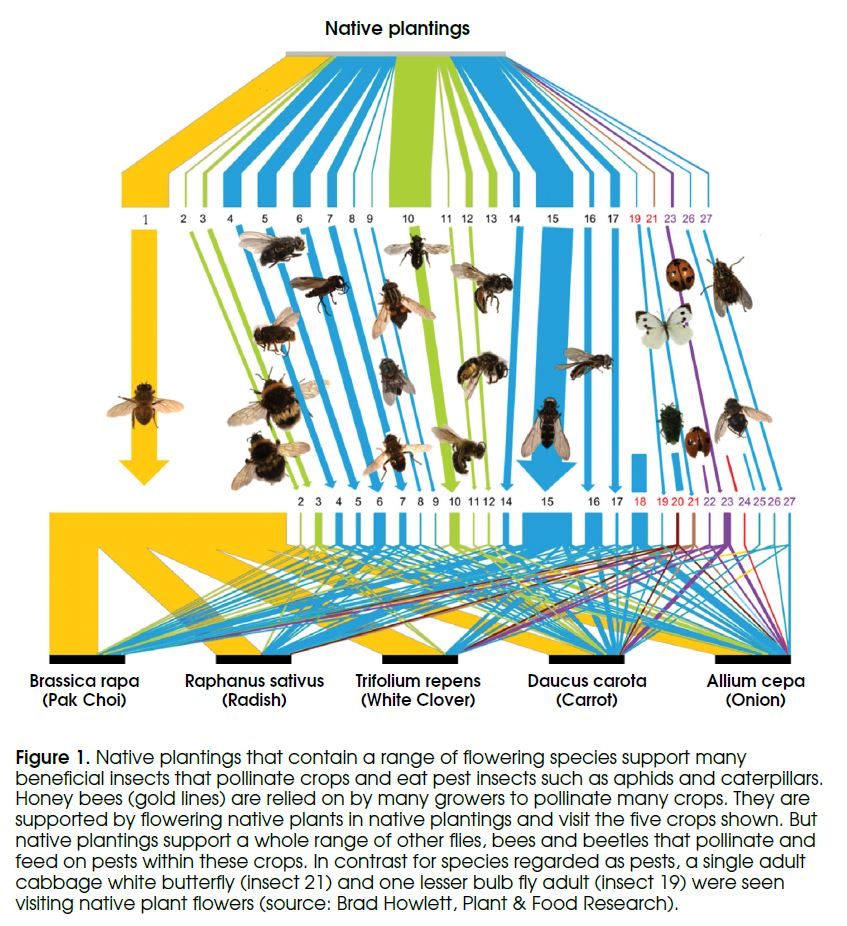

Plant and Food Research mapped the relationship between plants within native plantings and their support of a diverse range of crop pollinating and beneficial insects (Figure 1). The complex network of insects supported by native plants, and their interaction across crops, showed how plantings can generate on-farm insect diversity that will benefit crops.

IPM and beneficial insect populations

A scientific paper looking at parasitic wasps found the number of aphids they can parasitise was hundreds more if they had fed on nectar as opposed to water.

“Having a nectar source available is really important and it’s just thinking about how to get that into the rotation in a sensible way,” Abie says.

It’s important that all the components of IPM are considered as an entire system across the biological, cultural and chemical controls.

“You can do everything by the book in terms of providing that nectar source, but if you are still going in with a routine broad spectrum insecticide then that’s going to unravel all the other good work that’s being done.”

Abie believes farming in the future will likely require the conscious demonstration of informed decisions around inputs such as insecticides, pesticides or fertilisers and that IPM can help with this transition.

“It makes good sense for those farmers who are wanting to be intentional about what they are using and when, and it makes good sense if these beneficials are doing the work for free.